© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

The sign on the wall reads in big, bold, red letters "14 days without accident."

You’d expect that this was a description of a scene from "The Simpsons," inside the animated series' infamous disaster-stricken nuclear plant.

However, Ezgi Utan was at an electronic goods company in Shanghai when she saw those very words on the wall. The year was 2012 and it was a factory of a renowned, quality producer of home goods and appliances.

Your, and her, immediate instinct is perhaps to think how bizarre it is to see a real-life example of an old custom/cartoon prop. These thoughts, though, quickly change direction, sending your mind buzzing with disaster scenarios after focusing on that small, two-digit number: 14. What happened that reset that figure back to zero? Was a worker hurt or worse, killed?

Considering the sharp parts and heavy equipment and that the smallest of cuts is considered an accident, perhaps it's not that shocking. But then one remembers the garment factory collapse at Rana Plaza that killed over 1,100 workers in Bangladesh in 2013, and instantly, you can see how this could have been a sign hung up on a textile factory producing for fast fashion chains.

Textile workers may not always be dealing with heavy machinery, but they are subject to over 8,000 toxic chemicals every day at several different stages, from dying fabrics to coating finished pieces, and often without the necessary safety protections. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), one worker dies every 30 seconds from being exposed to toxic chemicals in the fashion and textiles industry. Toxicity is a word that shouldn't carelessly be thrown around, after all the dose makes the poison and even too much water can kill you, but formaldehyde, perfluorocarbons (PFCs) and many other chemicals, which these workers come into direct contact with every day, have been linked to rashes, respiratory problems and even cancer.

"There is something wrong, a malfunctioning in the system if you make a conscious choice to buy a product but it gives cancer to a farmer in another corner of the world, if it forces producers to work under unfair conditions that go against human rights, if it leads to chemical contamination in our water resources and food chain," she said. That's the awareness and knowledge that led Utan to create Lando Studio.

When Ezgi Utan decided to found her brand Lando Studio, she wasn't aware of how dirty fashion was.

"I was oblivious to the fact that fashion and textiles were the second biggest polluter in the world, only after oil," she said. More than a fifth of industrial pollution worldwide also comes from the textile manufacturing process which pushed Utan to seek cleaner, safer ways to produce clothing.

She started by eliminating pesticides and harmful chemicals from her production line and went with organic cotton over conventional, using 60% less water.

She ensured that each item was made from organic, recycled and ecological fabrics, according to the Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) – the current most reliable certification, the Global Recycle Standard (GRS) and the LENZING certification for eco-responsible viscose fibers derived from certified sustainable wood and pulp.

Then it came to the human aspect.

"Unfortunately, the textile industry forces farmers and producers to work under very unfair conditions. Due to the inequality in income distribution, farmers and producers are always on the side that is oppressed and forced to back down, unable to resist injustice," Utan explained. Even in the pandemic when supply chains were disrupted, textile workers were the first in line to receive pay cuts or to be let go. Despite Oxfam revealing that billionaires' wealth increased by $3.9 trillion between March and December last year and workers losing $3.7 trillion during the same period, the working class always gets the bad end of the bargain.

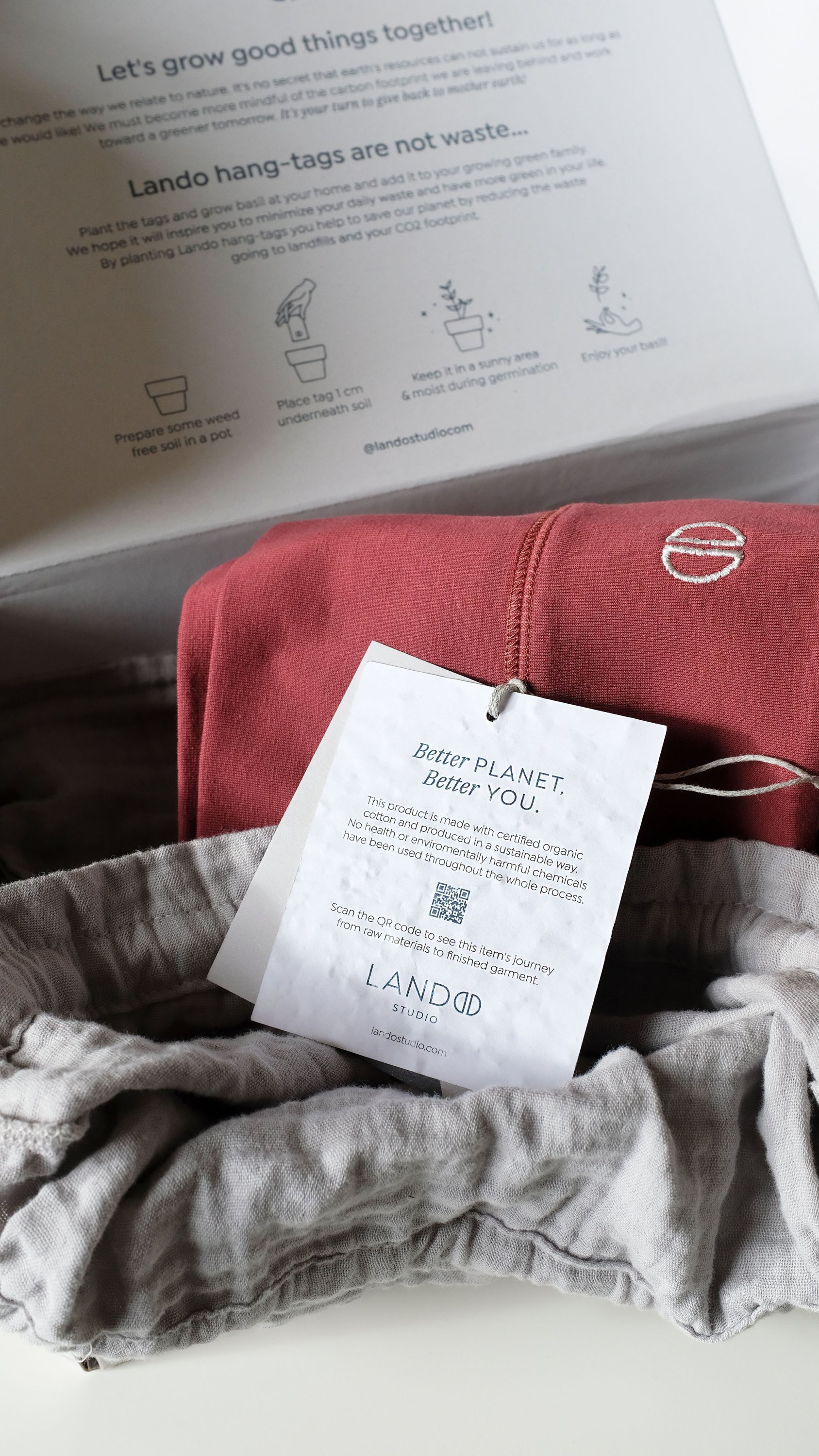

Hence, transparency has been of utmost importance for Utan, which spurred her to create QR codes on each item of clothing she created, detailing its journey from its cultivation in cotton fields to the hands that sewed its final seams. Of creative mind and perfectionist nature, Utan also paid attention to her branding, down to the labeling.

She asked: If you had collected every single label you've ever ripped off a piece of clothing and thrown directly into the bin, how much waste would you have accumulated? This seemed a good point to start change, and hence Lando Studio went with biodegradable labels with an eco-friendly surprise inside. Filled with basil seeds, Utan encourages its customers to make their own kitchen garden, which they can eat and grow as they please, while helping reduce their carbon footprint.

Yoga has always been a part of Utan's life. From growing up watching her mother do the Tibetan rite of the "Fountain of Youth" at each sunrise to undergoing rigorous 200-hour teacher training, it was a natural path for her to choose athleisure gear. Apart from cutting up, sewing and creating new styles of clothing as a child, Utan hadn't thought of a career in fashion. She had studied business management at Koç University, but life led her back here.

She started paying attention to the way the whole body opens up, stretches, elongates and breathes during yoga. She focused on how her clothes felt against her skin.

"Good yoga attire should make you feel free, not limit your body's movements. If your tights or bustier limit your movements, squeeze, dig in or cause discomfort, it is not right to do yoga in that outfit. In my opinion, you have to forget that you are wearing clothes while doing yoga. It is not about how you look, but about how you feel," she explained. It wasn't too long after she saw the irony in covering your skin, the biggest organ in your body, in unbreathable fabrics like polyester and nylon while doing a mindfulness practice that aims to send oxygen to every cell.

With the clarity and perspective provided by her 13-year yoga practice, Utan then asked herself how she could help fix a small part of this disordered world and it made her realize how "We were harming nature first and ourselves second."

There are many brand founders and designers out there who don’t practice what they preach. Utan is not one of them.

She says especially over the last five years, whether through seeing with her own eyes the sad behind-the-scenes reality in clothing manufacturing or witnessing the planet suffer from climate change and pollution, her shopping habits have changed.

"I (now) stop and think and ask myself: Do I really need this?" The majority of the time, as for many of us, the answer is no. When she does actually need to buy something, she favors small businesses over chains and ethical over mass-produced. Of course, not all of us can strictly avoid fast fashion when economic privilege is involved, but Utan believes in doing the best you can.

"As Lando Studio, we work on timeless pieces that can be used across all seasons and (should) be in every woman's wardrobe," says Utan. Excessive consumption and seasonal trends were all an obstacle against her ethical production principle. She wanted no deception, no harm, no tearing each other down.

Besides being timeless and lasting for eons, for Utan, fashion and dressing should also be effortless.

“I think the clothes in which you feel the most natural and your very best is the best style," she says, adding "This, for me, is when people are respectful toward and in harmony with themselves first and their environment in close second."

When the first wave of the pandemic hit, Lando Studio was not of those brands that had a hard time finding their footing in the new normal of fashion. Having focused on yoga attire (read: comfy, form-fitting, work-from-home gear) the brand already produced seasonless and timeless designs.

“For us, in terms of our design calendar, nothing changed. We continued at our own (slow) pace.”

But Utan added: “Like everyone else, I started working from home. Video meetings and remote videos became the solution. We continued our clothing production and operations without interruption as much as we could. But admittedly, I have worked harder than ever.”

When the lines between office and home become as smudged as the lipstick you rebelliously wear under your face mask to perk yourself up a bit, there are few people in the world who can say the opposite. Wouldn’t you agree?

On the topic of work and new habits, Utan said the pandemic, as testing as it has been on relationships especially when you are a social butterfly like her, has helped her turn inwards instead.

“One thing this pandemic has taught me is self-discipline. I always knew its importance but now I can plan and discipline myself like I never did before.” Especially when you live in a 1-bedroom flat, she added, jokingly.

And on a more global level, Utan believes the pandemic has shown people how much they really need each other, and to stop, watch and think about what we’re doing to our home – to Mother Nature.

The biggest gripe Utan has about the industry’s current way of operating is how some brands are exploiting sustainability and using it as a cloak to cover up their unsustainable ways.

"It is being used purely as a marketing tool and strategy. ... This goes completely against the transparency demanded in the world of sustainability," she said. Call it wrongdoing or a scam, unfortunately, that's how major fast-fashion brands position sustainability these days in a complete clash of principles.

The key to turn this tragedy/irony in fashion is the new generation, Utan said.

"The next generation is growing up with a new-found and growing awareness that this situation is extremely ironic. Therefore, as more young people demand more transparency, all brands will improve their production processes in line with these demands. We have to realize our strength as consumers. Whatever we demand, the industry will supply it. Therefore, we must make conscious choices and develop (eco-)sensitive consumption habits."

Just like any revolution, to create an impact you need to get masses involved, from all walks of life and all professions.

"It will not be enough for brands to improve or to raise awareness among consumers. I think there is a need for global-scale projects in which the private sector, public sector, NGOs and all other collaborators can create a joint action plan. The United Nations Alliance for Sustainable Fashion and The Fashion Pact are good examples of this," explained Utan.

In that respect, she sees great potential in Turkey.

"We are already a big producer of organic cotton and export high-quality, eco-friendly baby clothing to Germany and other developed countries," she said, adding that as Turkey is already renowned in the textile industry, it won't be difficult to transition to a more respectful way of producing.

Utan, who was selected by the World Economic Forum (WEF) as a Global Shaper in 2016, believes it's only a matter of time, and collective effort, before Turkey can join the big green league and be known for shaping fashion in the right direction.