© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

If fashion is a medium that reflects your aura, the embodiment of your feelings for the day, or the transmitter of the signal you want to give to others, if it is the impression you leave on others before you even get the chance to express yourself verbally, it could be so much more.

Think about it. Fashion harnesses so much power — the power to change beliefs, visions, behavior, and you need only look at history for evidence of it.

It is a tool to reach the masses, no just through social media but also physically, from a remote village in India to suburban Paris and even the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean.

"How can I utilize this reach, this power, this tool to elicit widespread social change?" Öykü Özgencil asked herself.

And thus was born Incomplit.

"It was exciting to see this brand evolve into a tool that enabled people to say 'this is what I believe about social or societal issues,' to be able to come together with different communities and listen to their stories and dreams, and to create products, collectively, out of all these (valuable) dialogs," Özgencil tells me from across the screen. In a creamy white turtleneck, she leans against a backdrop in a shade of the most beautiful sea green I've ever laid eyes on, her long wavy hair reminding me of mermaids.

Incomplit wanted to dissipate this message to the masses via artistic outputs. The creative team would think on a problem affecting others, long and hard, but it would remain incomplete until it was assigned meaning with the stories of these communities and blended with their feelings.

"Is that where the name comes from? But why the misspelling (of the brand name)?" I ask.

To get others talking? Partly, yes, she says. And partly a reference to literature, of how the brand started with tales as old as time and partly a subconscious message to get people to light the fire inside them.

Communal belonging

After spending a year at Berkeley specializing in marketing, her dream was to create an environment free of judgment, one that encouraged dialogue and embraced differences. She wanted to bring together “disadvantaged” groups and listen firsthand to their problems before creating solutions.

"I don’t really like to say disadvantaged. I’d rather just say different. I wanted these people to openly share their issues, the things that made them feel not so good about themselves and help them gain their own perspectives."

She didn’t want to be imposing; being didactic was not her style, rather it was to encourage discussion, debate and creativity among these communities and draw from that experience to come up with a solution for their needs.

Then she wanted to incorporate art into it – to bring new perspectives into the mix about one’s own inner world and about the world outside

This journey of self-discovery would need funding, on a grand scale. That’s where the world of fashion and textiles swooped in like a savior.

"This sector has such a wide reach and is so easily accessible that I couldn’t think of a better way," she said. The fact that this industry is also one of the main consumers (in the world) gave her the incentive to right some wrongs.

All of this consumption comes attached with a hefty price tag – a burden on people and exploiting nature.

And that’s what got Öykü thinking about ways to lessen the harm caused by fashion to Earth, nature and people, and integrate it into this passion project.

What inspired her to create such a brand that relies so heavily on community spirit?

"I always dreamt of working for an NGO, but I faced disappointment time after time /through internships). ... Then I thought, why not create my own? But what really moved me to get working on this (brand) was a sense of belonging," she says.

To belong to a community is humankind's most basic need. There are also few bonds in life that are stronger than one established through sharing vulnerabilities – things that make you feel less than you are, those that drag you down or make you feel disadvantaged. These "weaknesses" can bring you closer faster than anything.

"Sharing similar stories with other people, no matter how different they may seem to you at first, it becomes really easy to empathize with someone who has lived through similar events as you. And that connection is so very strong," says Özgencil.

This kind of sharing also enables a collective interconnection, where people notice that they are tied to others with invisible strings despite coming from different socioeconomic backgrounds or cultures.

"That's what it is to be human. We can't get far in life without other humans. That's one thing the pandemic has shown us," she says.

Pandemic teachings

COVID-19 has heightened awareness about life, humans’ need for connection, the environment and fashion.

"We’ve seen a growing sociopolitical revolt in the past few years in the world of fashion, and I believe it can be used as a much bigger carrier of messages," says Özgencil.

Every season, fashion has this amazing power to convey messages to millions of people through fashion houses, independent designers and brands, she says. "Its area of impact is huge, especially when compared to a furniture brand, for example."

And that calls for sustainability.

Özgencil says there is both an ecological side and a social side to sustainability.

To be environmentally responsible in a world where fashion is the second biggest polluter, Özgencil said she wanted Incomplit to be transparent.

By using only locally produced materials and dyes, all within Turkish borders, she wanted to lower her carbon footprint. By choosing to produce only a select few items instead of dozens and using organic cotton, she would also lower the brand's water usage and prevent mountains of fabric waste collecting in ateliers.

From an upcycling perspective, she wanted to reuse materials deemed "unfit for sewing," as her master tailor Hamit jokingly yet annoyingly put it, and even managed to create bags out of coffee sacks.

"It was hard to convince our tailors to work with such hard materials. (Hamit) he would always show me all his beautiful but synthetic fabrics, asking me why we couldn't use them. Then I would explain to him what we were trying to do – to reintroduce a material that was written off as having served its purpose back into the loop. They learned about the circular economy and gained new skills out of this project," she said. A win-win for all.

And from a human-first aspect, she would ensure that no one involved was exploited, their voices were heard and they got their efforts' worth.

Keeping these steps succinct, sharing and championing collective benefit over individual gains laid the foundations for Incomplit's design and production principles.

Transcending boundaries

The ideation process of a product or collection for Incomplit isn't the same as a normal fashion brand.

"It's not that we sit there and think let's do a kaftan and then find a community whose backstory pairs well this item of clothing," says Özgencil, in fact, it's quite the contrary.

"After we contact a collective, a community or group of people, we sit down and talk about the hardships they face, and from there the creative process shapes the end product. After we've set the narrative, then we may think that the story evokes a kaftan, for example," she says.

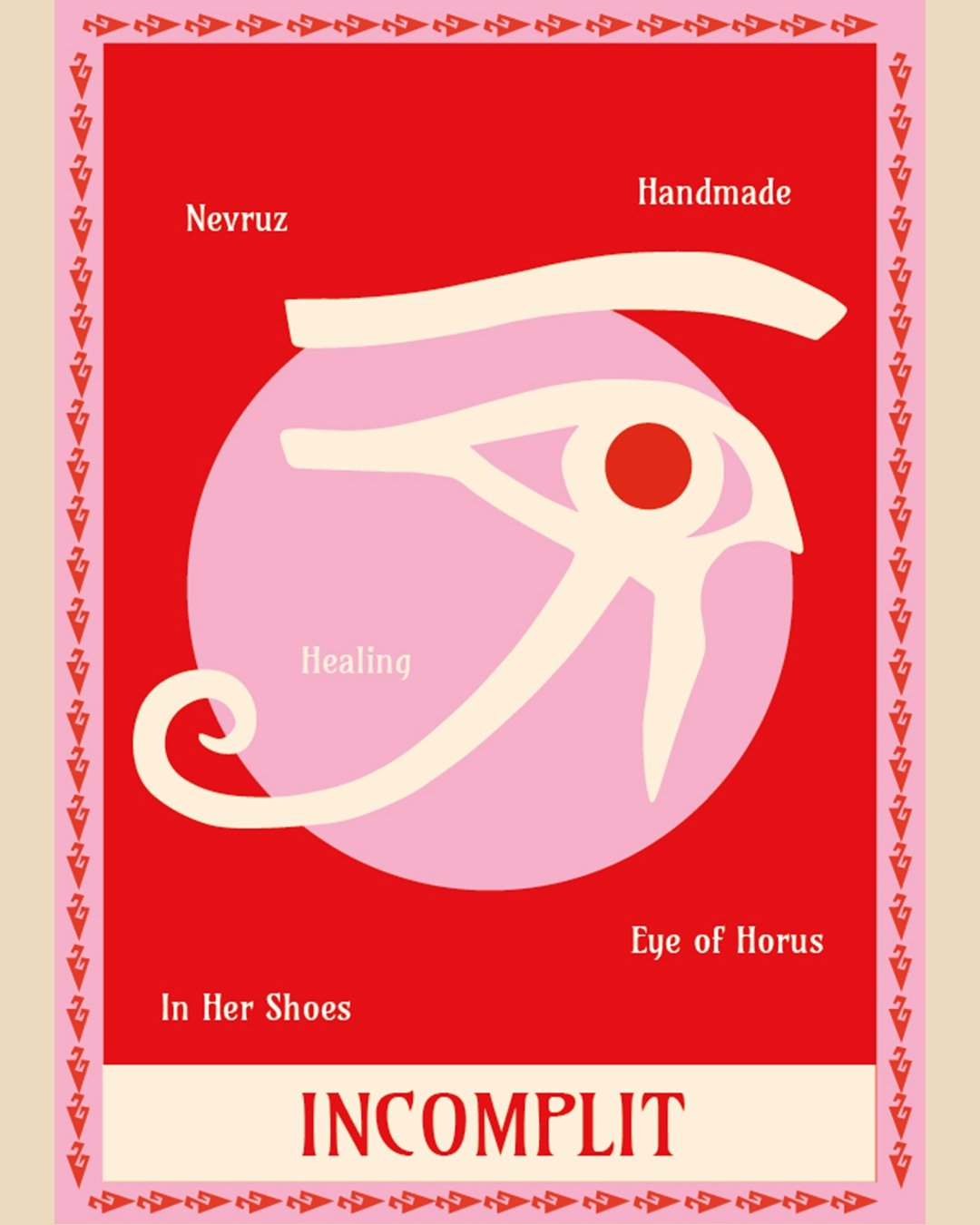

Among Incomplit's creations, installations and collections there are perhaps two that stand out the most: the kaftans and the patiks, or traditional Turkish knitted booties.

"We've also accepted as our mission to prevent cultural values from being lost or forgotten," explains Özgencil.

We like to tell stories through cuts, models and motifs we've seen throughout history, to bring to light those cultural roots, she says. There has also been a rise in interest in traditional Turkish motifs, handcrafts and artisanship in recent years.

That's why Incomplit gravitated toward patiks.

"They were also made from wool, which is a material you can carry with you anywhere. It’s something Turks have kept with them since they were a nomadic tribe as well. Nowadays, it’s not hard to get hold of and doesn’t cost much either," she says.

The booties were a part of the "In Her Shoes" project, which combines the stories and vision of two socioeconomically different groups of women. On one hand, there are the women who knit and sew at home to contribute to the budget of the household and on the other are some of the most important names leading the feminist art movement in Turkey.

Özgencil said they wanted to draw attention to how patriarchal society views women and the products they create by hand.

Handcrafts are increasingly being forgotten because the necessary value isn't attached to them and "homemade" products created by women are seen as unworthy, compared to, say, machine-made clothes, she explained.

"It was more of a participatory art project than a fashion collection," she added.

"We also operate more like a design studio rather than a fashion label," she says, which was one of the many reasons she showcases the collections, projects or installations in public spaces instead of high-class galleries, which made them more accessible for everyone. Without making people feel small or having to fork out money, Özgencil said this was key to carry the messaging in these stories to the masses, and thanks to fashion she is achieving that bit by bit.