© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2025

Scientists using sophisticated techniques to determine the age of bone fragments, teeth and artifacts unearthed in a Siberian cave have provided new insight into a mysterious extinct human species that may have been more advanced than previously known.

Research published on Wednesday shed light on the species called Denisovans, known only from scrappy remains from Denisova Cave in the foothills of the Altai Mountains in Russia.

While still enigmatic, they left a genetic mark on our species, Homo sapiens, particularly among indigenous populations in Papua New Guinea and Australia that retain a small but significant percentage of Denisovan DNA, evidence of past interbreeding between the species.

Fossils and DNA traces demonstrated Denisovans were present in the cave from at least 200,000 to 50,000 years ago, and Neanderthals, a closely related extinct human species, were present there between 200,000 and 80,000 years ago, the new research found. Stone tools indicated one or both species may have occupied the cave starting 300,000 years ago.

Scientists last year described a Denisova Cave bone fragment of a girl whose mother was a Neanderthal and father a Denisovan, evidence of interbreeding. The girl, nicknamed "Denny," lived around 100,000 years ago, the new research showed.

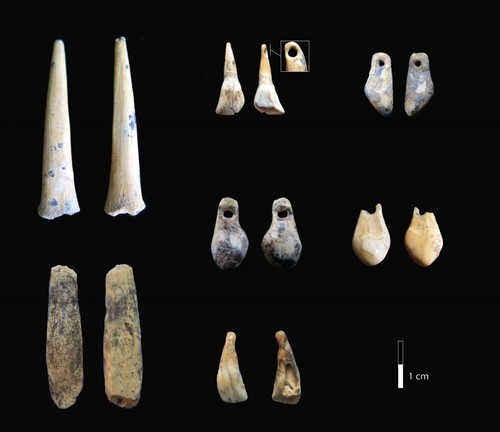

Pendants made of animal teeth and bone points from the cave were determined to be between 43,000 and 49,000 years old. They may have been crafted by Denisovans, suggesting a degree of intellectual sophistication.

"Traditionally these objects are associated in Western Europe with the expansion of our species, and are seen as hallmarks of behavioral modernity, but in this case Denisovans may be their authors," said archaeological scientist Katerina Douka of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany.

Our species arose in Africa roughly 300,000 years ago, later spreading worldwide. There is no evidence Homo sapiens had reached Denisova Cave when these objects were made.

Denisovans are known only from three teeth and one finger bone.

"New fossils would be especially welcome, as we know almost nothing about the physical appearance of Denisovans, aside from them having rather chunky teeth," said geochronologist Zenobia Jacobs of the University of Wollongong in Australia.

"Their DNA in modern Australian Aboriginal and New Guinean people tantalizingly suggests they may have been quite widespread in Asia, and possible even southeast Asia, but we need to find some hard evidence of their presence in these regions to flesh out the full story of the Denisovans," added University of Wollongong geochronologist Richard "Bert" Roberts.

The research was published in the journal Nature.