© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

Faith and survival, not the machinery of death, are the central themes at an atypical Holocaust museum in Brooklyn.

The three-year-old Amud Aish Memorial Museum, located far from the tourist crowds at near the very edge of the borough, focuses on the experiences of Orthodox Jews during and after the Holocaust.

Its collection includes letters, diaries, photos and religious items, like a frayed prayer shawl worn secretly by a prisoner at Auschwitz.

Many were donated by Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Jews who had stashed the artifacts in basements and attics would not have given them to another museum, Amud Aish staffers said.

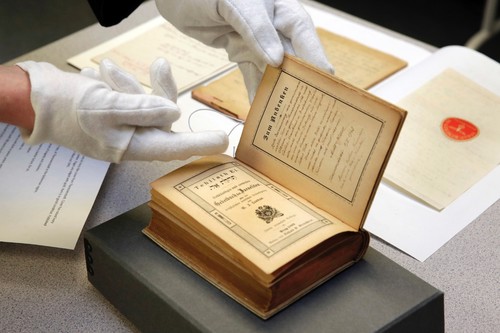

A 1893 prayer book in the museum's collection that was retrieved by a U.S. soldier from the Theresienstadt concentration camp in Czechoslovakia during World War II.

"Part of that is because their culture is different and they don't patronize museums for the most part," said Shoshana Greenwald, director of collections. "But here they felt this was a museum that would tell their story and understand where they are coming from."

The collection includes the Warsaw Ghetto diary of Hillel Seidman, who wrote about Jews' daily struggle to survive and to practice their religion in the face of horrific persecution.

"It's a well-known diary," said Dovid Reidel, the museum's director of research. "This is the original."

The family of Seidman, who survived the Holocaust and died in 1995, gave the diary to Amud Aish because they "felt other museums will just focus on his general story," Reidel said. "They felt he wouldn't be appreciated from his religious dimension as well."

Currently housed in a temporary space downstairs from a home health care company, far from city subway lines, the Amud Aish Memorial Museum has long planned on moving to a more prominent location. When it opened in the remote Mill Basin neighborhood, there were plans to build an $11 million permanent museum in the borough's Borough Park section, home to a huge and growing population of Orthodox Jews. Sholom Friedmann, the museum's director and CEO, said there's now no fixed date for a move.

An exhibit that officially opens at the museum later this month tells the little-known story of thousands of Jews who found refuge in Japanese-occupied Shanghai, China.

A group of teenage girls from a private Jewish school clustered around the vitrines during a recent visit and learned about the Walkin family, who fled Lithuania on the Trans-Siberian Railway in 1941, landing first in Kobe, Japan and then in Shanghai. Program coordinator Miryam Gordon pointed out sabbath candlesticks adorned with Chinese characters.

"Daily life continued," she said. "Children were born. People got married."

Reidel's own grandfather, Mike Tress, is featured in Amud Aish's collection for his work trying to secure passage for European Jews to the United States or another safe haven.

There are typed minutes of an Oct. 14, 1944, White House meeting between first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Tress and other rescue activists. They met on a Saturday when religious Jews are not supposed to travel or conduct business, Reidel noted, adding, "When it came to rescuing lives, that supersedes the not traveling or not holding these work meetings on shabbos."

Colleagues in Holocaust remembrance said there's a place for a museum that's devoted to the devout.

"The more opportunities there are to engage with Holocaust education, the better," said Elizabeth Kubany, a spokeswoman for the Museum of Jewish Heritage - A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, located in lower Manhattan.

Tova Rosenberg, the creator of the "Names, Not Numbers," a Holocaust oral history program, said Amud Aish shows the "spiritual resistance" of Jews who maintained their religion even in the concentration camps.

"They were going to keep their religious commandments no matter what," Rosenberg said. "And that isn't portrayed so much in other museums."

Michael Berenbaum, a Holocaust scholar who has served as a consultant to Amud Aish and other museums, said he hopes Amud Aish can reach its core community while also attracting a broader audience that may have little contact with the Orthodox beyond passing them on the street. "I would hope that lots of non-Jews, non-Orthodox Jews would come to see it in part as a bridge to understanding with these people they live adjacent to," he said.