A Swedish laboratory at Stockholm University has developed a toxic plant-based solution on which mosquitoes feed and die as part of a grand plan to fight diseases like malaria or dengue fever by specifically targeting the blood-sucking insects.

As field trials have been delayed repeatedly due to the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers in Sweden still believe they have found the secret to a new environmentally friendly way of eradicating the Anopheles species of mosquitoes that transmit malaria.

They are quite hopeful and have founded a company to turn their discovery into a commercially viable alternative to the pesticides currently used to kill mosquitoes and harm humans and the environment.

Researcher Noushin Emami, 44, jokes that it's like having a pet, but unlike a pet, these mosquitoes are tricked into drinking a poisoned chalice.

They are tricked because the liquid is spiked with the very molecule that makes humans infected with malaria so appetizing to them.

"If we add this molecule to any other solution, we make that solution very tasty for mosquitoes," said Emami, a molecular infection biologist at Stockholm University.

"Like the taste of a fresh baguette or a pizza for a hungry creature ... just out of the oven," she told Agence France-Presse (AFP).

In December, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported 241 million cases of malaria in 2020, up from 219 million in 2019, with an estimated 627,000 deaths – 96% of which were in Africa. Children under five accounted for about 80% of those deaths.

Malaria not only sickens people but those infected attract more mosquitoes and eventually more people are infected as the mosquitoes transmit the parasite.

In 2017, Emami and her fellow researchers discovered this was due to a specific molecule, dubbed HMBPP, released as the parasite that causes malaria, attacks the body's red blood cells.

'Eat it and die'

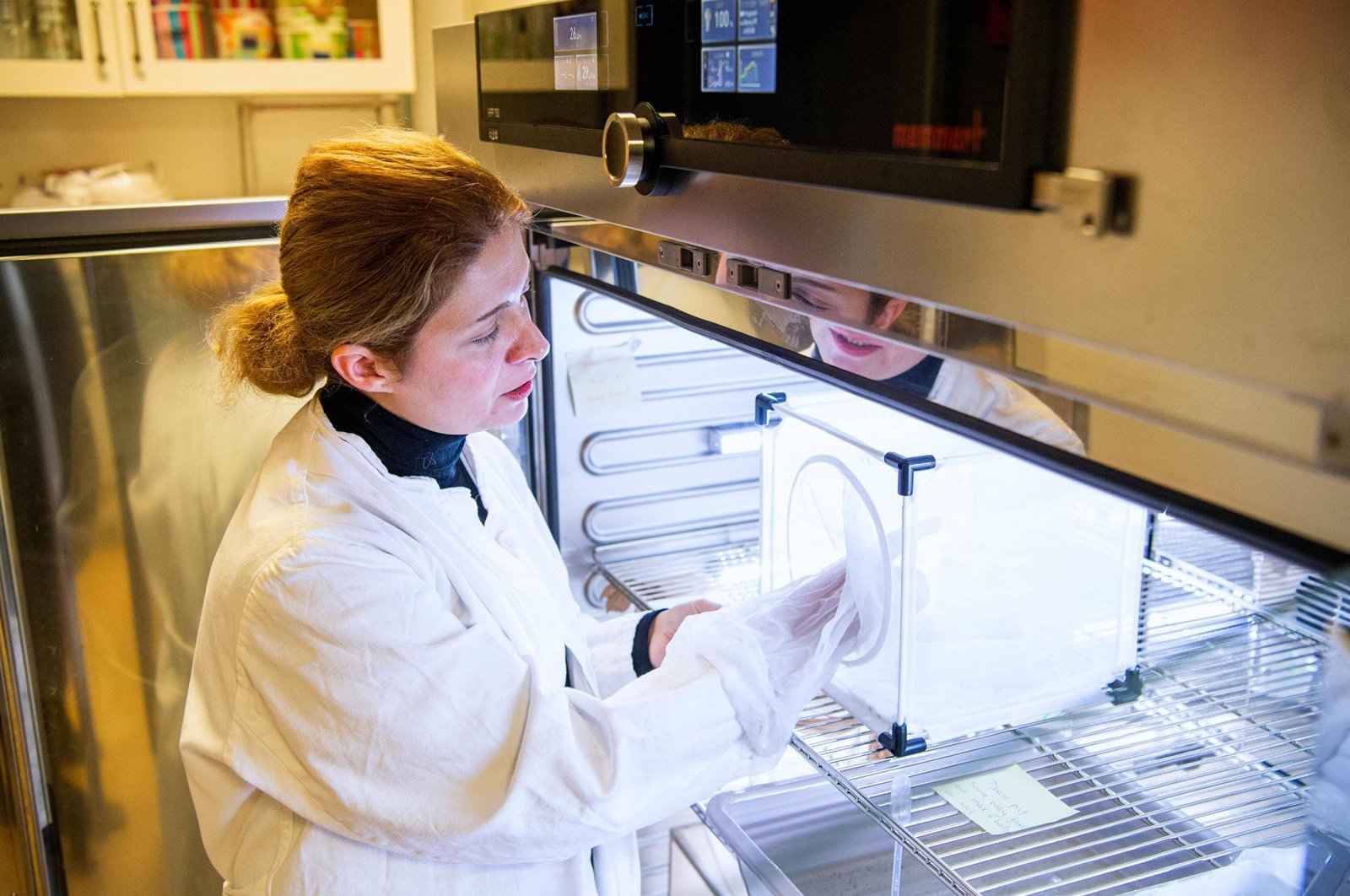

Opening what looks like a giant refrigerator kept to a temperature of 27 degrees Celsius (80 degrees Fahrenheit), Emami shows off shelves of water-filled containers full of wriggling larvae and the improvised mosquito cages, which she and her team feed daily.

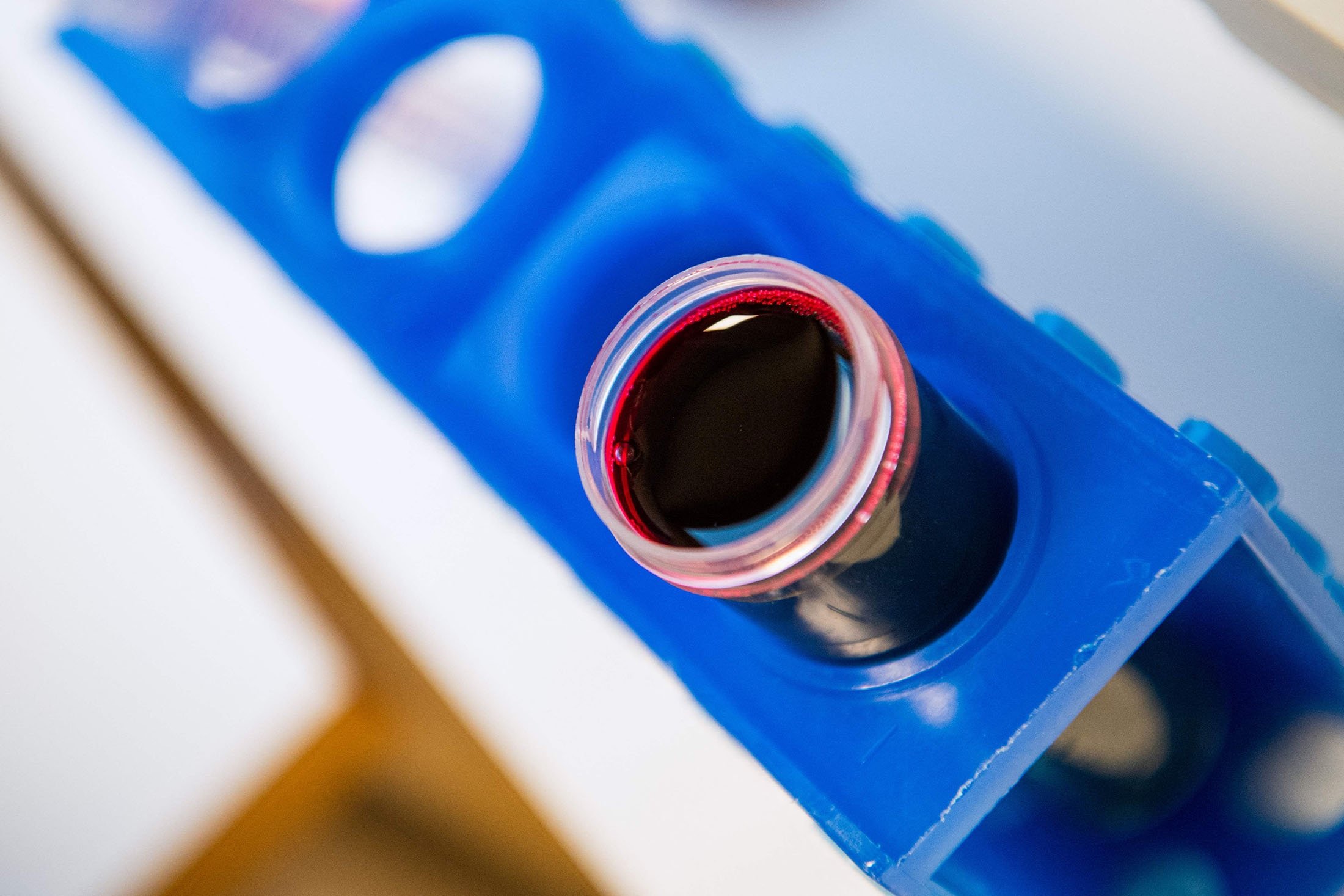

Adding to the beetroot juice – in place of human blood – "a trace amount of toxins combined with the molecule, mosquitoes eat it and die," explained Emami, an associate professor at the University of Greenwich in London.

The goal is also to use "harmless, environmentally friendly and easy to get killing-compounds."

Lech Ignatowicz, who together with Emami co-founded the company Molecular Attraction to commercialize the discovery, said the new method has the potential to drastically change the fight against mosquitoes spreading diseases.

"The most effective way of killing mosquitoes is still using pesticides, but we know that pesticides are not only killing mosquitoes, but also other insects and other forms of life," Ignatowicz told Agence France-Presse (AFP).

There is also evidence that pesticides are becoming less effective. Nearly 80 countries reported to the World Health Organization that mosquitos exhibited resistance to at least one of the four commonly used insecticides between 2010 and 2019.

'Problem scaling up'

Not only is the molecule relatively cheap, Ignatowicz said another benefit is how precisely it can target mosquitoes.

"Even in very dense environments, the jungle or tropical environments with a lot of insects, we can pick the ones we want to get rid of ... and leave the rest of the ecosystem alone," Ignatowicz said.

While the team is focusing on malaria, the method has the potential to be adapted in the fight to curb the spread of other diseases transmitted by insects or even rodents.

The next step is to start testing the method in the field.

Anders Lindstrom, a mosquito researcher at Sweden's National Veterinary Institute who is not connected to the project, told AFP he was "cautiously optimistic" about the method, but said much work remains to be done.

"The problem is always scaling up. The areas that need to be covered with these types of traps to get an effect are huge," Lindstrom explained.

Any method also needs to be applied consistently over time, which can be difficult in poor or conflict-hit areas where malaria is common.

"You can have a rather fast effect in reducing populations, but the moment you stop, they come back," Lindstrom said.