© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

Scientists have discovered a new species of giant tortoise present on one of Ecuador's Galapagos Islands which was previously thought to be from another type after DNA testing found animals living on one island had not yet been recorded, Ecuador's environment ministry and Galapagos National Park said.

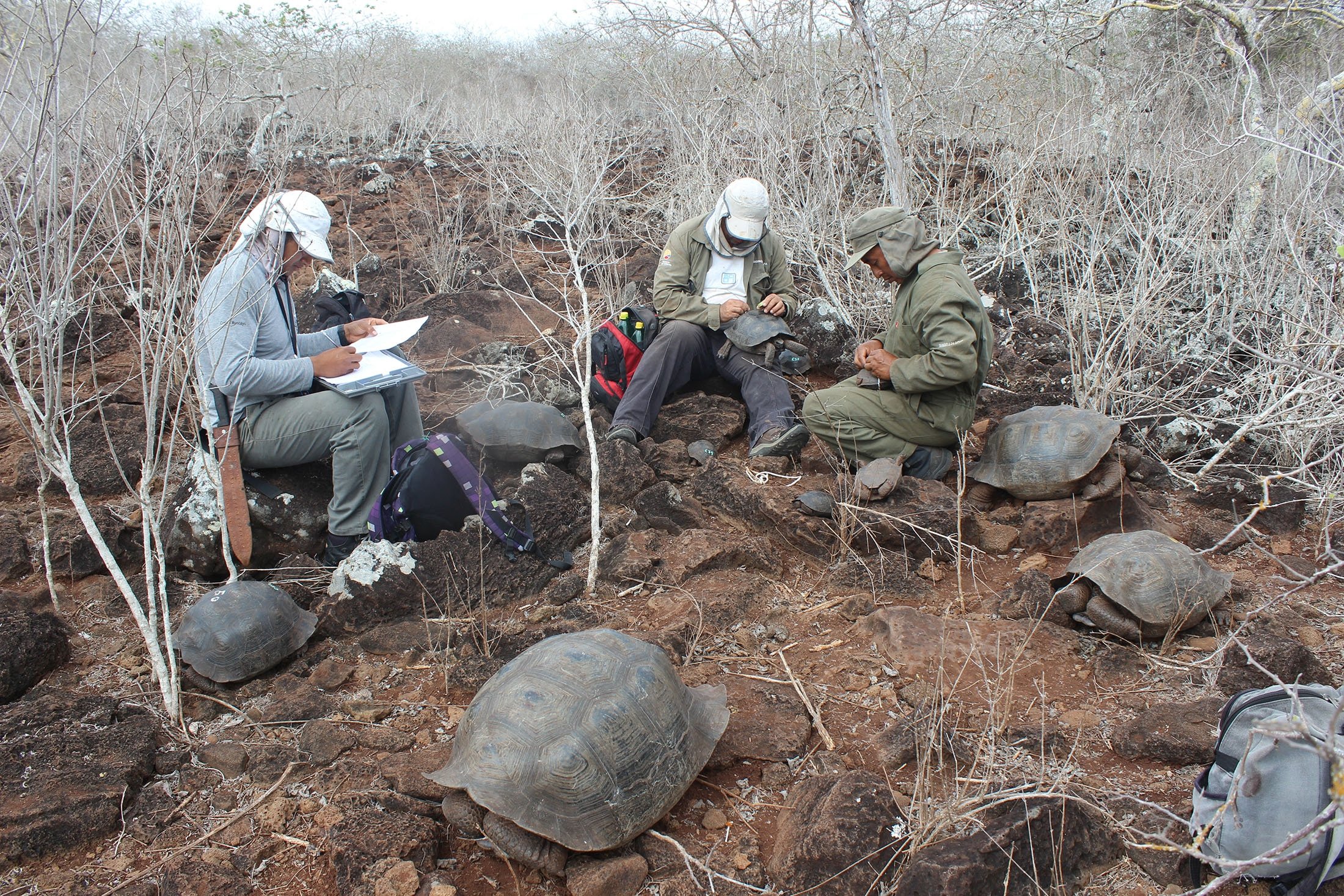

Researchers compared the genetic material of tortoises currently living on San Cristobal with bones and shells collected in 1906 from a cave in the island's highlands and found them to be different.

The 20th-century explorers never reached the lowlands northeast of the island, where the animals live today, and as a result, almost 8,000 tortoises correspond to a different lineage to what was previously thought.

"The species of giant tortoise that inhabits San Cristobal Island, until now known scientifically as Chelonoidis chathamensis, genetically matches a different species," the ministry said Thursday on Twitter.

Galapagos Conservancy said in a newsletter that the Chelonoidis chathamensis species is "almost certainly extinct" and that the island had in fact been home to two different varieties of tortoise, one living in the highlands and another in the lowlands.

Located in the Pacific about 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) off the coast of Ecuador, the Galapagos Islands are a protected wildlife area and home to unique species of flora and fauna.

The archipelago was made famous by British geologist and naturalist Charles Darwin's observations on evolution there.

There were originally 15 species of giant tortoise on the islands, three of which became extinct centuries ago, according to the Galapagos National Park.

In 2019, a specimen of Chelonoidis phantastica was found on Fernandina Island more than 100 years after the species was considered extinct.

The study by researchers from Newcastle University in Britain, Yale in the United States, the American nongovernmental organization (NGO) Galapagos Conservancy and other institutions was published in the scientific journal Heredity.

They will continue to recover more DNA from the bones and shells to determine whether the tortoises living on San Cristobal, which is 557 kilometers long, should be given a new name.