Tunisia's democratic progress is threatened by a recent consolidation of power, raising concerns about a potential return to the bad old days

Post-revolution Tunisia demonstrated a remarkable transition from a one-man rule to a multiparty electoral democracy. However, the country, considered the cradle of the Arab Spring, a series of uprisings against governments that took place in various Muslim countries between 2010 and 2012, seems once again at a crossroads with surprising political measures.

On July 25, 2021, Kais Saied, the president of Tunisia, removed the prime minister, suspended parliament and lifted the immunity for 217 lawmakers of the National Constituent Assembly (NCA). It was followed by the president’s new democratic roadmap, which included a referendum on a new constitution. Despite a low turnout and a boycott by the country’s major political groups, the new constitution was approved in July 2022. It removed many of the checks and balances of the 2014 Constitution and granted absolute powers to the president. One illustration of this new "democratic roadmap" was the president’s unilateral power to appoint the prime minister and the Cabinet. Furthermore, to lend more credibility to the new system, parliamentary elections were held in December 2022 and January 2023, with a record-low voter turnout of only 11%.

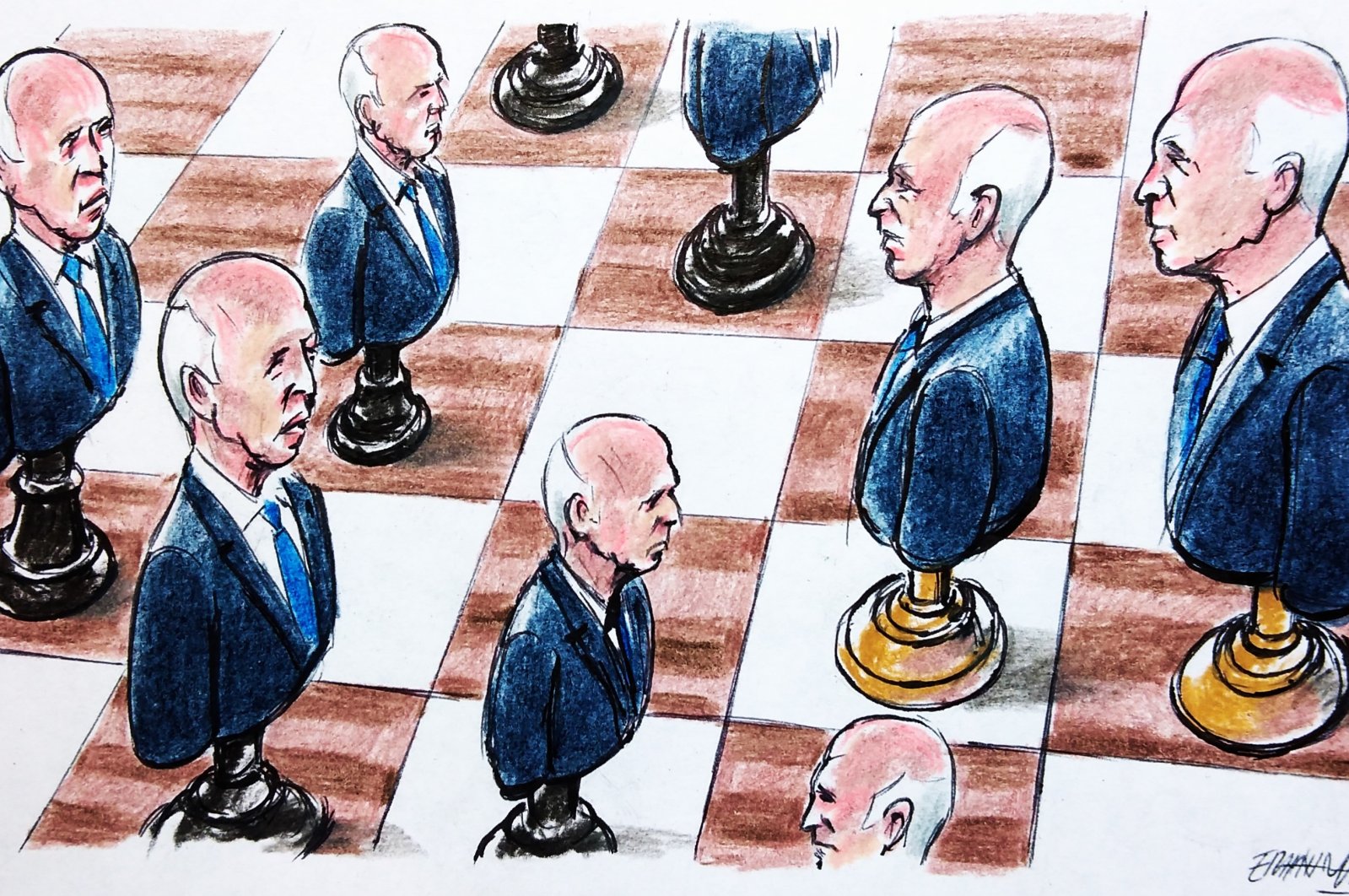

However, since February 2023, a nationwide government crackdown against political opponents, former judges, government officials, trade unionists and journalists has made the situation even more serious and there seems no end to it in the near future. Many believe Tunisia’s democracy is fading because such steps suggest that the country is re-establishing "Ben Ali-style authoritarianism." Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, commonly known as Ben Ali, was the second president of Tunisia from 1987 to 2011. It is in this regard that authors Shadi Hamid and Sharan Grewal argue that Saied’s moves on July 25, 2021, were a "coup d’état." More importantly, neither Freedom House nor the Economist Intelligence Unit classify Tunisia as a free nation or a democracy. In fact, its ranking in Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index has dropped about 50 places since 2021, from 73 to 121.

Was rise a threat?

Saied, a former law professor, won the country’s presidential election in 2019 and enjoyed wide support among the population. Most of the Tunisians hoped that he could improve the economic situation and end corruption. After all, during the 2011 Tunisian Revolution, that led the country to democratization, demonstrators demanded better economic opportunities and social justice. The COVID-19 pandemic worsened the situation and increased dissatisfaction among the Tunisian public. The previous government led by the Ennahda Movement, also known as the Renaissance Party, had miserably failed to deliver their promises. Many Tunisians claim that their failure to control the coronavirus crisis and improve the economy made a significant portion of the population welcome Saied. His 2021 measures were perceived by the public as steps to save Tunisia from its socio-economic crisis. This aligns with Hamid’s argument that his becoming the next president was the desire of the majority of Tunisians if not all. They witnessed the impasse in parliament and the ineffectiveness of coalition governments, and they were ready for a leader who could guarantee them a promising future and that man was Saied.

In 2021, academic researchers Alexandra Domike Blackman and Elizabeth Nugent looked for an explanation for why Saied’s popularity increased dramatically and did Tunisians supported his policies at the expense of democracy. In their study, surprisingly they discovered that less than 15% of Tunisians believed that the president’s actions jeopardized democracy and fundamental rights, while close to 80% supported his efforts to tighten the noose around corrupt politicians.

The emergence and rise of Saied as a strong and populist leader and his ambition to consolidate his authority since July 2021 are amplifying Grewal's prediction, "The most likely form of democratic collapse in Tunisia would be the rise of a popular strongman, as opposed to a military coup or civil war." Through email conversations with the author, many Tunisians such as Mhamdi and Akaichi, who preferred to speak on condition of anonymity, believed that "Concerns arise over the potential escalation of the crisis and the arrests can deepen divisions, erode trust in democratic institutions, and polarize the political landscape.” Despite calls for a return to democratic values, the president feels increasingly emboldened, and his political choices likely signal a shift from "democracy to authoritarianism.”

What’s next?

Thus far, problems remain unsolved. Is it possible to successfully sustain the democratic transition in Tunisia? While economic struggles may make some more inclined to prioritize stability over democratic values, public sentiments and the interplay between political and economic factors can play a role in shaping Tunisia’s political future. Then there are civil society groups and opposition parties who can make a lasting impact, as they did in 2013, in helping Tunisia overcome the crisis.

According to Mhamdi, "They can engage in advocacy, facilitate dialogue, monitor government actions, propose alternative policies and engage with international partners. Collaboration and coordination between these entities are crucial for maximizing their impact in promoting stability, democratic governance and socio-economic development."

In short, while Tunisia seems once again at a crossroads, Mhamdi’s aphorism "Democracy is a non-linear process, with ups and downs. Cautious optimism exists, but vigilance and efforts to safeguard democratic principles are crucial for a sustainable democratic future" evokes optimism, as well as pessimism vis-à-vis democracy in Tunisia.