© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

The Islamists of the early Republican era were not a well-organized group of people. Unlike in the Constitutional era, Islamist ideas could not be scattered to the public via free media. This was mainly because there was no free media. Secondly, Islamists did not have a clear political program, where the Kemalist People's Republican Party (CHP) and the liberal Progressive Republican Party (TCF) had such programs.

However, the Kemalist regime could not completely eliminate Islamism. Kemalist reforms aimed directly at Islamic traditions. Additionally, the Law on the Maintenance of Order shut down all of Islamist and other critical publications. Finally, no Islamist party was allowed in the political status quo of Turkey. So, how could Islamism survive in such an atmosphere?

The answer is civil society. The vast majority of non-governmental organizations provided Islamism and Islamists with a social environment where they could continue professing their beliefs and thoughts. In addition to that, the Islamist intellectuals covered their political action under conservatism, which was allowed by law to some extent. They made a latent contract with the Turkish nationalistic right until the end of the 1960s, when the new Islamism emerged.

The conservative figures of the early Republican era are interesting due to their heteroglossia. In other words, their mentality and discourse reflect a coexistence of distinct varieties such as traditionalism, scientism, nationalism, Islamic internationalism, conservatism, liberalism and socialism. Said Nursi, for instance, was fond of science, although he was a madrasa scholar and had no formal science education. Perhaps, the more typical individual was Eşref Edip Fergan, who published "Sebilürreşad" before and after the single-party period with two different teams and ideological directions. While the first "Sebilürreşad" was the center of Ottoman Islamists, the second publication became a propaganda tool of apologetic conservatism.

Early life

Eşref Edip was born in 1881 in Serres (now in Greece). He was first educated in his hometown, where he memorized the Quran. He learned Arabic from the Serres mufti. He worked for the Islamic court for one year before he moved to Istanbul to get more education.

He studied law at Istanbul University, where he attended madrasa lectures as well. Nonetheless, education was not his final aim. He collected and published course notes of the law school professors and sermons of famous Istanbul preachers. These were his first publications.

Publisher of constitutional Islamism

As the 1908 revolution freed the media, Edip began publishing a weekly journal called Sırat-ı Müstakim, (Honest and Aboveboard Path) for which famous Islamist writers such as Ebulula Mardin, Mehmet Akif and Musa Kazım wrote columns and articles. He shared the ownership of Sırat-ı Müstakim with Ebulula Mardin, who left it to Edip and moved to the university.

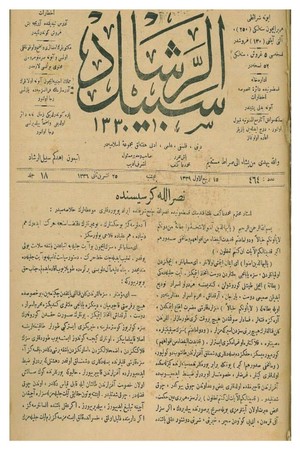

Edip changed the name of his journal to Sebilürreşad (the road taking the person to God) and published it as far and wide as he could. He was a good publisher and organizer since he had no problems with the editor-in-chief, Mehmet Akif the famous poet. Edip and Akif acted together for more than a decade.

Fighting with words

Sebilürreşad was rich in its variety of writing. They published articles about the economy and politics as well as sermons and prayers, yet the most significant pieces in the journal were Akif's poems and political columns where "Sebilürreşad" writers opposed the Committee for Unity and Progress (CUP) government.

Edip was a pragmatic man, so he introduced nationalist views and writers to the audience of the journal as well. Many prominent Turkish nationalists wrote for Sebilürreşad, although they did not share the journal's Islamist ideals. Edip knew how to stay within the argument of power. He never stopped criticizing the government, but he always had friends linked with the government he was criticizing. In short, he could get help from the nationalists, too, in order to oppose nationalist rule.

War after war

What labeled Sebilürreşad was that it was always a wartime publication. A few years after its foundation, the Balkan War exploded. Sebilürreşad instantly reacted against the war. They both criticized the government's policies and praised the national struggle against the enemies.

This attitude became more severe during World War I, which led to a one-and-a-half year ban for the journal. The CUP government closed down Sebilürreşad in 1916, and Edip began publishing it again only after the defeat and imprisonment CUP leaders. Sebilürreşad is a good example of Islamist opposition, which can be banned for a while but continues silently in people's hearts.

When European forces occupied Istanbul, Edip and Akif moved to Anatolia to oppose the occupation and help the national forces. They were welcomed in Balıkesir and Kastamonu. Finally, they arrived in Ankara and began working with Mustafa Kemal and the Grand National Assembly. Sebilürreşad was flexible thanks to its pragmatic owner, so that the opposition journal became a means of national forces propaganda.

However, Edip and Akif continued their Islamist opposition lightly. Even during the War of Independence, Parliament had arguments on certain matters on which the two main groups were struggling against each other. Mustafa Kemal, who would announce his party's single-party rule after the war, led the majority group. The minority group included Islamists together with liberals.

Republic without a public

The Kemalist regime applied hard pressure on all opposition. However, Islamism and Islamists were the main target. The government banned all Islamist publications, closed religious schools, changed the alphabet and charged many people for opposing secularism.

Edip was also sued and charged by a military court; yet, he was released with parole after his journal was banned forever. For the next 23 years, Edip could only publish brochures on religious education for children and some monographs written for Akif and Nursi. This is an example of the Islamist way of survival during oppressive times. If politics were impossible for the Islamists, they would talk on cultural issues implying their opposition against the oppressive rule.

When media was freed again, Edip collected a new team and re-started publishing Sebilürreşad. The second coming of the legendary Islamist journal was not that effective, though Edip continued its publication for about another 18 years.

Edip was sued and released twice thereafter, too. He never stopped arguing against secularism. He died in December 1971. His grave is in the Edirnekapı Cemetery, where Islamist legends such as Akif and Babanzade Ahmet Naim are also buried.