© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2025

One of the first scholars who comes to mind in the field of the history of Islamic Science is Fuat Sezgin, who passed away at the age of 94 in Istanbul on Saturday morning. Having a worldwide reputation, Sezgin produced numerous masterpieces, developed new ideas, mentored many students and briefly devoted his whole life to find the undiscovered in the history of science. However, what makes Sezgin a world-renowned academic is his insistence on seeking the truth in the Eurocentric history of science that ignored the contribution and sometimes even presence of Muslim scholars in science. He also left behind a tangible life lesson for those who want to raise their voices against discrimination in the history of science and contribute to the common improvement of humanity. Today, I'm humbly penning this article to memorialize him by briefly talking about his marvelous and inspirational life, I believe Sezgin's life story has changed and will continue changing people's way of life into a better, more hardworking and idealistic style.

Born in Bitlis in southeastern Turkey in 1924 – one year after the foundation of the Republic in the country – Sezgin studied at the Faculty of Letters in the Oriental Institute of Istanbul University with the German orientalist and historian Hellmut Ritter (1892-1971). Ritter, who was a prominent academic in the field of Islamic Science and Orientalism, deeply affected his "hardworking student" Sezgin's future. Sezgin describes those days as follows:

"My teacher [Ritter] asked me one day how many hours I work a day. I said, I work 13-14 hours a day; then he said I cannot be a scientist with these work hours; if I want to be a real scientist, I should work more than 17 hours. After that, I continued working approximately 17 hours a day until the age of 70. After 70, I had to work less, which is 13-14 hours a day."

As all of us today complain about being busy with many significant issues in our daily lives, not sparing time to read, study or write, I think the above short memory of Sezgin is enough for us to accept the fact that we only generate excuses but nothing more or less.

Sezgin graduated from the Faculty of Letters in 1951 and then completed his Ph.D. thesis, "Sources of Bukhari" [a prominent Islamic scholar that worked on the hadiths], in the Department of Arabic Language and Literature in 1954. In his early days as an academic, Sezgin realized that there was something missing in the Eurocentric history of science. As he increased his work in this field, Sezgin realized that Islamic scientists and scholars weren't included in the modern history of science, but he was sure that this was a total "factual mistake." Having read German scientist Carl Brockelmann's (1868-1956) "History of the Islamic People" and "History of Arabic Literature," Sezgin again noticed many "factual and deliberate mistakes" in the books, and it was the inspiration for him to start dealing with the history of Islamic Science to seek and voice truth about the history of science.

It was not that easy to do because Turkey was experiencing political turbulence in those days in the late 1950s. A military coup was staged in 1960, and the government under the leadership of Democrat Party leader Adnan Menderes was overthrown. The effects of the military coup were felt in every corner of the country, including academia. A list of harmful professors was released by the junta government, including 36-year-old associate professor Sezgin. Sezgin describes his feelings about that:

"In 1960, there was a coup, the soldiers took over the administration of the state, established a committee called the National Education Committee, and one day they released a list concerning "which professors are harmful." Their lists were like law. Newspapers say that 147 professors were kicked out. I was one of them. … I took one of the newspapers and put it in my bag, went to the Süleymaniye Library, and immediately sent letters to three friends of mine, saying, "Find me a place, I will come." Two of them were from the U.S., and the other one was the former chancellor of Frankfurt University. All three promptly replied that they would be more than happy to see me in their academic world, but I preferred Frankfurt."

Following the coup, Sezgin went to Germany and started lecturing as a guest senior associate professor in Frankfurt University. Sezgin was determined to write a masterpiece about Islamic and Muslim scholars' contribution to the history of science. Intensifying his research in the university, he became a professor in 1966 and started publishing his work, while spending a lot of his time in Germany's and other countries' archives and libraries. He learned to speak 27 languages, including Hebrew, Latin, Arabic and German and examined almost 400,000 pieces in those libraries in over 60 countries. He played a great role in finding many undiscovered books and articles on the history of science and Muslims' contributions.

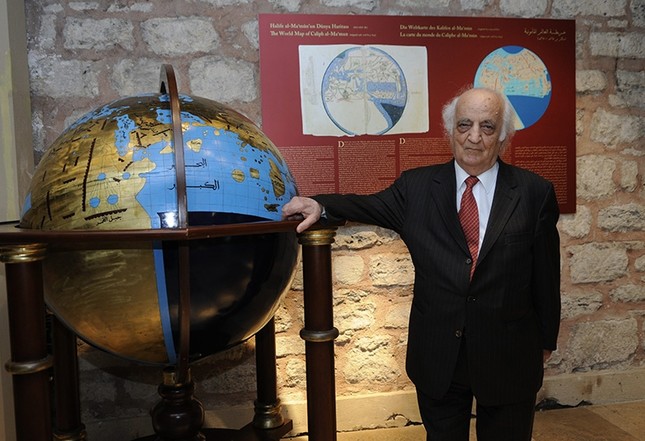

In 1978, he won the King Faisal prize for his works, thus found an opportunity to meet scholars and statesman of the Arab world and shared with them his ideas and project to establish a museum on Islamic Science. Finally, he managed to found the Museum of the History of Arab-Islamic Sciences under the J. W. Goethe University and worked as its director until May 2017. As designed by Sezgin, the museum exhibited samples of scientific inventions by Muslim scholars based on written sources. Later, with the support of then Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Sezgin founded the Museum of Islamic Science and Technology History in Gülhane, Sultanahmet, Istanbul.

The Museum of Islamic Science and Technology History in Gülhane, Istanbul.

Germany's unfortunate investigation

A few years later, Sezgin wanted to bring his own personal library in Frankfurt to his homeland to enable researchers in Istanbul to benefit. However, he faced an unfortunate and still ongoing investigation by the German authorities while trying to bring his books to Istanbul. German police prevented two-thirds of his books being brought to Turkey. The investigation, which obviously started due to political tensions between Ankara and Berlin, is still ongoing. German authorities' illegal behavior is very disrespectful to a scientist who spent almost his whole life in their country and contributed to their academic improvement. There are more details to be mentioned about it, but today, I'm feeling deep sorrow and do not want to talk about Berlin's political moves and will leave that subject to my next article.

In short, the world today lost a significant academic, Sezgin, who inspired millions of academics, and taught us the significance of seeking truth and finding the undiscovered in the world even when facing discrimination, prohibition and biased approaches.

* Ph.D. student in Constitutional Law at Istanbul Şehir University