© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2025

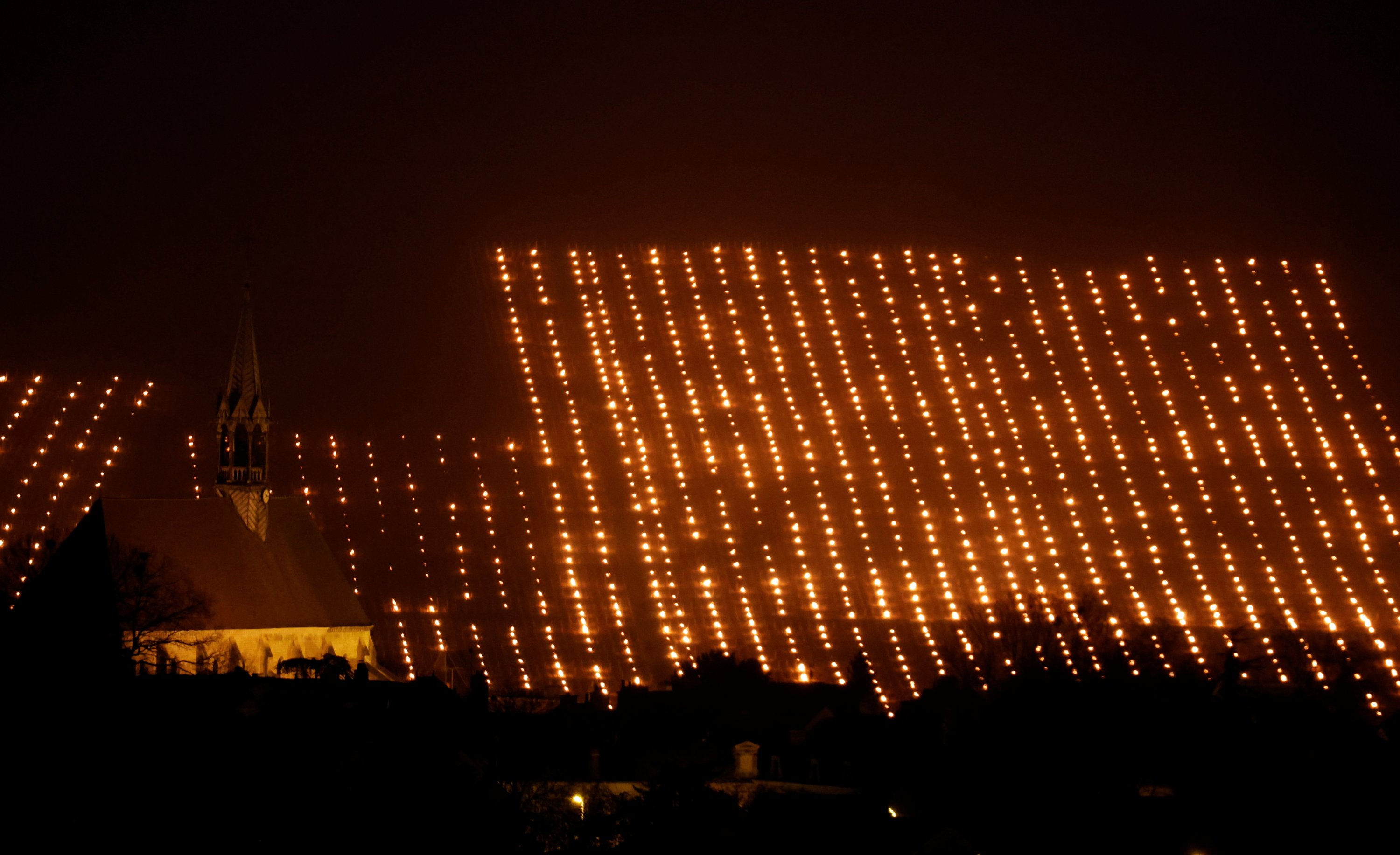

Scientists said Tuesday that climate change had sharply increased the odds of devastating events such as the frost that wiped out a third of French wine production at a cost of around 2 billion euros ($2.42 billion) in the space of a few nights in April. The frost blanketed the country's most well-known and prestigious wine-producing regions in what minister Julien Denormandie called "probably the greatest agricultural catastrophe of the beginning of the 21st century."

Scientists warned that climate change would raise the risk of such events even further in the future.

The findings are from World Weather Attribution, an international organization that analyzes the link between extreme weather events and global warming.

They looked at data from a zone covering vineyards in Burgundy, Champagne and the Loire valley and ran 132 climate model simulations.

The study concluded that a warmer climate has increased the probability of an extreme frost coinciding with a growing period by 60%.

And study co-author Robert Vautard of the Pierre-Simon Laplace Institute for climate and environmental science put the chances even higher than that.

With the goal of capping global warming at 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels likely out of reach, he said during an online press conference he expects "the likelihood of such an event to increase by an additional 40%."

April's plunging temperatures were particularly lethal because they followed a period of exceptionally mild weather in March that encouraged trees and vines to bud.

"Bud-break," when young leaves begin to unfurl to prepare for photosynthesis, makes vines vulnerable to deadly freezing temperatures.

Wine growers have always been wary of a late frost, but now they are being forced to redefine what they consider "late."

Budding is "happening earlier and earlier," said climate researcher and study co-author Nicolas Viovy, "it has moved up almost 15 days since 1980."

To analyze the likelihood of future devastating frosts, researchers had to take into account two consequences of warming: a decrease in freezing temps on the one hand and an earlier start to the growing period on the other.

"It is a real scientific step forward to be able to analyze composite events" like this one, said Samuel Morin who heads up a combined unit of the French National Research Institute (CNRS) and Meteo France, which contributed data and researchers to the report.

"You can't say of an isolated weather event 'it's because of climate change.' But you can measure the extent to which climate change affected the probability that such an event could occur," he told Agence France-Presse (AFP).

The fallout from April's frost was widespread with hundreds of thousands of hectares of crops and vines in 10 of France's 13 regions hit, affecting kiwis, apricots, apples, beets and rapeseed.

Markus Reichstein of the Max Planck Institute, another study co-author, pointed to the urgency of being able to anticipate the likelihood of such events.

"Economically it can be quite critical," he said during the press conference, adding that for wine growers "it could be an existential question."