© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

First, they said don’t touch anything. Then they said keep your distance. Now what, don’t breathe?

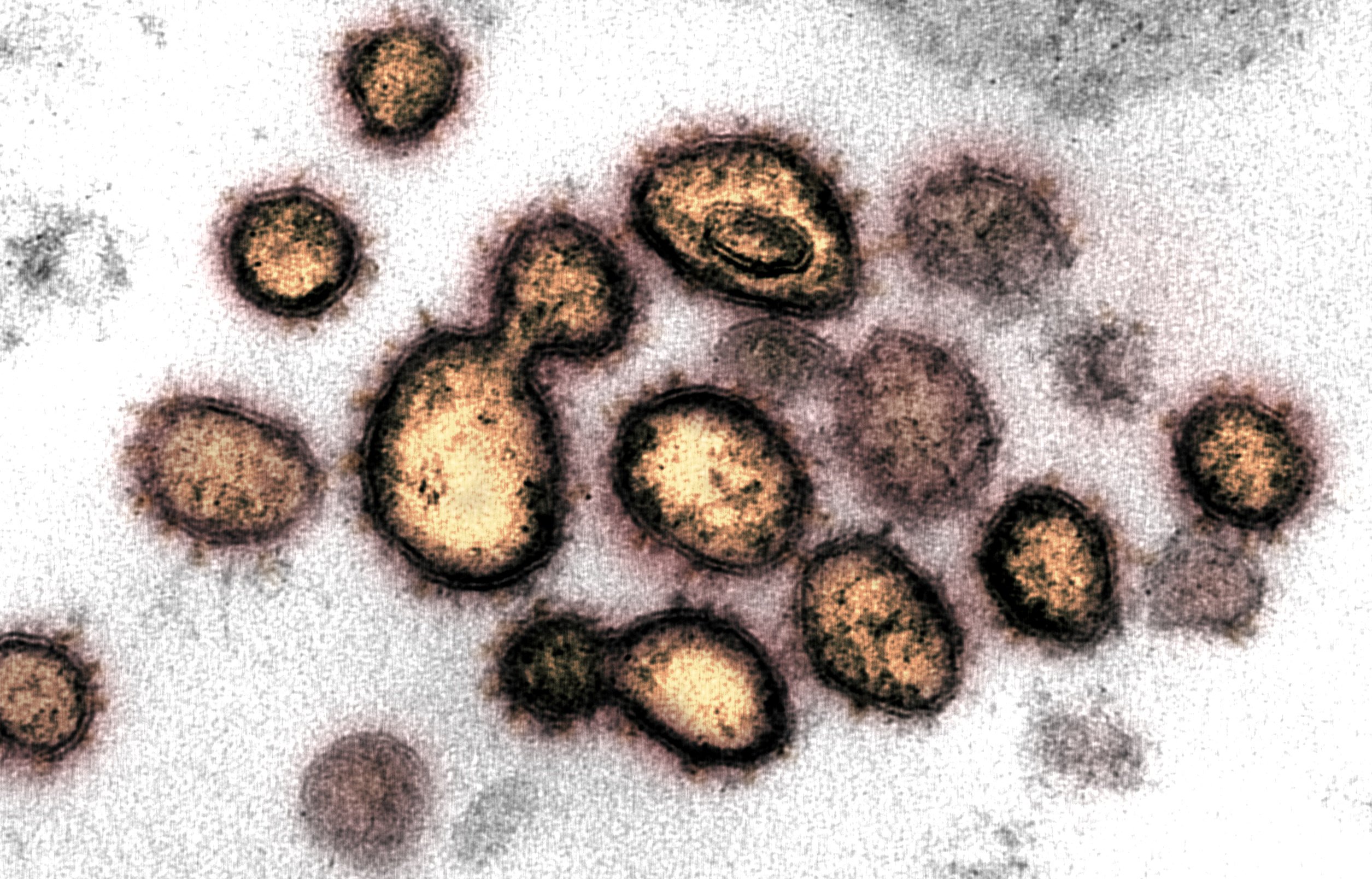

The coronavirus, which managed a firm grip on the world in a matter of months, seems to be more sinister than scientists initially thought.

With many countries still knee-deep in the first wave of the pandemic, as the U.S.' top infectious diseases expert Anthony Fauci said Monday, new evidence of the virus having a third pathway, namely aerosol transmission, has surfaced. A group of scientists have joined forces to campaign for greater recognition of this aerosol threat and are now pushing for change.

Here's what we knew up until now:

When a person infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, coughs, sneezes or just breathes, they expel droplets of various sizes.

Those larger than 5 to 10 micrometers, so less than the width of a typical strand of human hair, fall to the ground in mere seconds and within a meter or two of distance. This fact prompted health officials to issue warnings of social distancing and not touching surfaces, which we are all aware of.

However, it turns out that droplets under this size may not actually fall to the ground but remain aloft for several hours, traveling up to dozens of meters.

This revelation came to light only recently after more than 200 scientists in 32 countries penned a letter to the World Health Organization (WHO), urging the health agency to review and update its guidance on the coronavirus, complete with evidence that tiny airborne particles play a significant role in transmission. The general consensus so far had been that SARS-CoV-2 spreads primarily through droplets sprayed out from the nose and that these droplets quickly fell to the ground.

The open letter, published Monday in the Clinical Infectious Diseases journal, warns that they have found compelling evidence showing that floating virus particles can linger in the air as aerosol” and infect people who breathe them in. They have called on the WHO to take immediate action.

CASES FOR AND AGAINST

"There is significant potential for inhalation exposure to viruses in microscopic respiratory droplets (microdroplets) at short to medium distances (up to several meters, or room-scale)," wrote the authors, led by Lidia Morawska of the Queensland University of Technology.

"Handwashing and social distancing are appropriate, but in our view, insufficient to provide protection from virus-carrying respiratory microdroplets released into the air by infected people."

Cath Noakes, a professor of environmental engineering for buildings at the University of Leeds, who contributed to the paper, said COVID-19 doesn't spread in the air as easily as measles or tuberculosis but is a threat nonetheless.

"COVID-19 is more likely to be 'opportunistically' airborne and therefore poses a risk to people who are in the same room for long periods of time," she added.

However, not all experts are on the same page.

Dr. Benedetta Allegranzi, a top WHO expert on infection prevention and control, maintained that the aerosol theory was based on laboratory experiments rather than evidence from the field.

"We value and respect their opinions and contributions to this debate," Allegranzi wrote in an email. But in weekly teleconferences, a large majority of a group of more than 30 international experts advising the WHO has "not judged the existing evidence sufficiently convincing to consider airborne transmission as having an important role in COVID-19 spread."

She added that such transmission "would have resulted in many more cases and even more rapid spread of the virus."

The authors do recognize that the evidence for microdroplet transmission was "admittedly incomplete" but argued that the evidence for large droplets and surface transmission was also incomplete yet still formed the basis for health guidelines.

"The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence," said Julian Tang, an associate professor of respiratory sciences at the University of Leicester who contributed to the letter.

"The WHO says that there is insufficient evidence to prove aerosol/airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is happening. We are arguing that there is insufficient proof that aerosol/airborne transmission does not occur," he said.

Though initially quiet, the WHO has acknowledged that it was aware of the article, with spokesman Tarik Jasarevic saying they “are reviewing (the letter's) contents with our technical experts".

WHO officials have actually admitted that the virus can be transmitted through aerosols but have said it constitutes little risk as it occurs only during medical procedures such as intubation that can spew large quantities of the microscopic particles.

IN THE AIR FOR HOW LONG?

Several spreading incidents in the past have also forced scientists to reconsider airborne particles as a way of transmission.

The first case happened in January at a Chinese restaurant in Guangzhou where the airflow from an air conditioning unit appeared to waft the coronavirus to several tables, infecting several patrons.

Another study that appeared in a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicated that the virus was spread by microdroplets from people singing during a choir practice in Washington state in March. Fifty-three people fell ill at that event, and two died.

That is in addition to the fact that bars jam-packed with people have also emerged as hot spots for the contagion, with droplets of all sizes believed to contribute to the spread.

What this new way of transmission means for us can simply be put as: Poorly ventilated rooms, buses and other confined spaces are dangerous, even when we stay 6 feet, or 1.8 meters, apart from one another, we are still at risk of infection.

However, instead of getting caught up in a blind panic over the matter, the scientists that signed the letter argue that this evidence could be utilized in the fight against the virus.

Jose Jimenez, a University of Colorado chemist who signed the letter, said the idea of aerosol transmission should not frighten people. "It's not like the virus has changed," he said. "We think the virus has been transmitted this way all along and knowing about it helps protect us."

He and other scientists cited several studies supporting the idea that aerosol transmission is a serious threat.

One point that remains unclear about this new warning is how frequently this way of spreading can happen, especially when compared to larger droplets in coughs and sneezes. There has also been a debate in the scientific community about how infectious these microdroplets actually are.

Donald Milton, a University of Maryland environmental health professor and an expert on aerosols who co-wrote the letter, said the average person breathes 10,000 liters of air each day.

"You only need one infectious dose of the coronavirus in 10,000 liters, and it can be very hard to find it and prove that it's there, which is one of the problems we've had," he said.

WILL CHANGE COME SOON?

If the WHO does decide to change its guidance and update the virus’s risk of transmission, this may also force a lot of countries to overhaul their current public health measures to stifle the spread of the coronavirus.

Current WHO guidelines state that people should maintain a minimum distance of 1 meter (3.3 feet) and wear masks while out in public, preferably while also wearing eye protection.

Since the coronavirus was first detected in China in December, our understanding of how it spreads has evolved, resulting in shifting guidelines regarding the use of masks.

At first, masks were said to be overkill for ordinary people and should be conserved for health workers only. Later, experts recommended masks only for people exhibiting symptoms. A month later in April, it became clear that many cases of COVID-19 were asymptomatic, which contributed greatly to the rapid and quiet spread of the virus. Then some countries, including Turkey, mandated the use of masks, especially in crowded areas and when physical distancing was difficult. A practice the WHO was a bit late to adopt.

Experts reiterate that aerosol transmission appears to be the only way to explain these "super-spreading" events.

Proponents of aerosol transmission say wearing face masks correctly will help prevent the occurrence of exhaled aerosols as well as the inhalation of the microscopic particles. Improving ventilation and zapping indoor air with ultraviolet light from ceiling units could also help reduce its spread, they add.

The virus's body count continues to rise with each passing day. The latest statistics show that more than 537,000 people have lost their battle worldwide against COVID-19, while 11.6 million people have had unwelcome encounters with it.