© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

The ghost town of Varosha, known by the island’s Turkish community as Maraş, has historically held a key status in nearly all diplomatic efforts directed at a lasting resolution on the Cyprus question. Long viewed as a bargaining chip in fruitless peace negotiations, Varosha is expected to be on the forefront in a new possible round of talks; however, a former Turkish Cypriot official suggests a break from the long-established set of policies and urges a closer look at the historical status of the land.

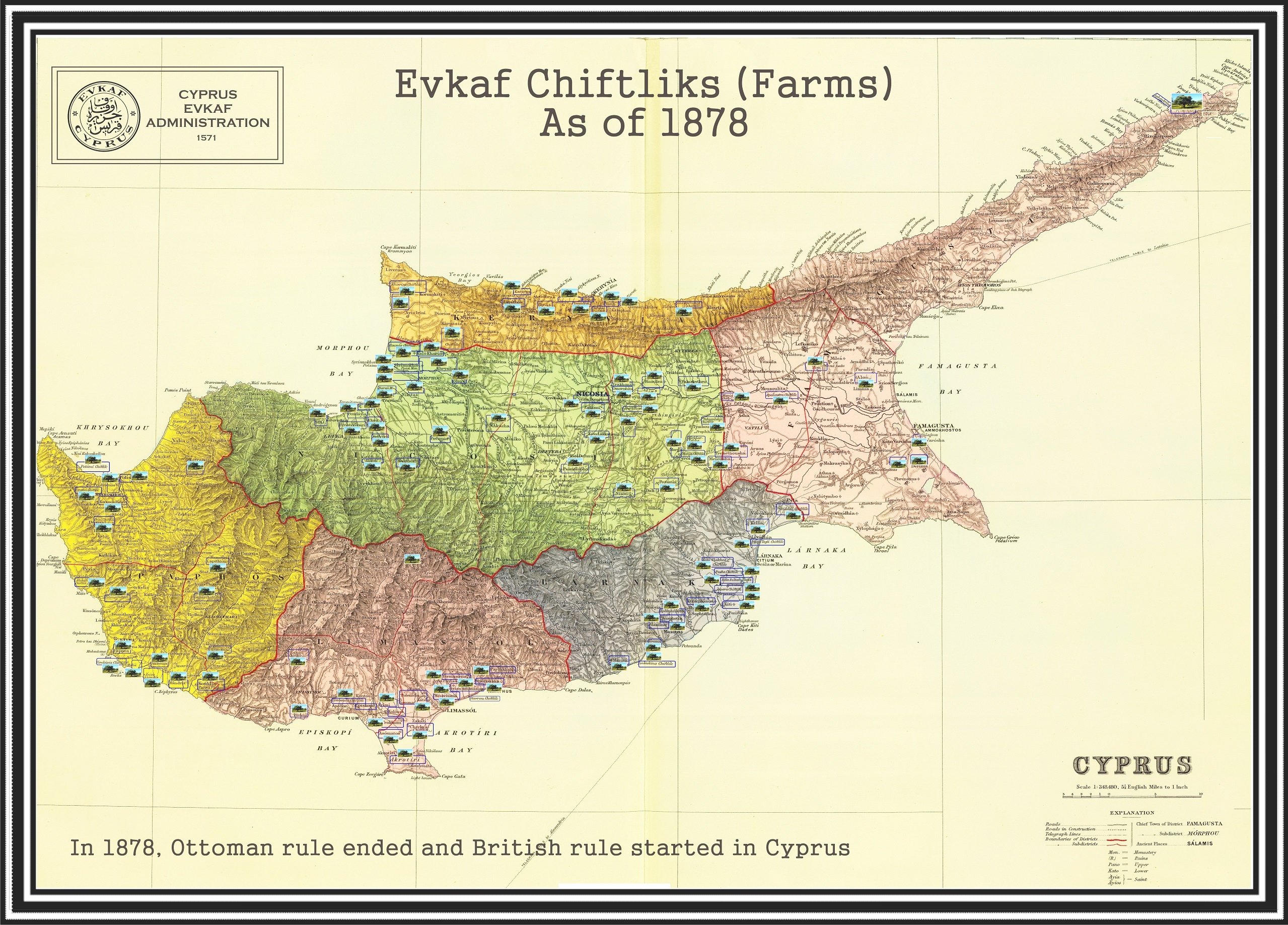

Işılay Arkan, a former board chairman of the Evkaf Foundation that administers Islamic waqf properties and religious facilities on the island, says almost all of the land where Varosha currently stands was endowed by Ottoman administrators and illegally seized during the British colonial rule and ensuing bicommunal Republic of Cyprus (RoC) established in 1960.

The town’s status was again brought to the spotlight on Oct. 8, when the government of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) decided to open beaches and coasts in Varosha to the public, 46 years after it was closed to public access. However, the move was sidelined by the ongoing presidential race in the TRNC. Prime Minister Ersin Tatar, the leading candidate of the first round of elections held on Oct. 11, went on to defeat incumbent Mustafa Akıncı in the second round on Oct. 18 with 51.7% of the votes. Former chief negotiator and Foreign Minister Kudret Özersay, who was the leading proponent of the partial reopening of Varosha, resigned from Tatar’s Cabinet citing the timing of the move, while several other parties supporting a federalist solution on the island also criticized it.

Tatar and Greek Cypriot leader Nicos Anastasiades met for the first time after the elections on Nov. 4 and signaled their willingness to support a new bid for reunification talks launched by United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres. Rivaling hydrocarbon exploration and drilling efforts by Turkey and the TRNC against a Greek, Greek Cypriot, Egyptian and Israeli joint initiative in the making is expected to be the most critical issue presented during the talks, with Varosha remaining as one of the top contentious areas.

“When we look at Maraş, there were waqfs of Abdullah Pasha, Lala Mustafa Pasha and Bilal Agha. All these waqf properties constitute 99.8% of the land in Maraş,” Arkan, a close confidant of the TRNC’s founding President Rauf Denktaş, explains. He argues that the waqf properties in Varosha cannot be returned or sold but can only be rented, given that the amount indebted to the Evkaf Foundation is paid first.

The former official objects to the handling of the issue and points to the need for administering waqf properties with their proper set of rules known as the Ahkam-ül Evkaf (Foundation Rules and Regulations). “As I heard from the latest talks between the Turkish and Greek Cypriot parties, permitting the residence of Greek Cypriots under some conditions is on the agenda, though this decision will not be based on the Ahkam-ül Evkaf but a commission to be formed on the matter,” Arkan says.

“As those who know the region very well, who suffered for this and who fought on the matter, we are saying that the waqf properties are Turkish Cypriot property, that they are subject to Ahkam-ül Evkaf, that these properties cannot be returned even to their former owners. In addition, there is a huge sum by the millions that should have been paid as rent and an agreement can be made after it is paid. Nonetheless, the waqf properties can only be rented and their ownership cannot be transferred,” he continued.

Roots of waqf tradition in Cyprus

Varosha, a suburb of the island’s main port city of Gazimağusa (Famagusta), was the primary resort destination in the Mediterranean, long before the likes of Ibiza or Mykonos came into prominence. Having the best beaches on the island, Varosha was the preferred destination for Hollywood stars. The town once boasted a capacity of 10,000 beds across more than 100 hotels, in addition to posh residences and commercial offices belonging to international companies.

The golden decade of Varosha was, in fact, an anomaly compared with the rest of the island, which witnessed decades of inter-ethnic strife. Following decades of Byzantine rule, the island, with its strategic location and proximity to the Near East, served as a bastion for Catholic crusaders, who later ceded the island to the powerful merchant republic of Venice. Centuries-long Catholic rule ended in 1571, when the Ottoman Empire conquered Cyprus after a long and difficult campaign. Ottomans settled various Turkic tribes on the island, mainly nomads from the Taurus range across the Mediterranean, which formed the backbone of the current Turkish Cypriot community. The Ottoman rule was unchallenged for centuries, mainly due to the “millet system” granting partial autonomy to the Greek Cypriot population and recognition of the Greek Orthodox Church’s authority in civilian and religious affairs. Just like in modern mainland Greece or most of the Balkans, the Turkish presence on the island was mainly confined to the walled cities of Lefkoşa (Nicosia), Famagusta, Larnaca, Limassol, Kyrenia (Girne) and Paphos (Baf), in addition to predominantly Turkish or mixed villages in the south of the Beşparmak (Pendaktylos) Mountain range in the north of the island and scattered villages to the south or southwest of the Troodos Mountains in the south.

During their rule, the Ottomans introduced the Islamic waqf tradition to the island, which endowed various lands and properties to foundations for charitable use to cover the needs of locals and religious and educational institutions. Arkan explains that their calculations show that some 33% to 34% of the land and properties in Cyprus used to be waqf properties.

The modern-day Evkaf Foundation operating in the TRNC is among the few Turkish Cypriot institutions that transcend centuries of political shift on the island. According to an explanatory note by Taner Derviş, a former director-general of the Evkaf Foundation, the institution is administrated in accordance with a special set of rules and principles known as “Ahkamü’l-Evkaf,” forming a substantial part of the legal system in Cyprus starting from 1571. These provisions were also entrenched in Articles 110 (2) and 23 (10) of the Constitution of the bicommunal RoC declared in 1960. The RoC laws also uphold the basic principles of waqf irrevocable, waqf in perpetuity and waqf inalienable. Accordingly, no one can obtain the ownership (title-deed) of any immovable property of the waqfs under any pretext or on any grounds.

British colonial rule reshuffles cards

However, the political upheaval of the last two centuries saw these provisions breached against the rights of the Turkish Cypriot community over and over again, while Greek Cypriots also suffered from the colonial rule. As the Ottoman Empire was disintegrating, Cyprus came under the control of the British in 1878, who long wanted the island for themselves to safeguard their presence in Egypt and trade routes to India, along with fears of possible French or Russian dominance in the region. Athens at the time was more sympathetic toward Russia, the main facilitator of Greek independence, while the royal family was of German descent. Thus the traditional power structure was mainly untouched by the British until 1914 when Britain unilaterally annexed Cyprus in response to the Ottoman Empire joining World War I alongside Central Powers.

Arkan states that from that date on, the British started taking over waqf properties. “At that time, we are seeing that the British are more sympathetic toward Greek Cypriots, who got in contact with the British and demanded 'Enosis,' the incorporation of the island to Greece,” he explained.

“In the 1930s, we are seeing the British illegally allocating the land in Maraş to Greek Cypriots including schools, companies and people. The British appointed a Turkish Cypriot, who was sympathetic toward the colonial rule and was knighted, in 1935 to head the Evkaf Foundation. This person authorized one way or another to allocate the properties to Greek Cypriots, labeling some as his own property and selling to people, leading to irregularities.”

The U.K. currently controls two sovereign bases on the island – Akrotiri in the southern tip of the island and southwest of the major port city of Limassol, and Dhekelia located on the midway between Larnaca and Famagusta. The two base areas, retained by the British in 1959 London and Zurich agreements that established an independent Cyprus, occupy a whopping 259 square kilometers (100 square miles) that include various villages. As land and property rights form the backbone of the ongoing Cyprus question, the status of the bases remains a contentious issue both for Greek and Turkish Cypriots as a symbol of colonial rule.

Greek aspirations fuel tensions

During the 1930s both Ankara and Athens refrained from getting involved in Cypriot affairs due to a thaw in bilateral relations, limited capabilities of both states and the looming threat of war. However, the post-World War II era witnessed the disintegration of colonial empires, including the British Empire. Starting from the early 1950s, the Greek Cypriot community started calling for the island’s unification with Greece. During the period known as the “Cyprus Emergency,” right-wing Greek Cypriots organized under the EOKA militant group started attacking colonial authorities and the Turkish Cypriot community, which formed the Turkish Resistance Organization (TMT) in response. Fearing a Greek annexation, the Turkish Cypriot community was more sympathetic toward the colonial rule, which played into the ethnic and religious divides in Cyprus. This led to more frequent targeting of the Turkish Cypriot community, which was forced to subject themselves to a campaign of terror and were forced to live in enclaves for two decades to come.

The 1950s also saw the rise of a nationalistic elite in the Turkish Cypriot community led by Dr. Fazıl Küçük, as calls for the “taksim” (partition) policy grew louder both on the island and in Turkey. Arkan explains that the British handed over the Evkaf Foundation to Turkish Cypriots in the 1950s after a long struggle. “However, the Turkish Cypriots also did not manage the foundation according to the Ahkam-ül Evkaf. They formed a commission and a community assembly to administer the waqfs,” he says.

There were some claims that the British compensated Turkish Cypriots for the waqf properties. “The U.K. authorities offered Turkish Cypriot community leaders Küçük and Denktaş some 1 million British pounds in exchange for buildings used by the colonial administration, as we understand from some newspaper reports. Some reports claim that the British paid this amount for all waqf properties and some claim that this was paid for the properties in Varosha alone,” Arkan says.

“I discussed this issue with Mr. Denktaş, and this money was taken conditionally. Yes, this amount was given for the buildings that the British were using in exchange for schools, hospitals and hotels to be built, and the Turkish Cypriot community acted in line with this provision,” he adds.

“As time passed, we managed to collect some rent for the properties but not for those that remained in the hands of Greek Cypriots. Not a single penny was paid to the Evkaf Foundation for the properties that were located in Varosha,” Arkan says, adding that the region, formerly dotted with farms and marshes, developed into the primary tourism location in Cyprus and a commercial hub with international companies making significant investments in the region.

Meanwhile, the story for the rest of the island was vastly different. Greek Cypriots unilaterally changed the constitution in 1963 and stripped the island's Turks of their political rights. Nicosia became a permanently divided city in late 1963 with Turkish Cypriots cramped into Turkish neighborhoods, with the Green Line, the U.N. buffer zone currently dividing the entire island, occurring for the first time.

Although Turkey wanted to launch a military intervention in 1964 to end the bloodshed, it was stopped in its tracks by Washington. The infamous letter penned by then-President Lyndon Johnson and addressed to former Turkish Prime Minister Ismet Inonü threatened Ankara with serious repercussions, argued that military equipment provided by the U.S. cannot be used in a military campaign in Cyprus and possibly at war with Greece, and the U.S. would remain neutral in case of Soviet aggression. This was the first example of a series of U.S. indifference toward a national issue of its NATO ally.

Despite the threatening nature of Johnson’s letter, however, the Western world was more sympathetic toward the Turkish cause over atrocities committed by the right-wing EOKA-B militia group and the anti-imperialist nature of Greek Cypriot leadership led by Archbishop Makarios III, the former president of the RoC.

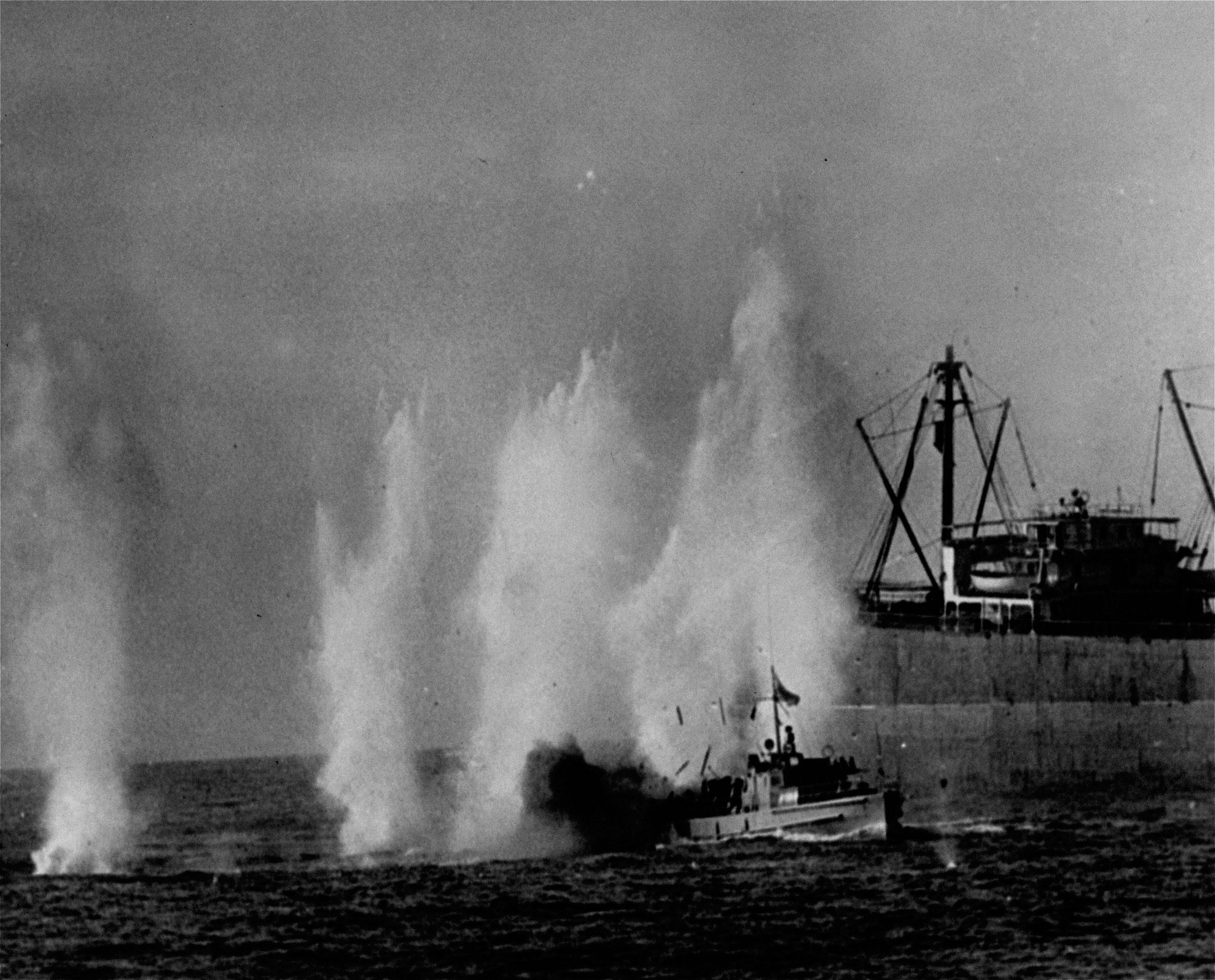

A far-right Greek military junta assuming power in 1967 only made matters worse for Cyprus as Athens started actively supporting militia groups. The events culminated in a far-right coup that deposed Makarios and installed infamous militant Nikos Sampson. This was the final straw for Ankara, which launched a peace operation on July 20, 1974. The first phase of the operation that saw heavy fighting in the north of the island gave Turkish forces a bridgehead in Kyrenia and a connection with the Turkish enclave in Nicosia; however, many Turkish enclaves remained surrounded and under attack by Greek Cypriot forces and militia. The juntas in Athens and Nicosia collapsed, but the ensuing peace talks in Geneva, Switzerland, were fruitless.

The second phase of the operation was launched on Aug. 14 aiming to relieve Turkish enclaves, enlarge territorial control and secure Turkish forces that were deployed in a narrow corridor. While fierce clashes meant a slower advance to the west and south of Nicosia, the Turkish military, backed by mechanized units and tanks, advanced faster on the island’s central Mesaoria Plain, reaching Famagusta and its outskirts in two days. The Turkish Cypriot enclave in the city’s historic fortress area was relieved while Turkish troops stopped just south of Varosha with the British base in Dhekelia marking the end of Turkish advance further west.

Varosha: Frozen micro conflict in the big picture

Unlike other cities or towns in the island's Turkish-controlled north, making up some 40% of the island’s territory, Varosha was closed to the public and was fenced off. The Turkish Cypriot community, now concentrated in the north of the island as the U.N. peacekeeping forces and U.K. troops allowed safe passage from southern enclaves, went on to declare the Turkish Federated State of Cyprus in 1975 and the TRNC in 1983. However, Varosha remained closed under the control of Turkish forces, and no refugees were admitted to resettle in the town. The city is protected by a 1984 United Nations Security Council resolution stating that the empty town can only be resettled by its original inhabitants.

The second phase of the operation turned the tide in the diplomatic field with much of the international community now viewing Turkey as the aggressor. Since 1974, the Turkish Cypriot community and the TRNC are facing a political, economic and cultural embargo with various peace initiatives ending in vain. The furthest advance in peace initiatives came in 2004 with the U.N. Cyprus reunification plan, named after the former Secretary-General Kofi Annan, which foresaw two constituent states forming the United Republic of Cyprus, with the Turkish state controlling 28.5% of the island and with the return of territories in Morphou (Güzelyurt), Karpass Peninsula and west and south of Famagusta including Varosha. The Annan Plan was put to vote both in the TRNC and Greek Cypriot administration, with 65% of Turkish Cypriots voting in favor, while 76% of Greek Cypriots rejected it. Amid international assurances in favor of the plan, Ankara backed the proposal at the time to find a lasting solution to the Cyprus question and clear an important hurdle before its European Union accession process. However, after the Greek Cypriot rejection, the Greek-controlled part of the island, internationally recognized as the RoC, was admitted to the EU in 2004 despite clear promises that this would not be the case and in violation of the EU’s own membership criteria, marking a turning point in the conflict.

At the time, TRNC President Denktaş, who succeeded Küçük in the early 1970s as the Turkish Cypriot community leader, strongly opposed the plan citing unclear assurances to the Turkish Cypriot community, the end of Turkey’s guarantor role and property rights, with Varosha against emerging as a sticking point. With Ankara in favor of the plan, however, the referendum in the TRNC turned into a motion of confidence against Denktaş’s 30-year-long career and unwavering stance in negotiations. The veteran politician announced that he will not run in the 2005 presidential elections, which was carried by former Prime Minister Mehmet Ali Talat, the leader of the pro-unification Republican Turkish Party (CTP) and the “yes” camp in the referendum.

Arkan, who was working closely with Denktaş at the time, recalls their efforts at the time to raise awareness both in Cyprus and in Ankara over the status of Varosha. “When I was on the board of the Evkaf Foundation, the Turkish Peace Forces Command in Cyprus found documents regarding Varosha at a building formerly used as a registrar’s office and handed them to us. These documents were examined by the Evkaf Foundation. I remember a document very well, bearing the name of the waqf, may it be the Abdullah Pasha, Lala Mustafa Pasha or Bilal Agha, the purpose was cited as 'gift,' and the recipient was a Greek Cypriot citizen, or a school or business. This is illegal and unacceptable,” Arkan says.

“In 2003 and 2004, we presented this issue as a report to then-Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. He was very excited and wanted this issue to be examined by a commission, made up of the deputies of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) and the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP). During our presentation, a CHP deputy, a professor whom I do not want to disclose, spoke against our theses, saying 'we are now trying to own these lands that we conquered by the sword in 1571.' Many AK Party and CHP deputies rejected his views, particularly (former diplomat and Turkish foreign ministry undersecretary) Onur Öymen.”

"Following this incident, we were told that this issue will be presented before a European Union commission that includes Turkish members set to convene in Istanbul, and we will be invited to present our theses before that commission,” Arkan said, adding that they were not invited to the meeting and sent their thesis in a DVD, which remains unclear if this was heard or not.

“We applied to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) to seek our rights. It is interesting that even some Turkish lawyers objected to our case. We managed to obtain a ruling from the ECtHR that deemed the application of the Evkaf Foundation is valid and the issue will be examined.”

Arkan says that in the meantime, they asked for Turkey’s help and requested a delegation to come and examine the waqfs and the case of Varosha and to obtain a more realistic picture. “A delegation including experts from Turkey’s Directorate General of Foundations was sent and as a result of their work, it was revealed that the waqf ownership in Varosha is much higher than our previous estimations and these documents were brought to Turkey for further interpretation. We have waited for an answer on this until now.”

“We also carried the information we received from Mr. Erdoğan to Mr. Denktaş, who was accompanied by (late Turkish constitutional law professor Mümtaz) Mr. Soysal and the Turkish ambassador to Lefkoşa (Nicosia) at the time. When I presented our case, I noticed that the esteemed ambassador was not fully informed regarding Varosha. Together with Mr. Denktaş and Mr. Soysal, we explained the historic case of Varosha, the status of properties and that these properties were not subject to a statute of limitation, that these properties belonged to Turkish Cypriots, and the area was closed after Turkey’s peace operation.”

However, the initiatives led by Denktaş – and Arkan – proved unfruitful, and the status quo remains to date. He expresses his frustration with the entire town, with its banks, commercial centers or hotels established by international or Greek Cypriot companies are going to waste. Meanwhile, he explains that the Greek Cypriot side insists on the return of Varosha, causing heated debates.

“Two groups formed in the Turkish Cypriot side, one saying that Varosha cannot be returned and the other arguing that these properties do not belong to the Turkish Cypriot community and should be returned to their former owners, and these debates continue to date. As they continue, the Turkish Cypriot public remains in a confused state regarding the status of Varosha,” Arkan says.