© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

You must have surely heard the pun about ambassadors “lying abroad” on behalf of their countries; this was said in a light vein by Sir Henry Wilson, a 16th-century English diplomat, who joked that an ambassador was “an honest man sent to lie abroad for the good of his country.”

Indeed, Klemens von Metternich (1773-1859), the Austrian Chancellor-statesman, foreign minister, and champion of conservatism who helped form the victorious alliance against Napoleon, thought deviousness was an inherent part of a diplomat’s work abroad.

Let's fast forward to our modern times. Nowadays, diplomats may or may not lie while abroad, but they are closely watched not only by their own countries but also by their host countries as they carry out their diplomatic duties.

Many candidates without any hands-on diplomatic experience or training are given high-profiled ambassadorial assignments – “political appointees,” as they are called in the jargon – because the incumbent leader of a particular country felt obliged to reward for their support, contribution or service to the incumbent leader or because they possess some other special qualifications to deal with a particular country. This practice is common not only in the United States but also in other countries.

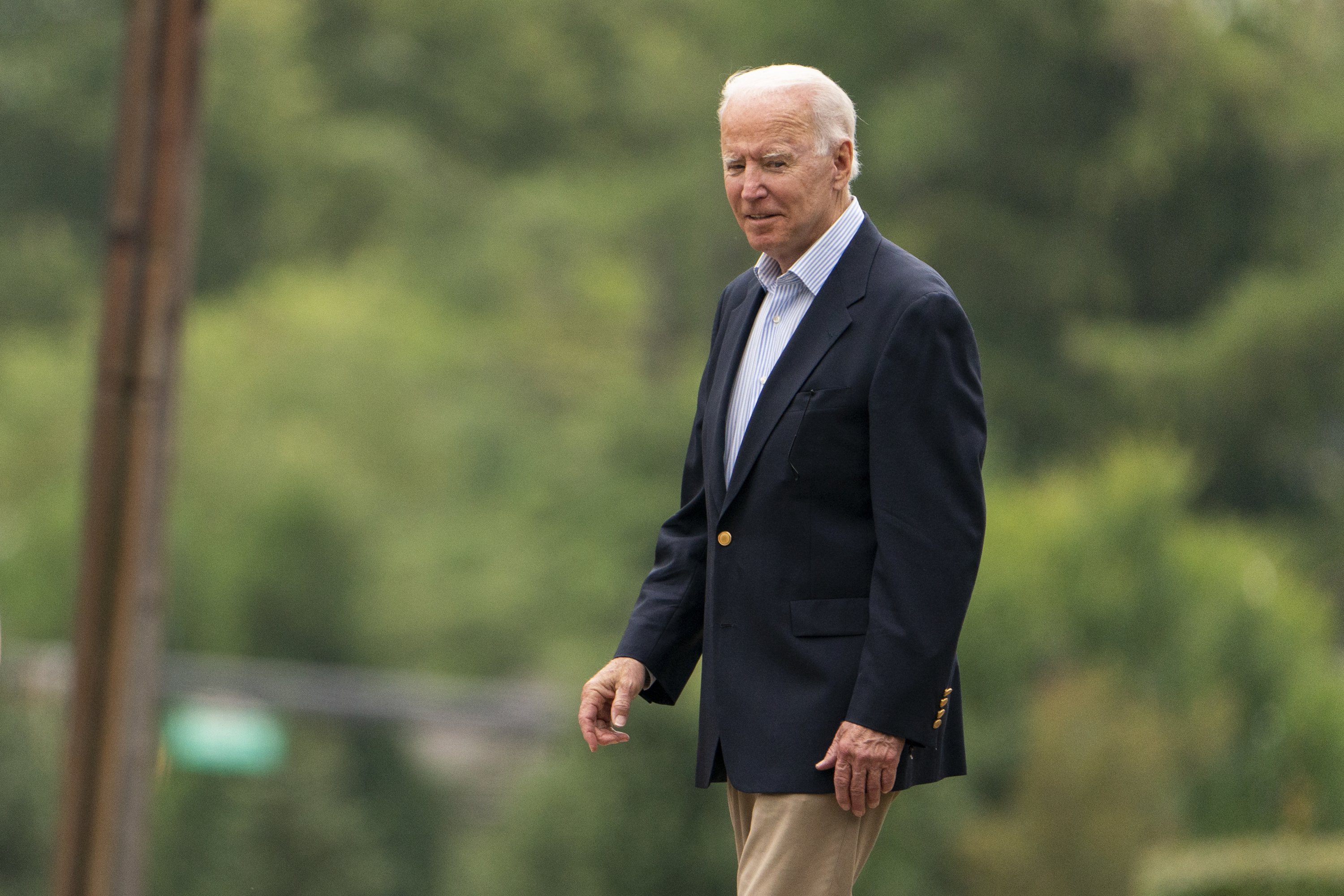

The U.S. has yet to fill in many ambassadorial vacancies since President Joe Biden took over office. However, the grapevine flowing in abundance in diplomatic circles has been churning out names of potential ambassadorial candidates being assigned to a number of countries that are considered important by Washington.

One such candidate is Caroline Kennedy, daughter of former President John F. Kennedy, a friend of Biden, and donor who has already served once before as U.S. ambassador to Japan. Kennedy is tipped to become U.S. ambassador to Australia.

Then there is Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, a strong Biden supporter during the presidential election. Garcetti, future envoy to India, may lack hands-on diplomatic experience but he has considerable exposure to Indian culture and the region’s geopolitics; he has kept himself abreast of India’s political landscape. He has visited India several times, last time as a councilman; as a college student, he spent a year learning Hindi and Urdu and even stayed at the U.S. ambassador’s residence.

In media interviews, Garcetti has been calling India the “world’s largest democracy, soon to be the world’s most populous country and one of the top handful of superpowers in the world.” Garcetti, who holds a master’s degree in international affairs from Columbia University, also studied international relations as a Rhodes scholar at Oxford University and for a short while taught diplomacy and international relations at Occidental College and the University of Southern California.

Another ambassadorial candidate not from the official foreign service cadre is former Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel, who is being assigned to Japan.

Political appointees are seen as “outsiders” and their appointments can demoralize long-serving career diplomats, some of whom have become disenchanted with the “gaping difference between words and deeds,” as one foreign policy think tank representative told me privately.

Biden, he recalled, had stated during the early part of his presidency that his administration was going to elevate career diplomats and empower them. It was thus very frustrating indeed to see plum positions being given to non-career people, particularly at a time when the U.S.’s influence in the world was waning and there was “no way how some high-profiled personalities with little or no exposure to the intricacies of diplomacy and foreign affairs could reverse this trend.”

Indeed, as some critics are saying, the prospective political appointees maintain personal connections or have helped in campaigning or even providing funds for Biden’s election campaign. The choice of the candidates should be made by applying national security criteria to determine their suitability.

The three nominations for Australia, India and Japan were preceded by nominations of Republican senator Jeff Flake for ambassadorial assignment in Turkey, former senator Tom Udall as ambassador to New Zealand and, not to forget, Cindy McCain, the widow of the late Senator John McCain, as ambassador to the United Nation Agency for Food and Agriculture.

The country’s prestigious foreign service is closely monitoring such ambassadorial nominations: the range of such nominations shows that the number of non-career appointments is almost at par with appointments of career diplomats made so far by Biden. There are still many ambassadorial postings to be filled. How many of these posts will be filled in by political appointees or by career diplomats, remains to be seen. Proximity to the president, apparently, lubricates the mechanics that lead to political appointments.

But Biden has also made some “wise choices,” as American officials say, with the appointments of Linda Thomas-Greenfield as U.S. ambassador to the U.N., and Jane Hartley as ambassador to the United Kingdom.

Nevertheless, the overriding criterion for appointments is that a country, usually, picks the best candidates as ambassadors to countries that are rated as most important. China, Russia, Japan and India are of strategic interest, as are European allies such as Germany, the U.K., France and even Turkey.

Reflecting this importance is Biden’s – still unconfirmed – pick of Nicholas Burns, a former undersecretary for political affairs at the Department of State as the next ambassador to China. There is some pressure on the Biden administration to fill in the long-vacant ambassadorial post in Beijing, especially because the new Chinese ambassador to the U.S., Qin Gang, has already taken his post in Washington.

Experts also wonder why it is taking the Biden administration such a long time to fill in new ambassadorial positions when past administrations quickly filled such positions.

Be as it may, making political appointments can strike a note of discord in the foreign service, which can also deter new and promising recruits from joining. This is especially important because, as anyone remotely connected with diplomacy knows, such posts face challenges that can challenge both old hands and newcomers in a different political, economic and cultural foreign environment.

While it can become necessary to appoint an outsider for a particular posting, there should be strong justification for such an appointment, either based on the candidate’s extraordinary qualifications, skills and background; it would be a serious miscalculation to dole out important postings with national security responsibilities to candidates because of the transactional “you-owe-me-one” dictate.

The generation of new entrants to foreign service could also be discouraged by the practice of giving political appointments to those with personal connections. A fair and equitable system, based on merit rather than on personal connections or favors, for giving such important ambassadorial posts would revive interest among young people wanting to join the foreign service.

Talented young people feel comfortable joining the private sector or even other government agencies simply because the industry or other agencies offer better advancement opportunities. It is time to bring about corrections in the practice of allocating positions to political appointees.