© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

There is a secondhand bookseller across from the eastern entrance to Akmar Pasajı (the Akmar Passage), which might be understood, to an Anglophone, as a passage to an urban landscape that begins where Istanbul’s Anatolian neighborhoods stretch along the Sea of Marmara, welcoming travelers from the European side of the Bosporus with a bookish air. Its paginated redolence carries across the pedestrian mall to an older, bearded sort, who guards the closet-like space of the Müteferrika Sahaf with a hawkish eye.

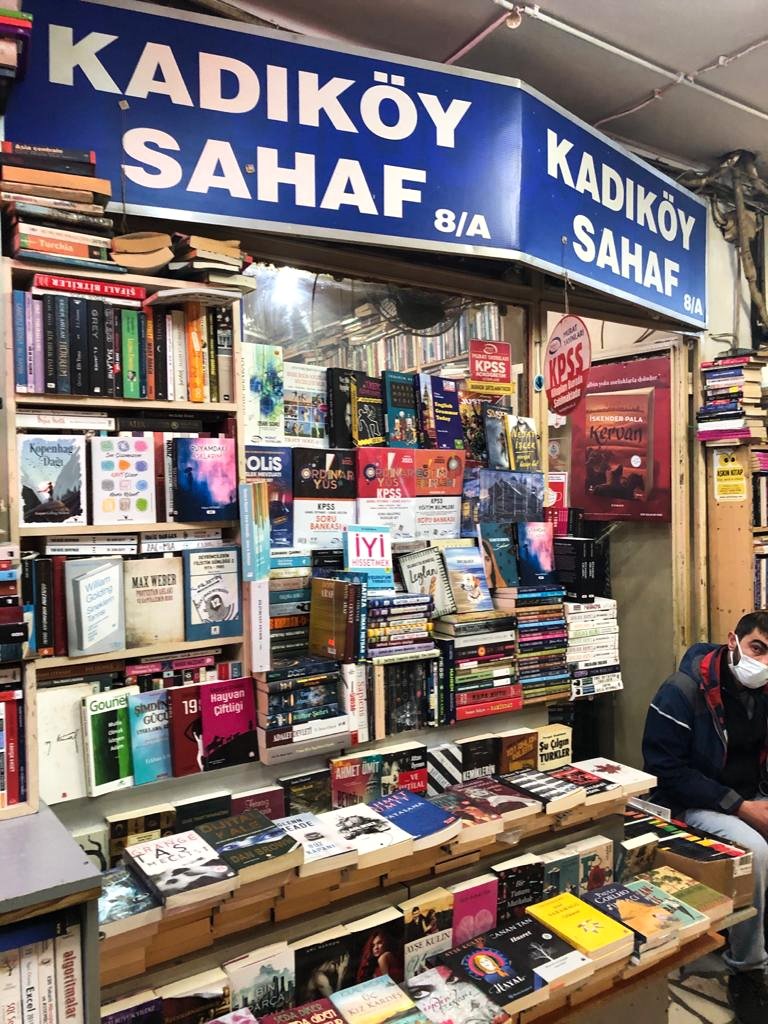

As is printed on his fading, crimson sign, his shop is typified as a sahaf, which might best translate into English as antiquarian, including mostly but not only vintage books. It is a store of obscure literary treasures that spills out into the carless street of walkers and sitters in Kadıköy district. Yet, there is an interior, however, difficult it might be to enter. It narrows to a point, like a thin, isosceles triangle. While it is certainly permissible to look at the books, and even write down their titles, photographing them is another story.

The erudite will know that Müteferrika refers to the first Ottoman printer, a convert to Islam from Hungary who came to be known as Ibrahim Müteferrika. In the 18th century, as a young Ottoman diplomat, he was a collector of books. When he began printing dictionaries, histories and scientific studies, he was ushering in a new chapter in the integration of modernism between the traditionally Muslim and Christian nations of Eurasia. The sahaf named after the pioneer printer also carries the eponymous, Müteferrika magazine on books.

On its outdoor display table, where a group of men congregates over tea and telephones, the Müteferrika Sahaf stacked a formidable collection of used books in English. One of them had an especially captivating title, "The Book as World" by Marilyn French, which could be regarded as a fresh way to appreciate literature, not as a practice in the acquisition and understanding of objects, or others, whether fictional, or representational, but as conceptual windows, or frames through which oneself appears, subject to creative thought.

And these are not simply variously sized rectangles fit with clear transparent glass, but form shapes previously unimagined, and are colored by filters that encompass the rainbow’s spectrum of refracted diversity. Some do follow a pattern and could be discerned as part of a tradition purposed to affect the reader so as to sympathize with the universal human condition through a specific lens of sociological or historical context. In Istanbul, it is natural to find such books as "Halide’s Gift" by Frances Kazan at Müteferrika Sahaf, since it reflects the locality.

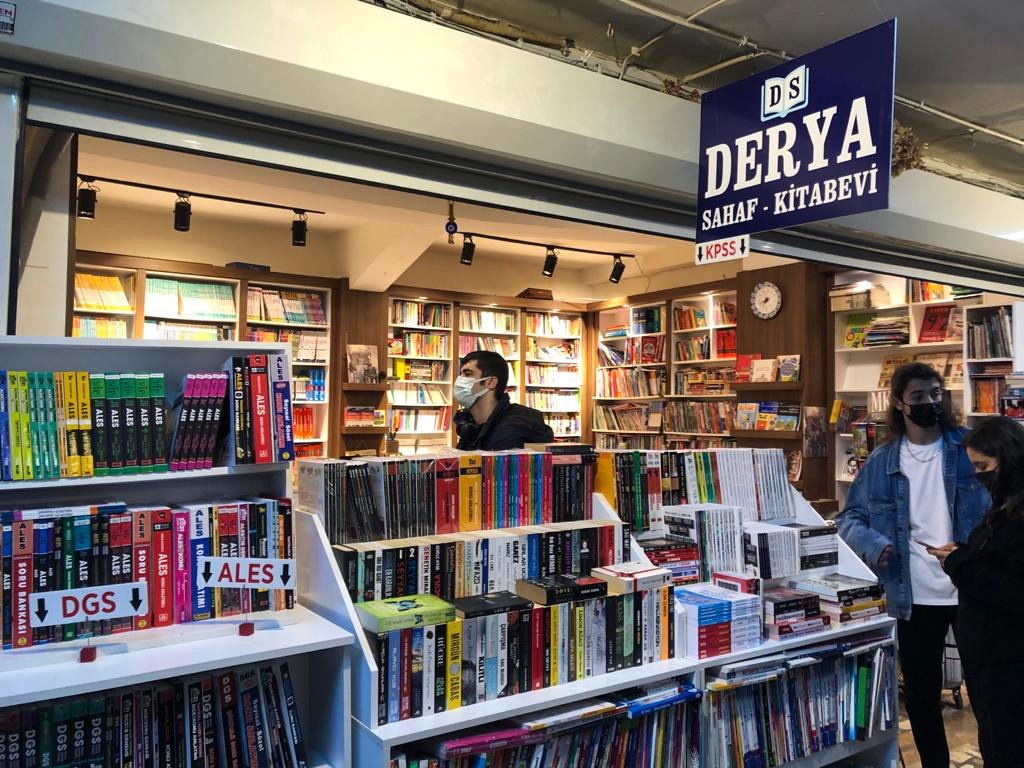

On either side of Akmar Pasajı, most researchers are students, as the book market purveys a hefty supply of textbooks, as a reliable source of material by which to embark on a self-education in the English language. Throughout its musty lengths, where booksellers greet with business cards and men in black leather jackets sip tea and listen to rock music, questions are often heard. A young woman asks persistently, “Do you have Ottoman poetry?” A group of backpack-suited teenagers ambles about in search of lost time.

Like a ride on the metro in Istanbul, the bookstores of the Akmar Pasajı are packed, side-by-side like sardines. If not a walk-in closet, their simple sales floors could be said to open like garages, yet often columned by walls lined with cracked spines. Its bookshops are generally a fusion of new and used, yet there are some that do specialize in secondhand. Among the few outlets with a strong sampling of perennial literature, of books by authors that remain canonical and urgent to the critical establishment, is a used bookshop called Sevgi.

Its compact space is all the more circumscribed by its stock, held within the furniture that ascends on a vertical plane like a range of steep mountains. Its tall bookshelves are stacked to the ceiling. There is a section where there are two hoards of English books facing each other. One is replete with commercial paperbacks long obsolescent beneath its capitalist overflow of rehashed plots and typecast characters. The other is a trove of breathtaking finds. It is not by coincidence that the literary masterworks are separated from pulp fiction.

Such sahaf bookshops as Sevgi at the Akmar Pasajı are testaments to the tenacity of craft literature despite the increasing virtualization of reading and the publication of new voices critically representative of largely unheard segments of global society. Nevertheless, within the deluge of contemporary cultural industries, the significance of past explorations of consciousness in writing not only holds water but assumes a distinctive, appreciable role as part of the ongoing conversation of intellectual history, like the staple genre of the classics.

The used bookshop, Sevgi, in that sense, is a free, public zone by which to realize the cusp where late modern thought crystallized into the postmodern. The moment, as it was analyzed and symbolized through different kinds of storytelling, discursive and metaphorical, could be said to have effected an attempt at psychological self-actualization on an international scale, toward a holistic embrace that includes all of collective memory. The idea of literature as a humanist project has ever been to portray and affirm absolute inclusivity.

By that single case of shelves in the Sevgi Sahaf, a person, even alone, and simply by the power inherent in literacy, might entertain the most enduring thoughts that have echoed across the grand valley of historic time. Among the impressive sweep of books, however, is one with a singular import for readers in Turkey aspiring to become bilingual. It is a novel by Kemal Demirel, entitled, "The People of Our Home," translated from the Turkish by Sylvia Meyer. The marvel of the publication is that it has printed the novel in both languages.

But in the stacks of Sevgi, there are studies and tracts, romances and adventures that would tingle the spine of anyone, from the university desk to the high plains. Thick chronicles like that of David Abulafia, whose book, "The Great Sea," is subtitled, "A Human History of the Mediterranean," stands ready for a buyer under comparably dense tracts exploring the literary, art, religious and political legacies of Western civilization. Its perennial authors, such as Marguerite Yourcenar demonstrated an eastward focus, as in her book, "Oriental Tales," at Sevgi.