© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

In October 2015, I was interviewed by Sabah's economy service about the possibility of dozens of World War II-era aircraft that may have been dismantled and buried beneath the airfield at the 2nd Air Supply and Maintenance Base in Kayseri. This topic remained in the local, national and international headlines for several weeks. During this time, I suffered the scorn and ridicule dished out by members of certain aviation-related social media groups for reigniting an urban legend for the umpteenth time, and I'm sure to be the laughing-stock of the neighborhood again when they read this.

But we all know that President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan looked squarely into the eyes of the commander of the Turkish Air Force and said, "There are buried aircraft in this country" during a satellite-launching ceremony held in Kayseri held in 2016. When subsequently pressed for a comment on the matter by the press, the commander, whose native town was Kayseri, strongly refuted this claim with a single word, "Hogwash."

Later on, I set up a team called the Focke-Wulf FW-190 Recovery/Recovery Group and appealed first to the president's chief advisory for technology, Davut Kavranoğlu. Nothing clicked. Then, we paid a visit to former President Abdullah Gül with a proposal to exhume these aircraft with the cooperation of his namesake university in Kayseri. Alas, this appeal also fell on deaf ears, and we dropped the matter entirely after I received a trite message six months later from the General Staff, which essentially read between the lines, "What happens in Kayseri, stays in Kayseri."

Turkish pilot Vahdet Gürol made an emergency landing in this FW-190 Aa-3 No. 4137 on Jan. 8, 1945.

Which, if you ask me, seems more than a bit outmoded as the aircraft haven't had any strategic value for the past 70 years, not to mention the fact they would possess some enormous potential to boost the tourism industry in Turkey and particularly, in the central Anatolian region.

To put the situation into better perspective, there no more than a handful of airworthy FW-190s, just one with its original BMW-801 engine and only three original Focke-Wulf A-3 series aircraft on static display in existence on the whole planet. Of the surviving A-3 aircraft, one is in Norway and two are in the U.S. In other words, we are talking about some extremely rare aircraft. So, what's the story behind these Focke-Wulfs in Turkey? Let's take a look back through history.

Turkey's procurement of the FW-190 Aa-3 was the second-to-last link of a chain of events in joint Turkish-German aviation relations, which started prior to World War I with the arrival of German planes and aviators during the Ottoman Empire. It was followed by the foundation of the ill-fated TOMTAŞ factory with the cooperation of Junkers Airplane Factory in Kayseri on Oct. 6, 1926. This facility was to lay the foundation of the Turkish aircraft industry during the early years of the republic.

In accordance with agreements signed in the following years, various German planes were procured and served in the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK), among which were the all-metal Rohrbach Rodra Ro-IIIa seaplane, the Gotha 145A instrument trainer and earlier Focke-Wulf trainers (FW-44A, FW-58-10) and the Heinkel He-111 twin-engine bomber.

Nearly two years into World War II, the two governments signed a nonaggression pact on June 18, 1941. Negotiations were led by Franz von Papen, who had been Germany's chancellor before Adolf Hitler, and who was shuttled off to serve as his nation's ambassador to Turkey between 1939-1944. Credit negotiations were concluded in July of the following year and resulted in a barter deal worth 100 million Reichmarks.

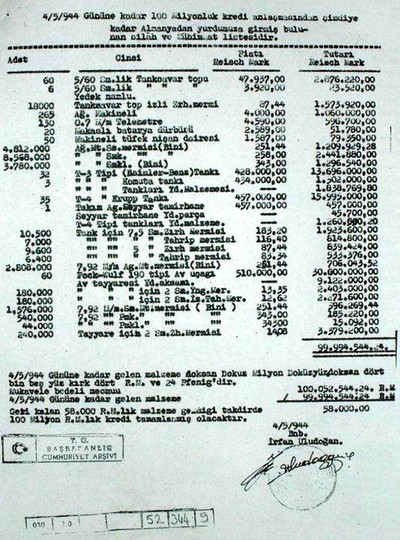

The list of the military equipment Turkey bought from Germany.

War supplies from Berlin

In essence, Germany was to provide war supplies – aircraft, anti-aircraft guns, tanks and spare parts – in exchange for crucial strategic commodities, namely chromium and high-grade iron. Sixty disassembled aircraft were shipped via rail at a unit price of 510,000 Reichmarks, with all the shipping and insurance charges paid by Germany.

Another 12 units were shipped as spare parts, for a total of 72 aircraft. This was equal to about one day's output of around 3,000 aircraft a month; so, it did not constitute a significant number of aircraft for Germany, and the deal was done to keep Turkey friendly with the Axis powers.

A few months before the FW-190 Aa-3 aircraft designated for Turkey were shipped from the plant in Lizenz, Germany, several Turkish Air Force personnel traveled there for a pilot orientation course. The personnel included: Capt. Nuri Ayça, Capt. Burhanettin Gökçü, Capt. Hasan Ayavar, Lt. Turgut Tabu, Lt. Selahattin Yentürk and Lt. Akil Fırat.

Incidentally, I had the privilege of meeting the future father-in-law of Brig. Gen. Lütfü Gündoğdu, Capt. Burhanettin Gökçü, who ended his flying career when he wrecked a Republic P-47 in 1948. All the FW-190 Aa-3 units were delivered to the rail station located on the perimeter of Yeşilköy Airfield between March and August 1943, with the first flight made on June 10, 1943.

The aircraft were assembled and prepared for flight by German specialist personnel, and then were flown to Bursa by the aforementioned Turkish pilots who were trained in Germany, to be deployed alongside Spitfires with the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th Squadrons of the 5th Air Regiment. Pilots assigned to fly the FW-190 were selected from among Hurricane pilots after passing tests on the ground and in the air.

The cockpit of the cramped Focke Wulf FW190 aA3.

While based in Bursa from June 1943 until May 1948, they were also deployed at other locations during this time, namely in Sarıgazi in Istanbul and Merzifon. Turkish Air Force Capt. Tacettin Gökdeniz wrote an article that was published in the August 1954 issue of the Turkish Aeronautical Association's Flying Turk magazine in which he mentioned that 36 Focke-Wulf FW-190's took part in a flight from Bursa to Kayseri in the summer of 1948 and that one of these aircraft made an emergency landing in Eskişehir. Though unsubstantiated, the FW-190 aircraft supposedly deployed with the 4th Air Regiment at Merzifon flew in formation to Kayseri for maintenance in January 1948.

Nicknamed the "Butcher Bird" by its designer Kurt Tank, a total of 20,065 copies of the Fw-190 of all types were manufactured in eight different factories, including Focke-Wulf, Arado, AGO Flugzeugwerke, Fieseler and Dornier, between 1941-45. Nearly 75 years after the end of World War II, it has been determined that only 23 copies of this aircraft survive in museums around the world. There is just one flying example with its original BMW-801 engine, a A-5 model.

The FW-190-Aa3, which was only delivered to Turkey, was equipped with a 14-cylinder BMW 801 D-2 radial engine that was built at the Eisenach plant and rated at 1,700 PS (1,677 hp, 1,250 kW) at take- off. It had a maximum altitude of about 37,000 ft. and a maximum speed of around 640 kilometers per hour. With an improved supercharger and higher compression ratio than its predecessors, the A-3 variant also required higher octane fuel. The Turkish Aa3 variants had the same armaments as the A-1 model: four 7.92 mm synchronized MG 17 machine guns and two 20 mm MG FF cannons. Also, there was no FuG 25 IFF device in the radio equipment.

BMW-801D in Istanbul

As an interesting side note, there is an intact BMW-801D on display at Yıldız Technical University in Beşiktaş, Istanbul. It was brought here from Bursa sometime between 1948-1952, during the tenure of Rector Necdet Eraslan. It can be found inside the entrance of Blok E-2.

The reasons for withdrawing the FW-190 from use were as follows: The German metric system did not comply with the imperial measurement system used on aircraft that came with the U.S. Military Aid package known as the Marshall Plan.

Spare parts were no longer available from Germany, which was defeated in the war.

Chasing a 40-year old dream. 16-year old Stuart Kline posing with a Focke Wulf FW-190 at the Imperial War Museum, Huxford, England, 1979.

The U.S. Army Air Corps sustained many losses from German fighter aircraft, such as the Focke Wulf FW-190 and Messerschmitt Me-109, during World War II, so the Americans most probably insisted on the removal of the German aircraft from the Turkish Air Force.

Though they may have still been airworthy, they had inadequate armaments, with only two machine guns and two 20 mm MG FF cannons. Although they had the proper mounts, these aircraft were not delivered to Turkey with the extended range 300-lt drop tanks, limiting their range to just 835 kilometers.

The real reasons for hiding

Since it was still considered a versatile warplane, it was thought that it could be pressed back into service at a time when the world was rapidly changing during the post-war era, with the onslaught of the Cold War, the foundation of the United Nations, the struggle against communism and the beginning of the Atomic Age. After all, only 15 minutes were needed to assemble the engine and fire it up.

Was there heavy machinery in Turkey at the time to effectively bury the aircraft in Kayseri? Yes, there was.

What we expect to find in Kayseri

The planes, which are believed to number as many as 50 and lie at a depth of about 5 meters, must be meticulously removed in accordance with the technical plans.

In addition to 35 Focke Wulf FW-190-Aa3, there may also be up to 10 Spitfire Mk-Vs and Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawks as well as one Messerschmitt Me-109 buried.

A reference to the Messerschmitt is found in a book entitled "Havacılık Tarihinde Türkler – 3 1939 Yılından 1945 Yılına Kadar."

In an effort to flee from Russian planes in hot pursuit, a German Me-109 fighter plane eventually broke away and landed intact near Zara, Sivas on January 22, 1943. The aircraft was transported to Kayseri, and its pilot was interned in Ankara. Detailed references on all of these points are to be found in the aforementioned book.

The 5th Air Regiment's second squadron of FW-190s stationed in Bursa was deployed at Sarıgazi and was assigned the task of defending Istanbul, the straits and northwestern Anatolia. These aircraft were kept in a constant scramble status. Because there wasn't any radar at the time, these interceptors took off whenever the pilot was informed that enemy aircraft was sighted. A tall wooden tower was built on top of Çamlıca Hill in Istanbul manned with observers who would watch for enemy aircraft. Whenever planes were seen, a stack of hay piled near the wooden tower would be set ablaze, which served the purpose of informing the airfield that enemy aircraft had been spotted. Similar measures were also taken in other regions of the country.

The pilots of the four aircraft on red alert at Sarıgazi Airfield sat in their aircraft, awaiting the signal to take off after batteries were used to kickstart their engines.

There was an incident in which a German He-111 was spotted over the sea, on approach to Sarıgazi. Pilot Haydar Gürsan had his engine started as he led the first of two aircraft to take off, with the other flight leader, pilot İbrahim Tozan, following with a second plane. They ascended to the Heinkel's altitude and took up tactical positions on both sides of the Heinkel. No hostile action was observed on the part of the He-111, which had lowered its landing gear and flaps as the interceptors escorted the bomber all the way until it landed at Yeşilköy Airfield.

With Turkey declaring war on the Axis Powers on Feb. 23, 1945, the Air Force deployed its aircraft close to its borders as a precautionary measure. Among these was a squadron of FW-190s based at Sarıgazi to defend the airspace around Istanbul. There was a fuel shortage at Sarıgazi and no production of aviation fuel in Turkey at the time.

Before the war, a contract has been signed for a fuel supply. An agreement was made with Standard Oil to supply fuel before the war, and Shell had also covered a portion of Turkey's aviation fuel needs. However, the majority of Turkey's oil needs were met by the Romanian Oil Company; it later became impossible for Romania to supply Turkey during the war after it was occupied by Germany.

To summarize, plans to turn the premises of the 2nd Air Supply & Maintenance Center Command in Kayseri, formerly known as the TOMTAŞ and Kayseri Tayyare Fabrikası (KTF), into a people's garden will become a reality in 2019.

The buried aircraft in Kayseri need to be recovered by a qualified team, restored and housed in a properly built aviation museum which befits Kayseri's important standing in Turkish aviation history. Funds to finance such a major endeavor are available in both Europe and the United States, and it all needs to be done at international standards.

I call on the Kayseri Municipality to take note of this situation and to take action to recover and restore these aircraft to their former glory so that the entire world may enjoy them once again.

* Op-ed contributor based in Istanbul, the author of "A Chronicle of Turkish Aviation"