© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

When the plane touched down at Diyarbakır Airport, the first thing that hit me was that I had chosen the wrong day to come and visit the heart of southeast Anatolia. Black clouds were hanging over the city like a bad omen while the rain was pouring down hard on us.

But I was determined that nothing would stop me from discovering the ancient city of Diyarbakır, not even the lightning bolts of Zeus.

Since I had very limited time in the city, I certainly did not want to lose any time so I hopped into the car to meet my very kind and extremely well-versed guide, Mr. Abbas. While I was making my way to the heart of the city, I was nothing but shocked: I knew Diyarbakır is one of the most crowded cities in Turkey but I did not know how quickly the city was growing!

On my way to the Old City, both sides of the road were practically "invaded" by new residential buildings that were as tall as they could be; almost all of them were inhabited.

Heading toward İçkale

While I was recording the rapid development in the New City in my mind, I found myself inside the Diyarbakır City Walls, which have been standing tall since the time of the Romans. Mr. Abbas led me to İçkale (or "inner fortress" in English) through the Saray Kapı (Palace Gate) and told me that the site is actually one of the first settlements in Diyarbakır's history.

Being on trade routes throughout history and founded in fertile lands, Diyarbakır, also known as Amida and Amed in ancient times, has always been an attraction for civilizations.

Throughout its 12,500 years of history, the city was home to settlers from the stone age to the Neolithic times which can be seen at the Amina Tumulus that is also located in İçkale.

İçkale is, in fact, a microcosm of Diyarbakır's journey through time. Apart from the tumulus which also bears the remains of the great palace of the Anatolian beylik of the Artuqids, the site is home to buildings dating back to pre-historic settlers from the Romans to the Seljuks and the Ottomans.

The St. George Church is located in the northeastern part of İçkale and although archaeologists can't exactly pinpoint its original construction time, it is believed that it dates back to the A.D. 2 or 3. My guide informed me that the building was originally a temple where people worshiped the sun but when the Christians came to these lands, they turned the building into a church. When the Artuqids came to Diyarbakır, they made a few adjustments to the church and turned it into a public bath. According to some legends, the Artuqids used tools and products developed by Ismail al-Jazari, a Muslim polymath: a scholar, inventor, mechanical engineer, artisan, artist and mathematician, in the palace as well as the bath. Currently, the church has recovered its former identity and serves as an art gallery.

Another outstanding building in İçkale site is the Hazreti Süleyman Mosque and the Tombs of the 27 Companions, built by Nisanoğlu Ebul Kasım in the 12th century. Süleyman, the son of Khalid ibn al-Walid who died capturing the city from the Arabs, is buried here along with his companions. İçkale is home to many other historical buildings that are now used as museums to shed light on the history of the city. Since I had many other places to visit, I made my way to one of the terraces of the museum and took a last look at the Hevsel Gardens, the fertile lands stretching as far as the eye could see near the Tigris River, which has been on UNESCO's World Heritage Sites List since 2015.

Road to the Old City

Then we hit the road again to discover the Old City of Diyarbakır which has culture, history, tradition and modernity all in the same pot.

As I stepped in the Old City one thing struck me right away: The old buildings are extremely well preserved along with the city walls. The buildings and the city walls are made of a strange grey stone that creates a kind of shadow in the area. However, as it turned out, these strange-looking gray stones are actually a blessing to Diyarbakır and its well-preserved historical richness.

The basalt stone actually comes from lava that once a now-dormant volcano sprayed. Thanks to this stone, the buildings are more resilient to the destructive effects of time. And the gray stones offer a cooling effect in the summer heat of the city and keep the warmth inside during the harsh winters.

A young woman plays the "erbane," a traditional musical instrument, and sings Kurdish songs.

Built with these basalt stones, the Diyarbakır Walls have been standing tall since 3000 B.C. The city walls, as well as the Diyarbakır Fortress, are also listed in UNESCO's famous World Heritage List and not without good reason: 95 percent of the walls, which were renovated and extended upon the ancient walls built by the Romans, are still protected as they were once since A.D. 349.

Being home to 33 different civilizations throughout history, Diyarbakır's first major established civilization was the Hurrian kingdom of Mitanni. The Hurrians built the first walls and the fortress and when the Romans began to rule the city in A.D. 66, Diyarbakır became one of the most important garrisons of the Roman Empire in Anatolia.

The Roman Emperor Constantius II rebuilt the walls and enlarged it in A.D. 349 and is rumored to have said, "The walls will stand tall until eternity."

Diyarbakır's walls are the tallest walls in the world and considered to be the second most effective defense system after the Great Wall of China. With its turbot-like shape, the walls not only protect the city form invasions coming from the outside but also enable the city to flourish inside the walls with a sense of security.

Inside the Old City, our first stop was the Ulu Cami (Grand Mosque), the first ever mosque in Anatolia. When Islam's armies captured the city, there was only one large place of worship, the Mar-Toma Church, which belonged to the city's Christians; for 11 months, both Muslims and Christians used the same building to worship, sometimes side by side. However, after almost a year, the Muslims built a mosque which later fell into victim to the passing of time. Yet, in 1091 Seljuk Sultan Malik Shah directed the local governor to rebuild a mosque on the site. Completed in 1092, the mosque is similar to, and heavily influenced by, the Umayyad Great Mosque in Damascus.

In time, each ruler of the city added a little something to the mosque which made it eventually the greatest mosque in Anatolia. The facade of the mosque is typical, like the other buildings of the Old City but the white columns and the ornamented white walls added to the building by the Umayyads gives it a sense of mysticism.

Right next to the northern walls of the mosque is where Mesudiye Madrasah stands tall. The madrasah is the first madrasah to be built in Diyarbakır and it is said that it began to be built in the time of the Artuqids in the 12th century and was finished in the 13th century. The madrasah was one of the most enlightened Islamic academies in the region offering classes from botany to astronomy, medicine and literature.

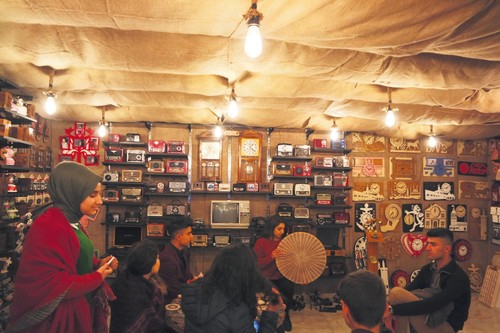

Feeling dizzy by the mystical aura of the Grand Mosque of Diyarbakır, we headed to the Ahmet Arif Literature Museum Library and Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı Museum. Apart from its historical richness, the city is also famous for its literary heritage being home to a few of the most celebrated literary figures of Turkey. Both Ahmet Arif's and Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı's literary genius is celebrated in these museums with events such as poetry readings, music recitals and plays. Tarancı's museum is actually inside his childhood home where he also produced his best works. The museums feature their personal belongings as well as the items that reflect the cultural scene of Diyarbakır.

End of Journey

After we refueled, we made a quick stop at the Deliller Han, which now serves as a five-star hotel. The inn is so large that it did not shock me to hear that Ottoman Sultan Murat IV stayed there on his way to the Bagdad Campaign in the 17th century.

The historic Ongözlü (Ten Arches) Bridge over the Tigris River is an important cultural symbol of Diyarbakır.

Making our way through the narrow streets of the Old City, we came across the Dört Ayaklı Minare (Four-legged Minaret) which is one of the finest pieces of craftsmanship that you can see in Diyarbakır. Built by the Aq Qoyunlus, the minaret is actually more famous than its mosque, Sheikh Mutahhar, due to its strange structure. Unlike normal minarets, this minaret is not physically attached to the mosque but is built on four columns outside the mosque building.

As the sun was going down, we hopped into the car once again and headed to the Ongözlü (Ten Arches) Bridge outside the city walls. Built over the Tigris River, the original bridge is almost as old as the city. According to some archaeologists, it was built in antiquity, in A.D. 515, and restored by the Umayyads two centuries later. It is said that it was destroyed by the Romans once again and rebuilt by the Seljuks in the 11th century. The bridge is 18 meters long and 8 meters in width and a dominating sight over the Tigris. After a long day, I found my hotel and went over my day. I was certainly mesmerized, trying to soak in every bit of information my guide offered me and every little detail on the buildings and in the streets. However, I had to leave out so many places that I regretted I had only given one day to sightseeing in Diyarbakır. Learn from my mistake: Make sure to spare at least two or more days to discover Diyarbakır and get to know its warm-hearted and hospitable people.