© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

Pakistan can be categorized in several ways, like being the sixth-highest populated country and a leading cricketing nation as well as having been home to several ancient civilizations.

However, the Muslim-majority South Asian nuclear power, home to over 200 million people, has another feather in its cap, as it is one of the few countries where over 70 official languages, including some that are endangered, are spoken.

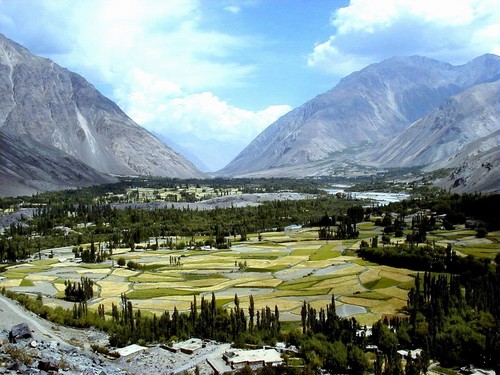

The country's scenic, northern Gilgit-Baltistan region, which borders China and Afghanistan, is alone home to 30 languages with Indic, Indo-Iranian, and Sino-Tibetan roots.

According to Dr. Tafseer Ahmed, a professor at the Center for Language Computing at Mohammad Ali Jinnah University in Karachi, 65 out of the 75 languages spoken in Pakistan are regional, whereas seven languages, including Urdu – the national language – and English are used as official languages in four provinces, Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan.

"Pakistan is one of the countries, which embodies an amazing linguistic diversity. But the alarming thing is that several languages are endangered, dying or already dead," Ahmed told Anadolu Agency (AA).

He said the two old languages - one from the 5,000-old civilization in Mohenjo-daro (Mound of Dead) and the other Domaaki, spoken in Gilgit Baltistan - are believed to be dead by the linguistic experts.

Apart from that, he added, at least eight languages - Badeshi, Torwali, Dameli, Gawar-Bati, Ushojo, Yidgha, Khowar, and Ormuri - which altogether are spoken by less than 100,000 people in Gilgit-Baltistan and parts of northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provinces.

Some 17 languages, including Shina, and Balti are listed as developing languages.

Dr. Rauf Parekh, a Karachi-based linguist sees the situation similarly.

"Not only are the languages declared endangered struggling for their survival, many other languages, which are still not in that category, may meet the same fate in years to come if immediate steps are not taken," Parekh told AA.

For instance, he added, Dameli, an Indo-Aryan language, is currently spoken by nearly 5,000 people in the southwestern parts of the touristy Chital Valley, where 12 other languages are also spoken.

Similarly, Parekh further said, Gawar Bati, and Ushojo – both Indo-Aryan languages – are spoken by less than 15,000 people in parts of Chitral and Kunar province in Afghanistan, and the Swat Valley of Pakistan.

Shina and Balti might be placed on the list of endangered languages as the number of speakers has been dwindling in addition to the lack of documentation and other records, he said.

The last effort in this regard, he recalled, was a decade ago when a Torwali-Urdu dictionary was published.

"This kind of step will at least keep the endangered languages alive, at least in books. Otherwise, they will be wiped out like hundreds of other languages around the globe in years to come," he said.

Globalization

Some linguists describe globalization as a major threat to small languages and cultures.

"Globalization is eating small languages," Parekh said. "The younger generation is drifting toward dominant languages to get education and jobs.

In cities, more and more youths are learning English, while in remote regions, they prefer other dominant regional languages like Pashto or Balochi."

Agreeing with Parekh, Ahmed said: "The survival of small languages has a direct connection with the economy. When a Torwali- or Badeshi-speaking youth has to be fluent in English or Urdu, or at least in a dominant regional language for education and employment, their attention for their mother tongue will automatically reduce."

Migration has been another factor that has reduced the room for small languages.

"Millions have migrated from remote regions from north, northwest and southwest to big cities like Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad, where the general medium of conversation is Urdu, English, Sindhi or Punjabi. Their kids are born and raised in these cities and are ultimately left with no knowledge of their mother tongue," he said.

Linguistic politics

Language plays a pivotal role in the country's politics not only to secure votes but more so to share in resources, according to Parekh. "If not dominant, I would say language plays an important role in the game of politics in Pakistan. Apart from a few national-level political and religious parties, most political parties are actually toeing the line on linguistic politics," he said.

He was referring to even mainstream political parties like the ruling Pakistan Muslim League, led by Punjabi leader Nawaz Sharif, which has strong roots only in Punjab, the country's largest and most populous province, and Hindko-speaking parts of northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

The main opposition left-wing Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), led by a Sindhi leader, former President Asif Zardari, could manage to form a government in southern Sindh province only. Similarly, Pashtun-, Baloch- and Urdu-speaking Mohajirs (migrants) get votes only from their dominated areas in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Balochistan and Karachi- the country's commercial capital- respectively.

"The ironic part of the story is that every community bloats its figures to get a big share of national resources, including jobs. That's why it is very hard to figure out the exact number of their members," Parekh said.

According to official figures, Punjabi is the most widely spoken language in Pakistan, at 45 percent, followed by Pashto at 15 percent, and Sindhi at 14 percent. Other major languages are Balochi, Hindko, Brahui and Kashmiri.

Parekh and Ahmed, however, do not agree with the official statistics placing Siraiki, which is spoken in all four provinces, as the second-most widely spoken language after Punjabi.