© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2025

Today, 93% more of the world population lives in countries with a larger aging population compared to 50 years ago. Obviously, almost all countries around the world are aging. This is due to the decline in fertility rate and the increase in life expectancy, both of which are the natural results of economic growth, social development and technological progress. In other words, as a country develops, the country’s population will inevitably age.

So, why is China's aging population a cause of concern? It is simple – China is aging much faster than most Western countries. In 2020, China’s old-age dependency ratio (population aged 65 or more per 100 persons of working age or 15 to 64-year-olds) reached 17. The U.N. predicts that by 2060, this ratio in China will rapidly rise to 53, and thereafter will stagnate between 50 and 60. In the U.K., France, and Germany, this process (old-age dependency ratio increasing from 17 to 53) will take 140, 120, and 90 years, respectively.

In the U.S., the old-age dependency ratio will not even reach 53 before the 22nd century. However, compared to other Asian economies, China's population is aging at a slower pace. It will take only 20 to 30 years for the old-age dependency ratio in Taiwan and South Korea to increase from 17 to 53.

In Japan, the process will also take 40 years, the same as in China, but after that, Japan’s population will continue to age and the old-age dependency ratio will exceed 70. As we have seen, even if population aging may become a problem, its severity may be lower in China than in other Asian economies.

As the population ages, the economy will face a lack of workforce, which in turn will push up labor wages. As wages rise, factories will move to countries where labor is cheaper. This happened in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, and is now sluggishly happening in China again. But most factories continue to stay in China as they can still find enough workers. This is because today’s China still has many workers in the primary sector and they are gradually moving toward cities.

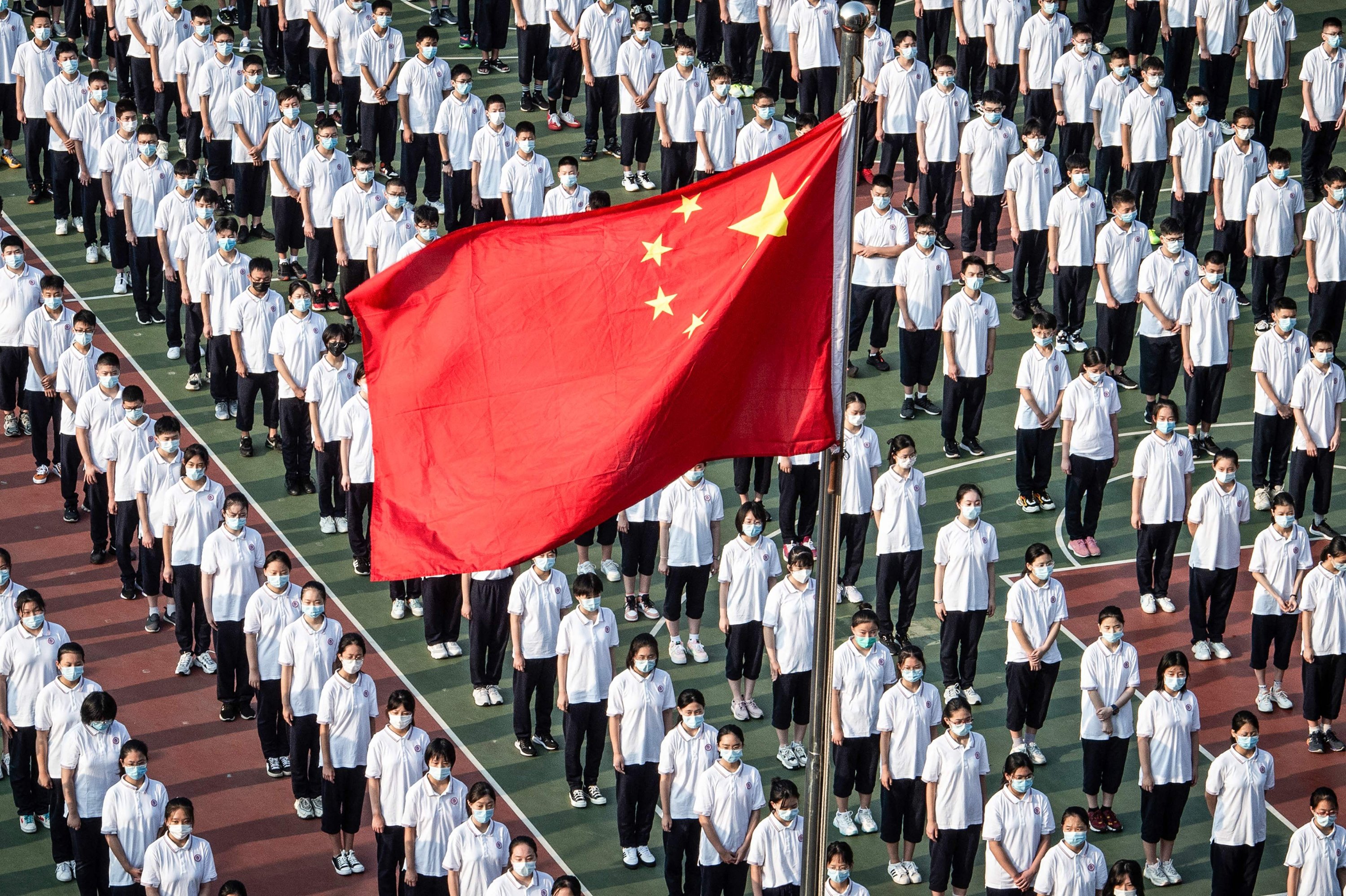

Agricultural employment accounts for a quarter of the total employment in China today, while the numbers in South Korea and Japan were both 13% when they were at similar development levels in 1994 or 1974 respectively. In fact, China's current agricultural employment is comparable to that of Burkina Faso, Egypt, or the Gambia. Due to this domestic immigration, the labor force in the industry and service sectors is growing at a rate of 1.1% per year, while the total labor force in China is declining.

The East Asian economies have the most serious “aging problem” partly because people in that part of the world have a longer life expectancy. This could also be an advantage in future competition, since in East Asia, people older than the working-age are still employable, which may not be the case in other parts of the world. Indeed, the elderly in East Asian economies are the healthiest in the world.

It may be surprising to many that the Chinese people's healthy life expectancy (the average lifespan for a person to live a healthy life, or “HALE”) is 2.5 years longer than the Americans’. However, compared with China's HALE, the retirement age is extremely low. In China, men retire at 60, and women at 55 or 50 years old.

Thus, men in China can expect to enjoy a healthy life of seven years after retirement, and female retirees can expect more than 17 years. The situation in Japan and South Korea is similar. But in Western countries, on average, the good years after retirement and before illness are much shorter – four years for men and six years for women.

This mismatch may be the reason why the pension problem in East Asia is much more prominent than in the West. Adjusting the retirement age in accordance with the ever-increasing life expectancy will alleviate the pension crisis in East Asia to a great extent. And to help increase the productivity of seniors, the Chinese government must also invest more in health care and lifelong education.

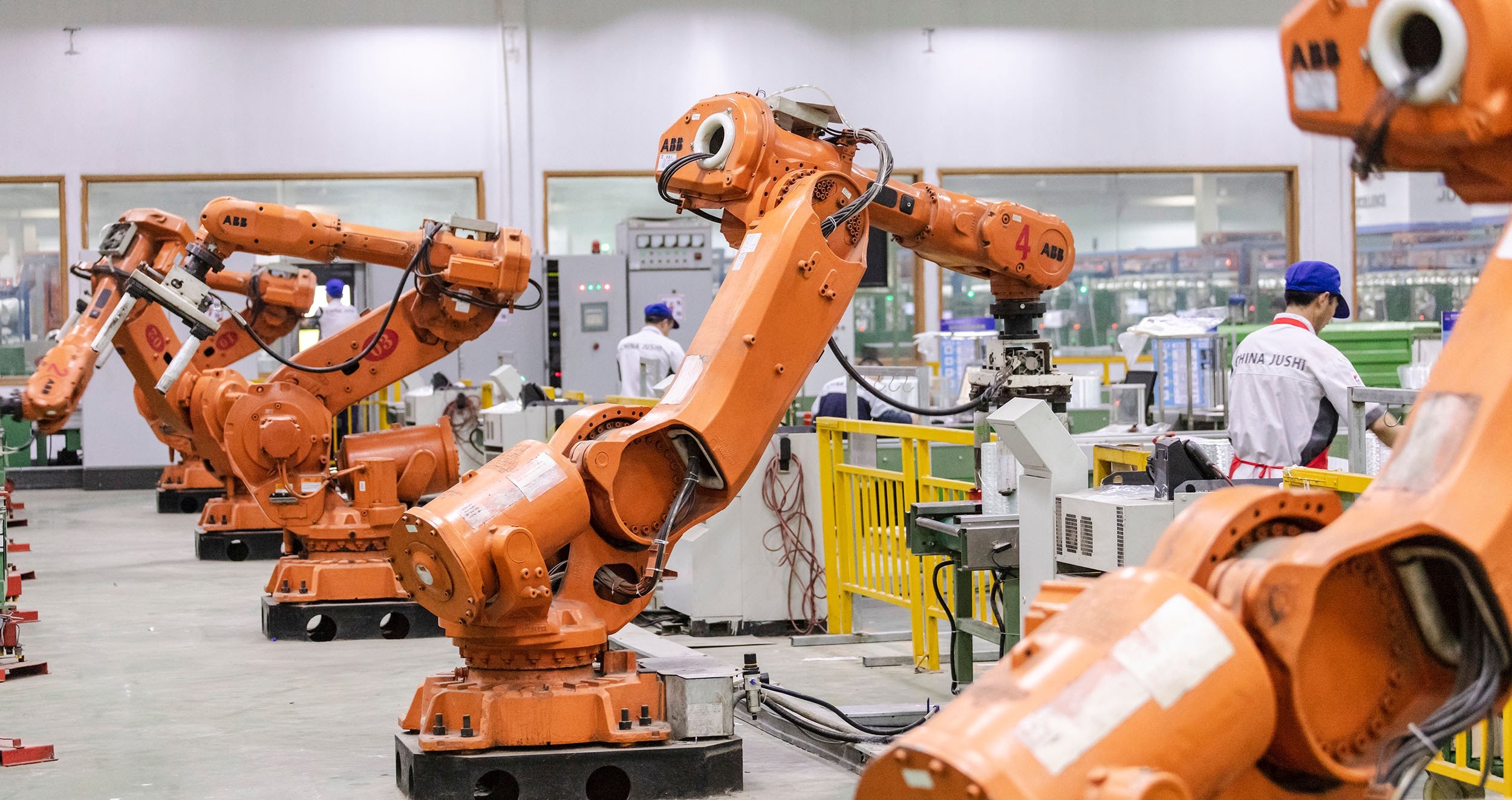

What’s more, humans will not be the only ones working in the future, as robots are rapidly replacing blue-collar workers, and artificial intelligence (AI) white-collar jobs. The density of robot workers (installed industrial robots per 10,000 employees) in China is even higher than that in France and Switzerland, but it is still only a quarter of that in South Korea and half of that in Japan. This also might be a key reason why South Korea has outperformed Japan economically in recent decades. When it comes to replication and production, humans cannot compare to robots or AI systems.

However, humans are more creative, adventurous, compassionate, artistic and entrepreneurial. They are also better at judging, experimenting, exploring and managing. In the future, China will need fewer people in factories and more in laboratories and start-ups. A workforce shortage will be very unlikely when China’s economy has enough robots or AI systems working.

To conclude, population aging is taking place much faster in China than in the West and thus might be a problem for China’s development. In the short term, the huge idle workforce in China’s primary sectors is still the main source of urban labor growth. In the long run, investing more in health care and lifelong education, raising the retirement age and employing more robots and AI systems will probably be the ultimate answer to the aging population problem.