© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

Pharmaceuticals and research labs across the world are racing to find vaccines and treatments for the new coronavirus, using a variety of different technologies. There are currently no proven treatments for the virus. Experts say it could take a year or more to have a vaccine ready. The hope is that strict quarantines around the globe will contain the spread long enough for scientists to develop tools to fight it.

Benjamin Neuman, a virologist at Texas A&M University-Texarkana, said immunizing against the pathogen is a long shot: There has never been a very successful human vaccine against any member of the coronavirus family.

"This is going to be a lot of trial, a lot of error, but we have a lot of options to try," Neuman said.

Treatment could come sooner. The decade-old antiviral remdesivir has shown early promise and has already been used on an ad hoc basis before regulatory approval. However, experts say a vaccine would require more time and research.

"A vaccine has to have a fundamental scientific basis. It has to be manufacturable. It has to be safe. This could take a year and a half – or much longer," wrote H. Holden Thorp, the editor-in-chief of the journal Science.

"Pharmaceutical executives have every incentive to get there quickly – they will be selling the vaccine after all – but thankfully, they also know that you can't break the laws of nature to get there."

The United States is funding several companies through the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and National Institutes of Health (NIH). The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), a global organization based in Oslo, is also helping to fund many companies, mostly smaller partners that would lack the capacity to scale-up mass production. It has so far provided about $24 million.

Firm: Gilead sciences

What it is: Treatment

When it might come: Later this year

Of all the drugs linked to the virus that causes COVID-19, Gilead's remdesivir could be the closest to market launch. It's actually not new per se but was developed to fight other viruses including Ebola, where it was shown to be ineffective, and it hasn't yet been approved for anything. Still, it has shown early promise in treating some coronavirus patients in China, according to doctors, and Gilead is moving ahead with final-stage clinical trials in Asia. It has also been used to treat at least one U.S. patient.

NIH's Anthony Fauci, a top government scientist overseeing the coronavirus response, has said it could be available in the next "several months."

"There's only one drug right now that we think may have real efficacy, and that's remdesivir," said Bruce Aylward, a World Health Organization official at a recent press conference in China.

Remdesivir gets modified inside the human body to become similar to one of the four building blocks of DNA, called nucleotides.

Neuman told Agence France-Presse (AFP) that when viruses copy themselves, they do it "quickly and a bit sloppily," meaning they might incorporate remdevisir into their structure – though human cells, which are more fastidious, won't make the same mistake. If the virus incorporates the remdesivir into itself, the drug adds unwanted mutations that can destroy the virus.

Firm: Moderna

What it is: Vaccine

When it might come: 12-18 months

Within weeks of Chinese researchers making the genome of the virus public, a team at the University of Texas at Austin was able to create a replica model of its spike protein, which attaches to and infects human cells, and an image it using a cryogenic (cooled) electron microscope. This replica is the basis for a vaccine candidate because it may provoke an immune response in the human body without causing harm – the classical method for developing vaccines based on principles dating back to the smallpox vaccine in 1796.

NIH is also working with Moderna, a relatively new firm founded in 2010, to make a vaccine using the protein's genetic information to grow it inside human muscle tissue, rather than having to inject it.

This information is stored in an intermediary transient substance called "messenger RNA" that carries genetic code from DNA to cells.

"The advantage is that it's really fast," said Jason McLellan, who led the UT Austin team, whereas the traditional approach of creating the protein outside is difficult to scale and takes a long time.

The vaccine began its first human trial on March 16 after being proven effective in mice. It could be available on the market in about a year and a half, ready in case the coronavirus outbreak continues until the next flu season, according to Fauci.

Firm: Regeneron

What it is: Treatment and vaccine

When it might come: No firm timeline

Regeneron last year developed an intravenous drug shown to significantly boost survival rates among Ebola patients using "monoclonal antibodies." To do this, they genetically modified mice to give them human-like immune systems. The mice are exposed to viruses, or weakened forms of them, in order to produce human antibodies, Christos Kyratsous, the company's vice president of research told AFP.

These antibodies are then isolated and screened to find the most potent ones, purified and given to humans intravenously.

"If everything goes well, we should know what our best antibodies are within the next few weeks," with human trials to begin by summer, said Kyratsous.

The drug could work as both a treatment and a vaccine by dosing up people before they are exposed, though these effects would be only temporary.

In the near term, they are also trying to repurpose another of their drugs devised using the same platform called Kevzara, which is approved to treat inflammation caused by arthritis.

This could help fight the lung inflammation seen in the severe forms of COVID-19 – in other words fighting a symptom as opposed to the virus itself.

Firm: Sanofi

What it is: Vaccine

When it might come: Not yet clear

The French drugmaker is partnering with the U.S. government to use a so-called "recombinant DNA platform" to produce a vaccine candidate. It takes the virus' DNA and combines it with DNA from a harmless virus, creating a chimera that can provoke an immune response. The antigens it produces can then be scaled up.

The technology is already the basis of Sanofi's influenza vaccine. The company believes it has a head start due to a SARS vaccine it developed that offered partial protection in animals.

David Loew, the company's head of vaccines, is reported to have said Sanofi expects to have a research candidate ready for lab testing within six months and for clinical study within a year and a half.

Firm: Inovio Pharmaceuticals

What it is: Vaccine

When it might come: Emergency supplies by year-end

Inovio, another U.S. biopharmaceutical, specializes in DNA vaccines – which work in a similar way to RNA vaccines explained above but work at an earlier link of the chain.

As an analogy, DNA can be thought of as a reference book in a library, while RNA is like a photocopy of a page from that book containing instructions to carry out a task.

"We plan to begin human clinical trials in the U.S. in April and soon thereafter in China and South Korea, where the outbreak is impacting the most people," said J. Joseph Kim, Inovio's president and CEO, in a statement.

"We plan on delivering 1 million doses by year-end with existing resources and capacity."

Efforts on the Turkish front

Firm: BionTech

What it is: Vaccine

When it might come: Not yet clear

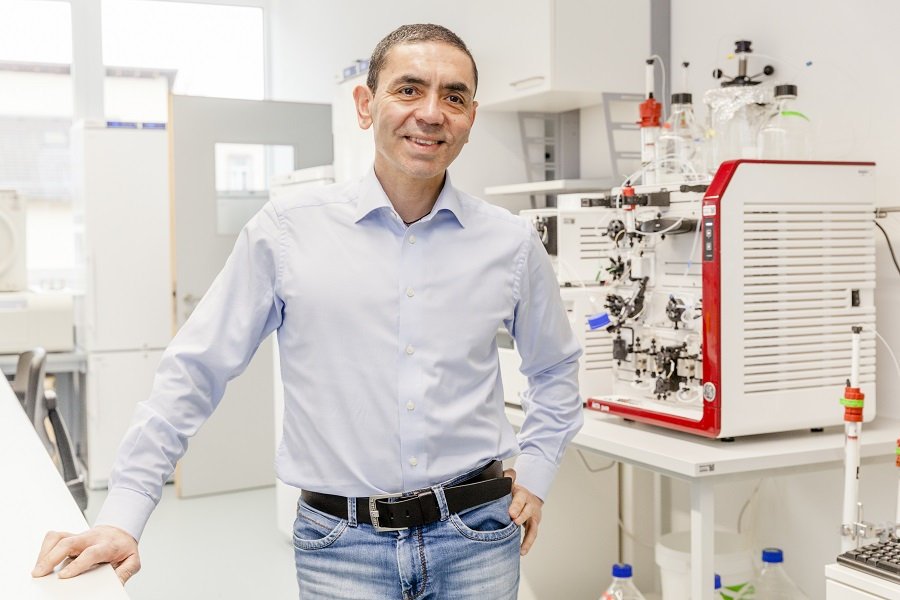

BioNTech, a Turkish-founded pharmaceutical company in Germany, also recently joined the race, signing contracts with Chinese Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceuticals and U.S.-based medical giant Pfizer to jointly develop its mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine.

The company, owned by Turkish scientist professor Uğur Şahin, said it will collaborate on developing its "BNT 162" shot, conducting clinical trials and the marketing of the finished product in China with Fosun, while it will own all rights for the vaccine in other international markets and work with Pfizer to co-develop and distribute it in zones, excluding China.

Clinical trials for the shot will begin by the end of April, the company said a statement March 17.

"In addition, we are working on a novel therapeutic approach for those patients who have already been infected – we plan to disclose more on that effort in the coming weeks,” said Şahin.

Test kits

Serhat Pala and his wife Zeynep Ilgaz Pala, a Turkish couple living in the U.S., announced that they can produce testing kits that can diagnose COVID-19 within three to 10 minutes.

As part of their work for their San Diego-based company "Confirm Biosciences," the couple said their test has already advanced to the production stage. Unlike its competitors, the test uses a blood sample, instead of taking swabs from the nose and mouth.

The test has been sent to China, Europe and other continents. The couple said their aim is to produce 500,000 tests per day so health institutions and hospitals can provide rapid diagnostic tests for the virus and offer medical treatment to a larger number of people in a shorter amount of time.

Other notable efforts

British drugmaker GlaxoSmithKline has teamed up with a Chinese biotech firm, providing adjuvant platform technology. An adjuvant is added to some vaccines to enhance the immune response, thereby creating a stronger and longer-lasting immunity against infections than the vaccine alone.

Like Moderna, CureVac is working with the University of Queensland on a messenger RNA vaccine. Its CEO Daniel Menichella met with the White House earlier this month and announced the company expects to have a candidate within a few months.

American pharmaceutical company Johnson & Johnson wants to repurpose some of its existing drugs to see how they might help treat the symptoms of patients already infected with the virus. It's also working on developing a vaccine involving a deactivated version of the pathogen.

California-based Vir biotechnology has isolated antibodies from SARS survivors and is looking to see if these can treat the new coronavirus. Its platform has previously developed treatments for Ebola and other diseases.

Even the likes of chloroquine – the synthetic form of quinine used to treat malaria – may have some properties that fight the virus, and scientists are calling for more work to investigate.