© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

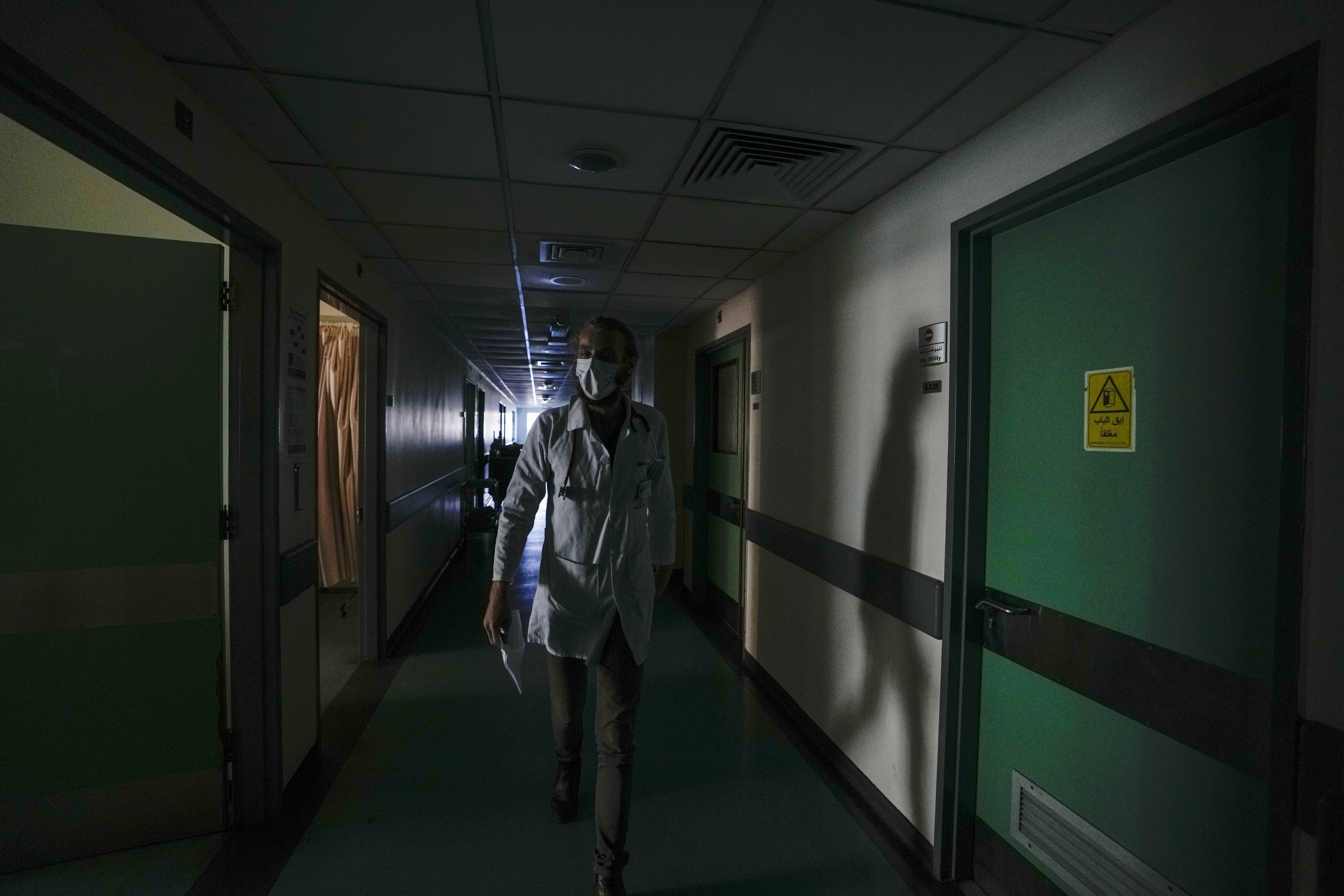

Drenched in sweat, doctors check patients lying on stretchers in the reception area of Lebanon’s largest public hospital. Air conditioners are turned off, except in operating rooms and storage units, to save on fuel. Medics scramble to find alternatives to saline solutions after the hospital ran out. The shortages are overwhelming, the medical staff, exhausted. And with a new surge in coronavirus cases, Lebanon’s hospitals are at a breaking point.

The country's health sector is a casualty of the multiple crises that have plunged Lebanon into a downward spiral – a financial and economic meltdown, compounded by a complete failure of the government, runaway corruption and a pandemic that isn’t going away.

The collapse is all the more dramatic since only a few years ago, Lebanon was a leader in medical care in the Arab world. The region's rich and famous came to this small Mideast nation of 6 million for everything, from major hospital procedures to plastic surgeries.

Ghaidaa al-Saddik, a second-year resident, had just returned from a week off after an exhausting year. Back on duty for a week, she has already intubated two critical patients in the emergency room, both in their 30s. She struggles to admit new patients, knowing how short on supplies the hospital is, scared to be blamed for mistakes and questioning if she is doing her best.

Many patients are asked to bring their own medicines, such as steroids. Others are discharged too soon – often to homes where power outages last for days. "You feel like you are trapped,” said al-Saddik.

The 28-year-old spends more nights in the staff dorms studying because, at home, she has no electricity. She moved to an apartment closer to the hospital that she shares with two other people to save on rent and transportation.

With the collapse of Lebanon's currency amid the crisis, her salary has lost nearly 90% of its value. With fewer and fewer residents, she must now do the rounds for about 30 patients, instead of 10. Her mentor, a senior virologist, has left Lebanon – one of many in a brain drain of medical professionals. "I want to help my people," she said. "But at the same time, what about me being a better doctor?"

The Rafik Hariri University Hospital is Lebanon’s largest public hospital and the country's No. 1 for the treatment of coronavirus patients. Lebanon has so far registered nearly 590,000 infections and over 8,000 deaths.

The hospital, which depended on the state power company, had to start relying on generators for at least 12 hours a day. Since last Monday, the generators have been the only source of power, running non-stop.

Most of the hospital's diesel, sold at the black market at five times the official price, is either donated by political parties or international aid groups. To save on fuel, some rooms run only electrical fans in the sweltering summer heat. Not all hospital elevators are working. Bed capacity has been downsized by about 15% and the ER admits only life-threatening cases.

It is a perpetual crisis that has left the hospital always on the brink, says its director, Firas Abiad. There are "shortages of almost everything.” Every day, he struggles to secure more fuel – the hospital has a maximum two-day supply at any time.

Shelves are thin on medicines, including for cancer patients and dialysis. A new aid shipment of blood serum will last just a few days. "We can hardly get by,” said Jihad Bikai, head of the ER. He recently had to send a critical patient to another hospital because he no longer has a vascular surgeon on staff.

Lebanon’s financial crisis, rooted in years of corruption and mismanagement, spilled out into the streets in late 2019, with antigovernment protests and demands for accountability. Political leaders have since failed to agree on a recovery program or even a new government – leaving the previous one in perpetual but stumped caretaker role.

The World Bank has described the crisis as among the worst in over a century. In just two and a half years, the majority of the population has been plunged into poverty, the national currency is collapsing and foreign reserves have run dry.

Power outages have for years forced dependence on private generators but the crisis took on new dimensions this summer as fuel and diesel became scarce, disrupting the work of hospitals, bakeries, internet providers and many other businesses.

Then last August, a massive explosion at Beirut's port – when hundreds of tons of improperly stored ammonium nitrate ignited – destroyed entire neighborhoods of the city and killed 214 people. Thousands were injured, inundating hospitals, some of which lost members of their staff and were forced to shut down temporarily.

On a recent afternoon at the Rafik Hariri hospital, nurse Mustafa Harqous, 39, tried to ignore the ruckus outside the coronavirus ER: patients with oxygen masks waiting for a bed to free up, families pressing to visit sick relatives, others arguing over out-of-stock drugs. He went about his work in the 25-bed room. Except for a month-old baby, the patients were mostly men in their 30s and 40s.

"Some people understand the shortages are not our fault," he said. "But many don’t." He worries how he will fill up his car for the drive home, an hour and a half away. The government, he said, is "leaving people in the middle of the sea with no rescue boat.”

Reports say at least 2,500 doctors and nurses have left Lebanon this year. At the Rafik Hariri hospital, at least 30% of doctors and more than 10% of nurses left, most recently five in one day. Many private hospitals, which offer 80% of Lebanon’s medical services, are shutting down because of a lack of resources or turning away patients who can’t pay.

Bikai, the 37-year-old ER chief, was offered a job in a neighboring country. His salary is barely enough to cover his son’s dentist's bills. His wife, also a doctor, works by his side in the ER. "There is a moment, when you are pushing hard to get over a mountain, and you get to a place, you can’t move," he said. "I worry we'll get to that.” Abiad, the hospital director, struggles to remain positive for his staff. "Our country is disintegrating in front of our eyes," he said. "The most difficult part is ... we can’t seem to be able to find a way to stop this deterioration.”