© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

Climate change and global warming mean rising sea levels, which in turn threaten coastal cities across the globe that will face a renewed struggle with the seas they harbor. Iconic New York is no exception, and the city has been taking preemptive precautions after major storms highlighted its weakness in the face of extreme weather and it is now erecting a system of walls and floodgates to protect it from rising waters at a cost of $1.45 billion.

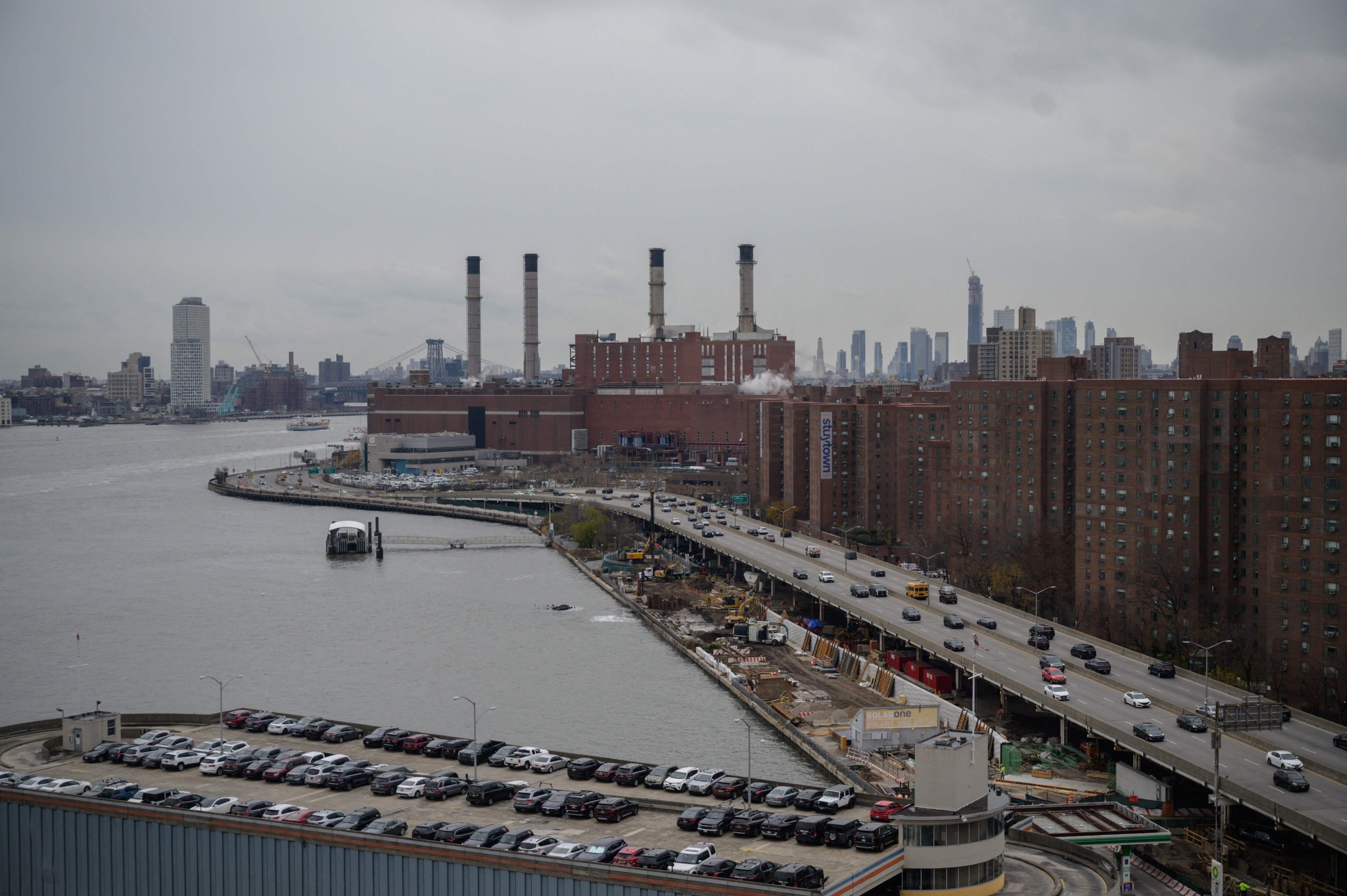

Hurricane Sandy, which hit the United States in 2012, was the reason for establishing the East Coast Resiliency Project (ESCR), running 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) along the shoreline of Lower Manhattan. Hurricane Ida, which ravaged parts of the city this year, added further urgency.

During Hurricane Sandy, which killed 44 people while impacting 110,000 more and leaving $19 billion in damages, water levels rose upwards to 8 feet (2.4 meters), according to Tom Foley, New York's acting design and construction commissioner.

The completed wall will reach as high as 5 meters (16.5 feet), Foley said. The project will also include gates to prevent water from seeping into Manhattan, home of the densest population in the U.S.

The wall between the 23rd and 20th streets is already constructed, an area where the East River and residential housing are at their most narrow.

Further down, where terrain allows, the project will include a hilly park that will serve as a protective wall, as well as a dock, an esplanade, bike lanes, benches and garden areas.

The city will also plant some 1,800 trees – nearly double the number that the project's construction has destroyed – along with an additional 1,000 in the neighborhood, said Sara Nielsen of the New York City Parks Department. Some 500 new trees have already been planted.

And a new underground drainage system will improve the sewage network's evacuation capacity, while the construction of a power substation should help prevent a dayslong power loss that happened during Sandy.

That major 2012 hurricane proved one of the worst to hit the U.S. this century, along with 2005's Katrina, which devastated New Orleans, and Harvey, which lashed Houston in 2017.

But the project is far from enough: New York's some 835 kilometers of coastline faces forecasts of more than a 2-foot rise in sea levels by 2050 and nearly 6 feet by the end of the century.

According to Jainey Bavishi, who directs the Mayor's Office of Climate Resilience, the city is investing in a "multi-layered strategy."

"We are building coastal protections where possible to keep the water out – but we also recognize that we're not going to be able to keep the water out in all places," Bavishi told Agence France-Presse (AFP).

She explained that the protections now under construction are "built to be adaptable."

"So if the projections for sea level rise and storm surge get worse than what we believe they are now, we can actually add elevation to the wall to add further protection."

Many buildings in Manhattan along with crucial infrastructure are also being reinforced, Bavishi explained, with construction limited in high-risk areas, and collaboration with residents and small businesses to minimize the impact of extreme weather events.

Some citizens are unhappy with the project and local associations have lodged appeals against it. Barring delays from those hurdles, the project is meant to be finished by 2026.

The hope is that Lower Manhattan will be able to breathe easier.

"I think it's a good idea but things move slowly, so I don't know how ... effective it's going to be," said one resident named Terry.

The ESCR is just one component of a larger project announced in 2013, when the city revealed a nearly $20 billion plan aimed at "climate resilience."

But that price tag is just a "down payment," Bavishi says. "Resiliency is a process, not an outcome."

The U.S. Congress recently approved a massive social spending plan of $1.2 trillion, which will allocate roughly $550 billion to climate and clean energy tax incentives.

"I do believe that our entire climate resiliency strategy is one of the most ambitious in the U.S. and potentially in the world," Bavishi said.