© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

Most nationally written literary works have abandoned their oral traditions as peripheral folklore. The differentiation between literature and folklore, though employed in the modern era, is generally understood as a primordial rule of literary creation. Many authors still prefer to use folkloric and mythic narratives in poetry and fiction; however, these are considered only as raw material for creative writing, which is the essence of literature. Consequently, literary history has erased folklore from its canon.

The case of Kyrgyz literature does not comply with the aforementioned supposition. On the one hand, the written culture of Kyrgyzstan began only a century ago; and on the other hand, the oral tradition is still lively among Kyrgyz audiences. This has driven Kyrgyz writers to compromise their modern style to the aesthetics of the folkloric background. The imagery of modern Kyrgyz authors particularly is borrowed from the folk tales and oral poetry of their homeland.

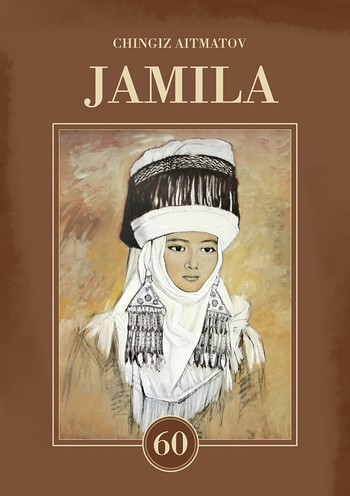

"Jamila," the story of an impossible love becoming possible by the courageous move of a country girl, is one of the most famous books by Aitmatov.

Chingiz Aitmatov, among his fellow Kyrgyz authors, is outstanding thanks to the beauty of the nostalgic country he portrays in his stories and novels and his magical realist style. Aitmatov, who wrote in both Russian and Kyrgyz bridging folklore of the latter to the modern literature of the former, is one of the most celebrated fiction writers today, his books being translated into more than 150 languages.

Early life

Aitmatov was born on Dec. 12, 1928 in Sheker, in the Talas region of Kyrgyzstan, a landlocked and very mountainous country with a population of 5 million in Central Asia. Kyrgyzstan remained a Soviet Republic until its declaration of independence in 1991.

Aitmatov's parents were working as civil servants in Sheker. His father Torekul was a victim of the Stalinist purges. He was charged with bourgeois nationalism, even though he was working for the party as one of the first Kyrgyz communists, and executed in 1938. This tragic incident caused by Soviet violence gave Chingiz a silent and patient character.

His mother, Nagima was a Tartar and a devoted communist, who taught Russian to her son and helped him get interested in Russian literature. Aitmatov learned Kyrgyz traditional folklore from his paternal grandmother, who would take him to traditional events such as festivities and weddings, where the old tales and epics were told and people performed their best to continue the ancestral traditions.

He was educated at the Soviet school in his village. At age 14, he was already working as the assistant of the Soviet secretary in the village. He would work various jobs in later years.

Jamila

Like many other political victims' children, Aitmatov also became a true believer of the regime that killed his father. After studying animal husbandry and agriculture at the Kyrgyz Agricultural Institute in Bishkek, he moved to Moscow to study Russian literature in 1956.

Meanwhile, he had already begun publishing his early works in both Russian and Kyrgyz. His first publication in 1952 was in Russian, namely "The Newspaper Boy" while he published his first Kyrgyz story "The White Rain" in 1954. "Jamila," one of his best pieces, appeared in 1958.

Aitmatov married Keres Shamshibaeva in 1951 and had three sons and a daughter from her. Many years after his divorce from his first wife, Aitmatov married Maria Urmatova in 1981.

"Jamila" is the story of an impossible love becoming possible by the courageous move of a country girl. Jamila, who has a lively and resistant character leaves her husband, a war hero hospitalized for his injuries, for her lover. The short novel is a romantic glimpse of the highlands of Kyrgyzstan with an implication of resistance to traditional society. Though Aitmatov never openly addresses his audience with such political suggestions, the novel has become a novel associated with feminism and modernism.

Aitmatov began writing in the state-run Pravda in 1959, which shows his degree of acceptance by the Soviet regime, which controlled cultural life as well as economic life in all the Soviet Republics. The brilliant Kyrgyz would be introduced to the world by the Kruschev regime as a sign of the moderate attitude of the Soviet leadership after the harshness of the Stalin years.

The Day Lasts More than a Hundred Years

Chingiz Aitmatov is also famous for his "mankurt" concept, which he invented in one of his masterpieces, "The Day Lasts More than a Hundred Years," where he tells the tragedy of a man who is squeezed between Soviet modernism and the traditions of his fellow people. At the end, the Soviets win over the traditions but the individual is not content with his life. The novel is an interesting science fiction piece with folkloric episodes.

Aitmatov won the Lenin Prize for Literature in 1963 for "The Tales of Mountains and Steppes" and the State Prize in 1968 for his first novel, "Farewell, Gulsary!" In 1978, he was named as a Hero of Socialist Labor.

He was not a political adversary. He showed great loyalty to the Soviets, yet he wrote in the most possibly honest way about the social and moral problems of the Kyrgyz Soviet Republic. Good and bad are not political but personal categories in his novels. The problem is not Soviet cruelty, but the cruelty of a certain Soviet person.

Aitmatov's fame enabled him to step into the film industry. The Soviet regime supported the fame of its international writers for the sake of propaganda and cultural imperialism. This helped Aitmatov become involved with films as a scriptwriter.

Even today, years after Aitmatov's sudden death on June 10, 2008, we don't exactly know whether he was a true communist believer or a Kyrgyz nationalist at heart. What we know is the beauty and eloquence of his writing.

Turkey nominated Aitmatov for the 2008 Nobel Prize for literature, although he is Turkic and not Turkish.

Besides for his literary work, Chingiz Aitmatov was Kyrgyzstan's ambassador for many international institutions including NATO, the EU, UNESCO, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. One of his sons, Askar, was the foreign minister of Kyrgyzstan.