© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

While democracy collapses spectacularly in Afghanistan, it starts to die in Tunisia. Tunisia has been known as the start of the Arab Spring for the last decade. In the future, it may also be seen as the place that symbolized its end.

After a day of widespread protest on July 25, President Kais Saied suspended parliament, imposed a curfew and dismissed Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi. This was followed by a purge of senior officials and a month of the former constitutional law professor ruling by decree.

Over the last few days, as the world watched Afghanistan, deputies and judges were placed under house arrest. Whilst Saied has legitimated his actions by invoking Article 80 of the constitution, the legality of his strike against his opponents is extremely contested. However, perhaps the most eye-opening aspect of the last week is the high degree of support enjoyed by the president. Some 87% of the country are reportedly in favor of his dismissing of parliament.

This is a low point for democracy in the Middle East. Two countries, for which the geographical definition of the Middle East is stretched to include both, slide into authoritarianism within the same month.

Democratic systems seem weak before both violence and simple disenchantment. After little more than a decade since the Arab Spring, its poster child and only true emergent democracy seems to have descended into a path towards authoritarianism with the surprising support of its people.

It is also a dispiriting moment for United States and European foreign policy efforts more broadly. While Afghanistan demonstrates the limits of U.S. military capability, Tunisia demonstrates a failure to seize an opportunity.

The Arab Spring was a seminal generation-defining moment for the region and a trigger for grand dreams of reform. A decade on, it is clear that it was a missed chance to create a democratic reality.

While then-President of the European Commission Jose Manuel Barroso spoke in Cairo in 2011 to call for “democracy to bloom” and then-U.S. President Obama promised to “support transitions to democracy” in the same year, both the U.S. and the EU failed to construct a long-term plan for actually realizing and ensuring significant change.

This failure was born out of a lack of understanding of the inherent challenge of the enterprise. Democratic transitions are difficult, prone to ups and downs and are generational endeavors. It is not at all unusual for the pathway to democracy to have multiple false starts and near misses.

In many cases, the seething resentment that generates an uprising is not a useful force for democratization but instead tends to culminate in violence. Three of the countries affected by the Arab Spring are currently experiencing armed conflict. Others have violently returned to degrees of authoritarianism. This should not be altogether unexpected.

The vital truth of significant political change – that there will be great reverses and instability – was often noted by Western policymakers but not truly appreciated. From Libya to Syria, leaders engaged initially and then backed away when faced with fast-moving and complex situations. Western policy oscillates between hand-wringing compromise with authoritarians and launching interventions ill-suited for the quirks of each national context. The fruits of this strategy are made clear by their absence.

Instead, Western foreign policy toward the Middle East should reorient itself toward a persistent and committed engagement to democratization that is explicitly focused on the long-term. Tunisia should not be viewed as a confirmation of prior beliefs of the inevitability of authoritarianism in the region, but as one step backward in an enduring march toward the best outcome for the Middle East and the world: a democratic, prosperous and peaceful state system.

This means two things for Western foreign policy. Internationally and on the state level, leaders must be true to their democratic principles, even when it means momentary instability or difficult relations. This means no cutting corners and buying temporary political gains for long-term maintenance of fragile systems. This effort should be more than just criticizing abuses of human rights but also stepping up to the plate when necessary. The Obama administration’s commitment of $2.2 billion of aid to assist Arab Spring countries – an amount not nearly enough to comprehensively facilitate the process of democratization – exemplified this issue.

Domestically, it means that the West should help encourage strong sentiments of national unity and commitment to democratization in Middle Eastern societies. In the past, efforts have focused on the trappings of democratization, rather than the spirit. Committees, conventions and congresses can be created but must be identified with by the vast majority of citizens if they are to succeed. They need the belief of their people that they will not be hijacked by elites or certain ethnic groups. The dangers of failure are too great.

To this end, a national identity is essential, and it is its absence that so often leads to conflict. In Tunisia, this was sorely lacking. A prescient study found that marginalized cities in the peripheral south had already ceased to identify with the political parties dominated by the coastal elite by last spring. It should be no surprise that the same cities were the first to launch protests by the summer. Any process that does not include this element simply does not have the stamina and goodwill to overcome the inevitable trials and tribulations of democratization.

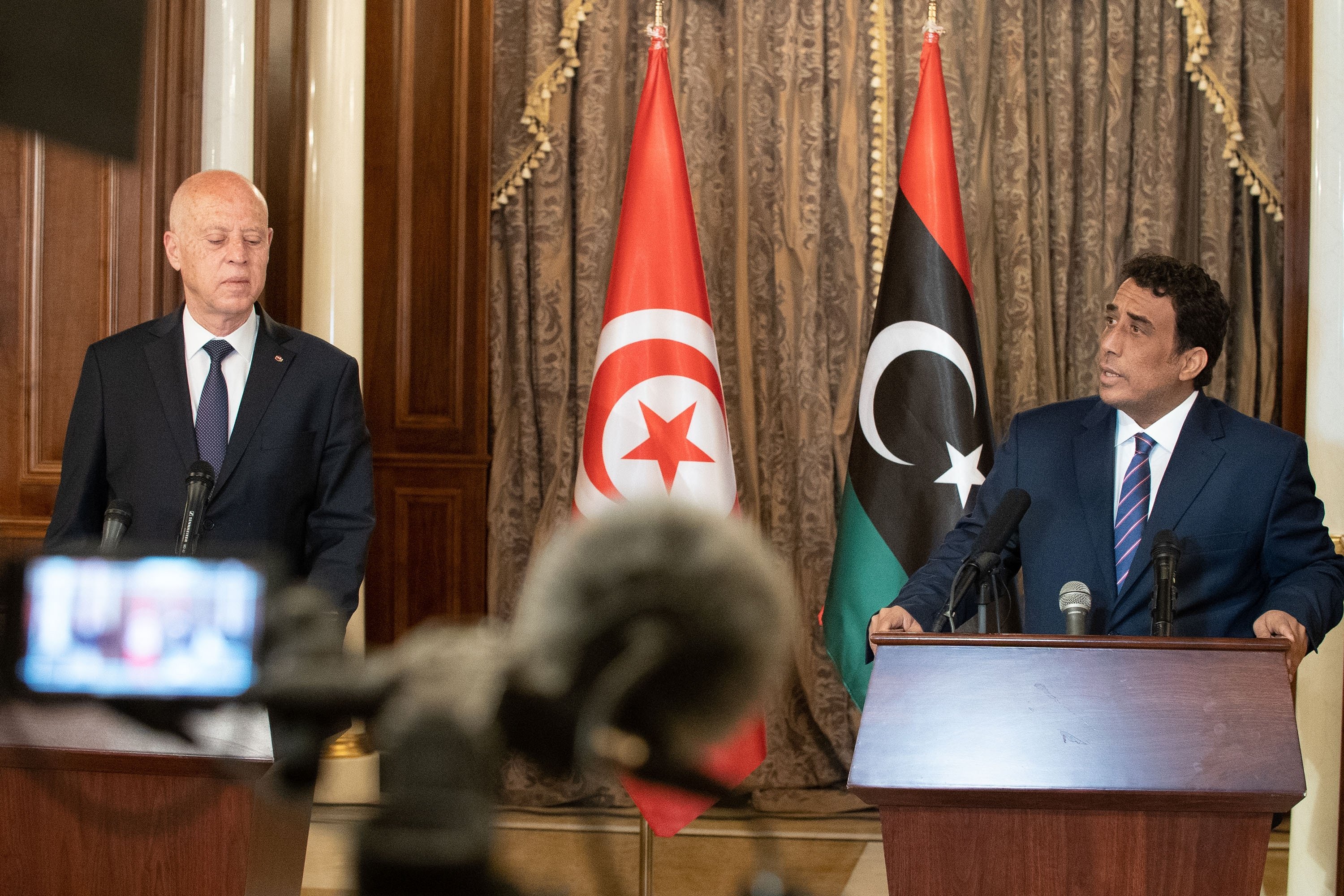

These lessons should be applied rapidly to Libya as perhaps the sole country with the best chance of a true democracy. Libyans already are familiar with the perils of national division as demonstrated by the past decade of conflict. While there is an ongoing internationally led constitutional process mired in haggling, the real solution will be found in using solutions rooted in Libya’s own history and culture to help create a sense of national unity that can handle and resolve bumps in the road. This internationally led constitutional dialogue is not entirely trusted by Libyans nor does it have significant buy in from key actors. It therefore cannot be a true substitute for the national unity essential for democracy.

Western actors should instead search for and support a solution that emphasizes such unity. They need not look beyond the 1951 Constitution, which in the Libyan case, has demonstrated its ability to provide a heavily divided society with an essential sense of national identity. What form the 1951 Constitutional template takes can and should be discussed by local stakeholders, however using authentically Libyan solutions is a much-needed starting point. If not, even if the constitution is agreed and elections are held, there is no guarantee that the first loser of a democratic contest will simply not pick up guns again, derailing years of progress.

After a worrying month for supporters of Middle Eastern democracy, key truths must be remembered. It remains in the regional and global interests of the West to encourage democracy in the Middle East. It is also still the preference of the vast majority of Middle Eastern populations. However, a change in approach is required with an emphasis on an unwavering commitment to democracy but an understanding that it is a delicate long-term process.