© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

The uncommon name, Zebercet, appears in the opening sentence of the novel, "Motherland Hotel" by Yusuf Atılgan, a writer who appears to have stamped the place of existentialism in postmodern Turkish literature with unparalleled verve. Zebercet is a hotel clerk and a mystifying one at that, ruled by his impulses. He is doggedly pursuant of a peculiarly mundane, however, unresolved, enigma, an empty room in his hotel.

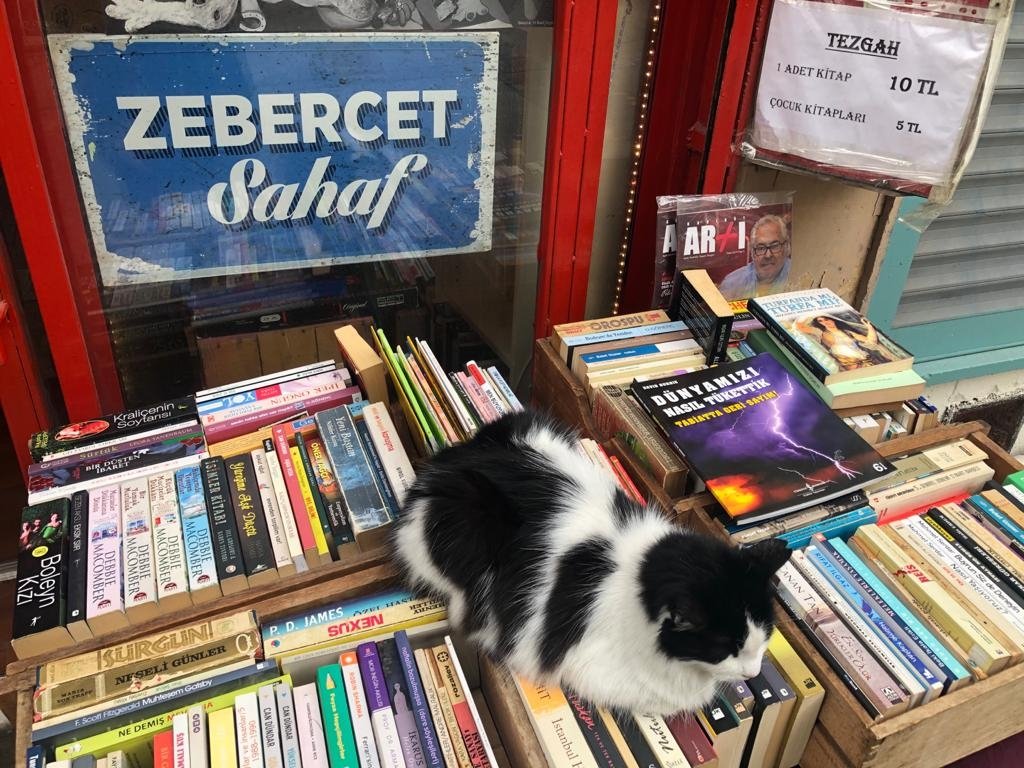

That same persistence, a psychological obsession perhaps, is at the heart of the will that drives the uniquely Turkish tradition of the sahaf, or used bookshop. In the face of temporal irrelevance and utter improbability, such storefronts as Zebercet in Kadıköy's Moda neighborhood in Istanbul remain open and, in fact, well-trammeled. On a perfectly normal Thursday afternoon, a group of youth sat around the friendly sahaf bookseller’s door and spoke of literature, life, their city and world.

On either side of the Zebercet sahaf, there are unlikely stores that speak of the neighborhood’s distinctive order of cultural sophistication. Moda Plak, meaning, Moda Vinyl, swings open, ready to entertain with its vintage sound systems, amplifiers. There is a soft lure to the record, its visceral resonance blending with urban physicality, especially complementing the sahaf beside it, wherein there are obscure Odeon presses of Russian classical music.

And on the other side of the irresistibly quaint crimson-painted storefront, there is a boutique clothier, offering its passersby a glimpse into opportune investments in new fashions of various fuzzy and frizzy varieties. Yet, on an uninspired humdrum weekday, under the light of a gleaming sun-drenched sky, as clouds pass intermittently, the sahaf confidently retains its poise in reference to a dustier plane of reality, where the past is held to the utmost esteem.

As with all others, the old friend of the sahaf is none other than the stray cat. They are like Sancho Panza to Don Quixote, the latter symbolic of the sahaf itself, going along on a rather eccentric adventure, self-revolving, anachronistic, yet, by the endearing nature of their waywardness, worth accompanying, if only for a fleeting stop in the midst of an afternoon walk. Atop books that Zebercet sells on its sidewalk, a black-and-white feline is often half-asleep.

Literary ancien regime

Outside the Zebercet sahaf, inside simple wooden boxes, are proud efforts in the struggle to accentuate Turkish literature’s broad taste for writers abroad: American, French, German and Russian. A slight push against the back leg of the stray cat, that while disturbed, refrains from swatting, is a 1971 translation of Henry Miller’s “Nexus,” a delicious mine of stylized 20th century prose at its finest.

More locally minded, such titles abound, as Buket Uzuner’s tale of Gallipoli, or a study of Turkish classics by Yahya Kemal. In the window, where a peruser might peer through into the overstocked interior, such covers as the child-friendly translation of a daily folktale compilation, or an outdated copy of a book on contemporary photography art stands ready for spirits of inquiry to fly, unencumbered by the worldly pressures of modernistic news-cycle adherence.

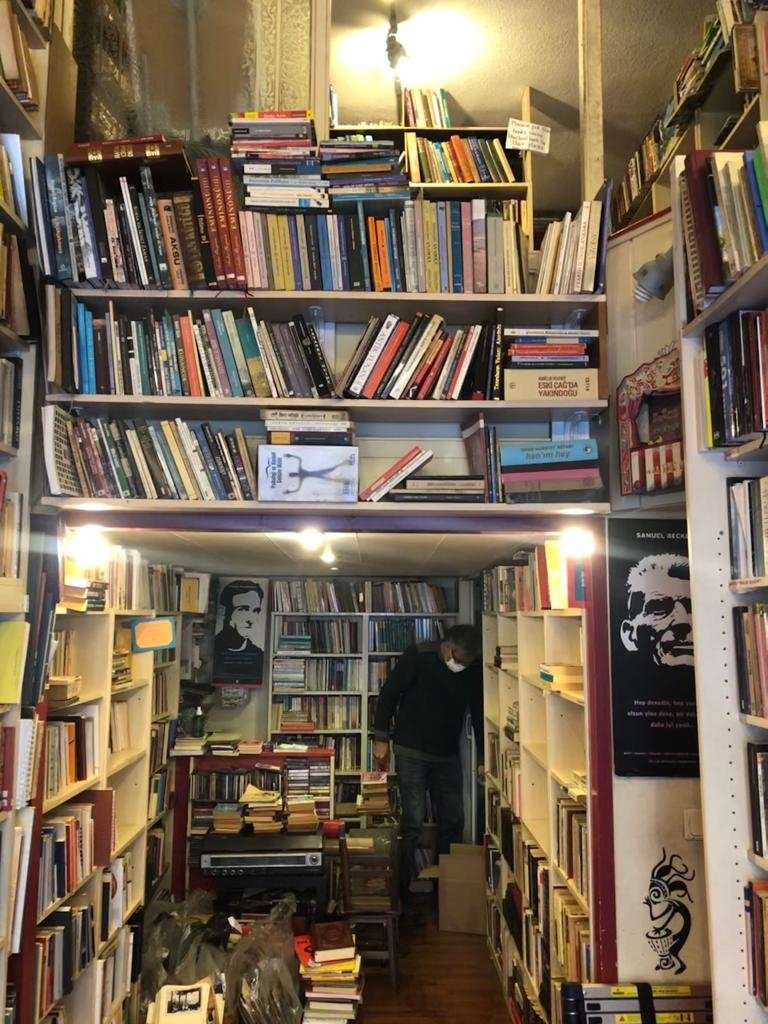

Inside, the faces of writers Chuck Palahniuk, a self-made yarn-spinner of legendary proportions among America’s history of popular letters, and Samuel Beckett, the indispensable dramatist of literary philosophy from the worldliness of Ireland’s stout linguistic talents. It is a split-level affair, with mostly Turkish material on the ground floor, and by way of a thin stairwell, a loft that leads to an assemblage of antique books from abroad that only a sahaf would carry.

The books of Zebercet sahaf are well-categorized, for all of its seeming haphazardness is merely a characteristic trait of the used bookstore, with some more disorderly than others. By virtue of its placement in the neighborhood, Zebercet, maintains a certain lucidity, so as to foreground what at times produces the rare surprise of a book that appears, as from nowhere, to speak directly to the collective subconscious of mutual intellectual interests shared by all.

An elderly woman on the other side of the world was remembering her days as a reader and through the fog of her fading eyesight, did not bemoan the loss but rejoiced in a life led with the joy of having read. One of her favorites, Taylor Caldwell, had written prolifically as a contemporary of Yusuf Atılgan. Her 12th novel, "Melissa," is a feminist portrait of a dissatisfied woman overwrought by choices in a world of men, a copy of which Zebercet acquired.

Toward the back

The bookseller of Zebercet sahaf is a kindly gentleman, whose tall height requires him to bend down slightly under the low ceiling, where, from his desk at the far opposite end against the entrance, he collects the change that issues from purchasers and answers the questions of students and literati who have come with interest or upon a fancy. He speaks English with an unselfconscious fluency and switches back to Turkish without skipping a beat.

The world of a sahaf is like a secret garden in which the act of smelling one flower opens the petals of another, which although different, makes for a harmonious bouquet of bookish discoveries. With enough erudition, seeing a collection of books, just the names, titles and covers, perhaps a quick skim of the opening pages, is like entering a cafe loud with the conversation of poets, philosophers and writers of the ages.

For example, the spine of a book by the Italian modernist, Italo Svevo, appears in Zebercet’s foreign fiction section, as translated into Turkish. His second book, the novel, Senilita, published in 1898, known in English as, "As a Man Grows Older," or "Emilio’s Carnival," had a direct influence on Turkish author Tezer Özlü, who, since her passing in 1986, returns to the bedsides and minds of her readers with a singular charm.

And as outside, so, within Zebercet, the Turkish literary culture of the 1970s is rife with intriguing intersections, particularly when it comes to the hard-knock prose of Brooklyn-born Parisian exile Henry Miller. The other volume of his diptych to Nexus, titled, “Plexus” is held within Zebercet’s welcoming shelves beside a slim, rare title of his, “The Smile at the Foot of the Ladder.” Translated into Turkish as early as 1967, it was Miller’s nonpareil Surrealist foray.

Looking back at the street, where varicolored protuberances protect pedestrians from the frequent passage of motor vehicles, from inside Zebercet sahaf, under its dim strings of light bulbs that reflect off the glossy, however, washed-out, posters celebrating long-outdated fame and fortune, the sahaf comes into its own as a space in which to gain not only knowledge but perspective, like reading its books, written decades ago, if not a century past.