© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

If Turkey’s beloved second-hand bookstores, known locally as sahaf, are where books go to pass away into oblivion, then there is one passage dedicated to their shops, in a kind of indoor mall by Galatasaray High School in Istanbul's Beyoğlu district. The passage might be seen as a stretch of bookish purgatory, a parallel universe for literati, bibliophiles, readers, bookworms, poets, scribes, writers and even the purely nostalgic, wayward, footsore urban wanderer to backtrack, one page at a time.

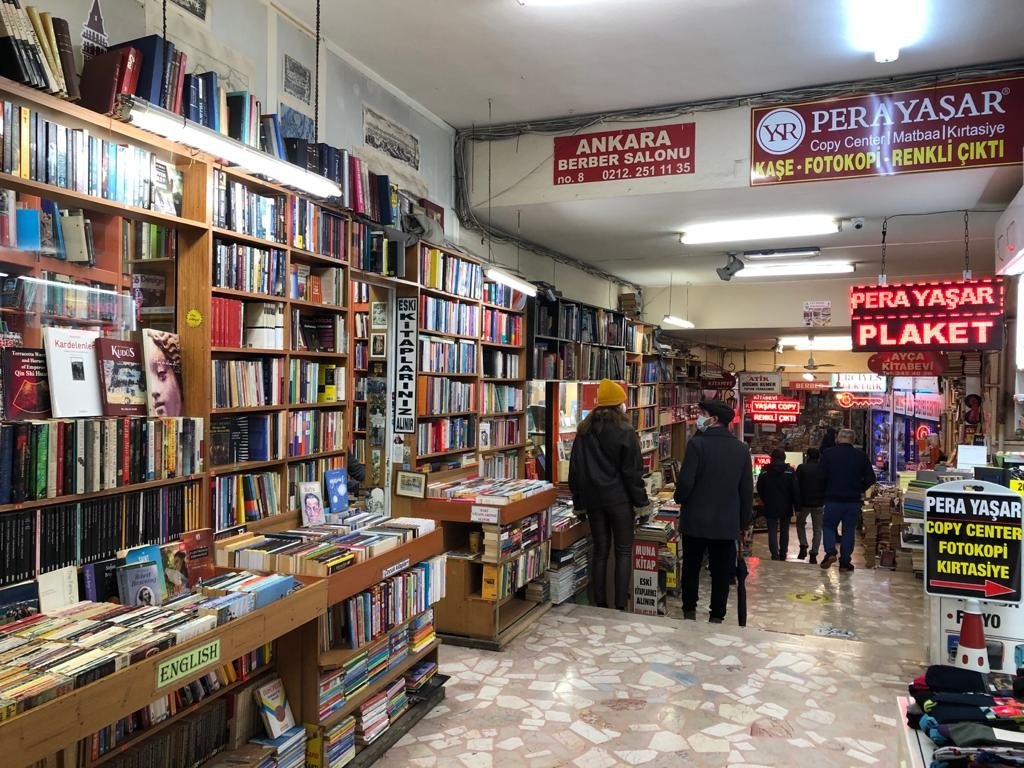

It is a world within worlds, like a book about books, ideal ground for anyone out for a figment of the past as its accumulation of dust piles high inside the course of hallways named, Aslıhan Pasajı, a market of sahaf bookstores that, like their books, are piled and stacked beside and on top of each other, to abandon, as overwhelmingly voluminous as the runaway thoughts of an overthinking neurotic on a particularly anxiety-ridden day.

The sahaf booksellers at Aslıhan Pasajı are about as diverse and eccentric as the books that they carry, however messily, in heaps that appear more like the waves of a stormy ocean than any intellectual organization of rectangular objects. And the shops themselves overlap, apparently sharing shelves at points, even the displays immediately outside of their closet-like storefronts end indistinguishably where the next slew of spines begins.

Yet, throughout its mass of tangled leaves, although often kindly delineated according to topic and language, there is not much for the contemporary English reader to find that might remain relevant to the cultural moment. That is, after all, not the point of such sahaf markets, offering, instead, occasional curiosities going back a century past, or entertaining, outlandish perusals across outmoded trends in popular, commercial publishing.

In a compartmentalized box, the unbearable titles of pharmacy paperbacks gleam with their rosy, kitsch coloration, glaring with fonts that convey wordplay titles and forgotten names attributed to efforts that emerged with a shelf life as trivial and cliche as the themes that their stories and characters rehashed. But within the bluntly abysmal, there are redeeming finds that would otherwise go unnoticed by the more erudite, uppish of browsers.

In between a lightly fictionalized travelogue and a generic autobiography is the posthumous 16th-century story collection of Marguerite, Queen of Navarre, known by its title, “Heptameron”, which, after the Greek, signifies the seven-day time span in which the 70 tales of the late Renaissance queen are grouped. Not far from the worn Penguin edition, and also in English, is a collection of poems by the famed Anglophone bard, Robert Browning.

For Turkish readers, the opening shops at Aslıhan Pasajı hold interesting examples of translation that span the breadth of 20th century writing from Turkey as it has conveyed itself to the world, and returned. The late author, Moris Farhi, originally from Ankara, spent his adult life after university in London, where he became a novelist who believed in Turkey’s modernism as an authentic source of universal humanism.

The penultimate novel by Farhi, titled, “A Designated Man”, appears with its cover presented boldly at the Aslıhan Pasajı sahaf market, in Turkish, as “Atanmış Erkek”. It is a bittersweet tale of Balkan rivalries, through the prism of gender equality. And the fact that Farhi, a Turkish writer, wrote novels solely in English, and that his books are sold in Turkey, in Turkish, speaks to the transcultural nature of literature as a relay race of shared histories in translation.

While perhaps not necessarily in relation to the titles themselves, the sahaf is a place where the work of independent publishers nestles deep into the nooks and niches of its obscure readerships, finding authentic appreciation for having been discovered at the end of a characterful venture. Such is the case with Sub Press, an underground imprint that deals in all things Beat, and counterculture.

One of the Sub Press publications, by American music writer Mark Opsasnick shows the rattled mien of Jim Morrison on the cover of “Coffee and Poetry”, in Turkish, a collection of writings on the lost history of late 20th-century coffeehouse culture. Its placement, near to a stack of magazines, “Hayat”, “Life”, in English, with the second, 1962 issue on top, demonstrates the distinctive contrasts of mainstream society during Morrisons’ early years.

It was said that Morrison himself read as diversely as the holdings of an Istanbul sahaf, from Plutarch to Arthur Rimbaud, Albert Camus to Jack Kerouac. In fact, at a particularly aesthetically-pleasing, vintage sahaf down the hall from the entrance at the Aslıhan Pasaj is Kozmos, in which the Turkish translations of Kerouac’s 1958 classic, Dharma Bums is sidelong under one of the best biographies on him, by his ex-girlfriend Joyce Johnson.

In the Istanbul sahaf, as they abound at the Aslıhan Pasajı, there are not only the histories of Turkish literature’s readers from the past hundred years or more, but of every culture that has ever come through the grand, historic multicultural, international crossroads of the Sublime Porte. It is no wonder, then, that American literary history is aired beside earlier English momentums of books, not merely as portals for the imagination, but as mementos.

At Kozmos, there is a well-kept bookcase, displayed at the entry, sandwiched among many others, of antique English, French and German books, many of which are translations from one of these languages into another. They are generally bound as illustrated hardcovers, as valuable as they are collectible, including works by Mikhail Lermontov, Stefan Zweig, and Mark Twain.

Among these dusty, worn volumes, one caught my eye, a collection of essays, literary and critical, by the English poet Matthew Arnold. The edition was a reprint, from 1911, and on the back of its cover, there was a charming note, in pen, by a loving daughter named Elizabeth, who in the winter of 1913, had gifted that book to her father for Christmas. It can only be surmised by some wild conjuration how it fell out of the family’s possession. Now, it is TL 50.

Unlike many of the other sahaf bookstores throughout Istanbul, which I have surveyed from Balat to Kadıköy, Beşiktaş to the Princes' Islands, Aslıhan Pasajı held a distinctive variety of books in rarer foreign languages than that mostly manufactured by Europe’s publishing market, such as a Dutch copy of the spectacular Sartre biography by the American art critic and writer Annie-Cohen Solal.

And venturing further, throughout both stories of adjacent, neighboring used bookstores of the sahaf kind at Aslıhan Pasajı, even in the cold, relatively airless confines of shops within shops housed within the indoor, whitely lit marketplace, many of the sahaf booksellers appear to inhabit ulterior dimensions of the human intellect. One eccentric sahaf bookseller therein can be found at his desk under a sign reading, Destine, humming to Latin grooves, surrounded by books that seemed to have teleported from other times, countries, imaginations.