© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2025

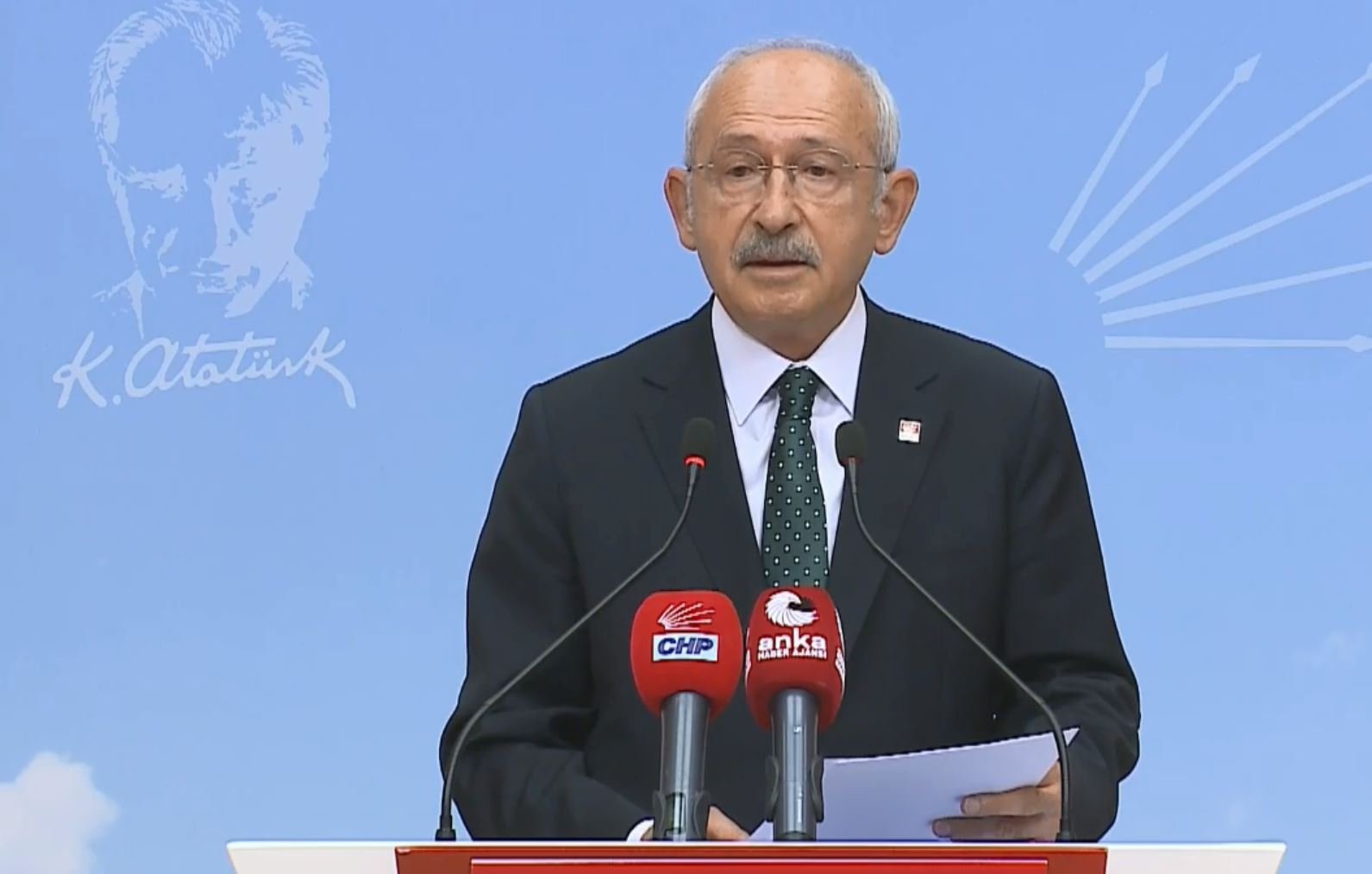

The opposition keeps looking for a presidential candidate for Turkey’s 2023 elections. Main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, who has signaled his intention to run, notably called on the mayors of Istanbul and Ankara to run for second terms.

That statement was reportedly motivated by projections that the country's ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) would claim either municipality if the current mayor were to run for president. Even though it is doubtful that either of the mayors, who could not make a difference in office, stand a chance, it is an indisputable fact that the AK Party would regain control of those municipalities thanks to its majority in the town councils.

Indeed, Kılıçdaroğlu brought all potential opposition candidates down a peg with his most recent move. Earlier, he had signaled his intention to run after failing to stop Good Party (IP) head Meral Akşener, by publicly opposing the candidacy of party chairs. This time around, Kılıçdaroğlu seems to have finished the job by pushing back against his party’s two mayors.

Yet the opposition still faces the same old dilemma. They are looking for a president that would be compatible with parliamentarianism. Yet they have to win an election under the presidential system. To accomplish that goal, they must bring together political parties with contradicting ideologies.

By contrast, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan won in 2014 and 2018 by advocating a strong presidency. At this point, restoring the parliamentary system is far more difficult than defeating Erdoğan in an election.

Kılıçdaroğlu, who cares deeply about his relations with the IP and the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), came up with a new criterion for the opposition’s potential presidential candidate: Self-control.

In doing so, he described his ideal candidate as “a wise person who won’t be corrupted by the presidency’s extraordinary powers – someone who will transfer that power back to the Parliament and the prime minister without delay.”

It is possible to argue that that definition could make it more likely for non-political candidates or the chairpeople of fringe parties to contest the presidential election. After all, the opposition’s “self-controlled” candidate is supposed to abdicate their mandate as part of a plan to restore the parliamentary system.

The main problem with that approach isn’t just the opposition’s inability to field a self-proclaimed "visionary leader" against Erdoğan – there is the issue of having to transfer power to a broad coalition, comprised of multiple party leaders, upon receiving a popular mandate under the presidential system.

Why does that matter? The country stands to face a serious challenge if the opposition cannot claim enough seats to amend the Constitution – even if the opposition’s presidential candidate were to win. The popularly elected president must, then, either govern under the current system or do the bidding of the leaders of those parties, which endorsed him/her, by not exercising their powers.

Both of those decisions are immensely difficult. If the elected president chooses to exercise their powers, bearing responsibility for the majority’s support, they could be accused of lacking “self-control.” Their actions will be criticized as a betrayal of their sponsors’ trust. By contrast, if they were to “transfer” their powers in practice, they will be judged by the performance of a highly fragmented coalition.

In other words, the main opposition leader’s “low-profile” and “self-controlled” presidential candidate is supposed to perform three distinct tasks simultaneously.

First, they will challenge Erdoğan, who will have been running Turkey for 21 years. They will compete with the incumbent in terms of leadership traits, vision and projects.

Secondly, they will hope to secure the electorate’s support by saying that they will abdicate the powers of the “strong presidency.”

Finally, they will both perform well under the presidential system, and facilitate the return to parliamentarianism.

It remains to be seen whether Kılıçdaroğlu can actually find someone to assume all those responsibilities. What we already know, by contrast, is that he successfully weakened all potential candidates from the opposition – thus increasing his own ability to handpick the candidate.

The ball is now in Akşener’s court. I can hardly imagine that the ruling party is remotely bothered by the amount of energy that the opposition keeps wasting on calls for an early election and the debate on the ideal candidate’s profile.