© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

Austria acts against Muslims almost every day because of their subconscious fear of Turks. Austrians have not forgotten the fear and their emperor's escape in the Battle of Vienna in 1683. When Turks were defeated in the Battle of Vienna, Europeans were so happy that everyone, including Germans, Polish, Croats and Armenians, believed that they contributed the most to this defeat.

Fatwa of fear

The relationship between the two countries became tense when Grand Vizier Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha started helping Emeric Thököly de Kesmark, the leader of Protestant Hungarians under the dominance of Austria. Austria did not want to start a war with the Ottomans. Count Albert de Caprara was sent to Istanbul as an ambassador to renew the Peace of Vasvar. The ambassador made great efforts to extend the duration of the deal. According to "Silahdar Tarihi," one of the most significant historical sources on 17th and 18th century Ottoman history written by Silahtar Findiklili Mehmed Aga, a fatwa indicated that the campaign was not permitted according to Islamic law.

However, the pasha did not give up the idea of campaigning against Austria, ignoring the fatwa. He brought letters of complaint about Austrian attacks from soldiers at the border and persuaded then Ottoman Sultan Mehmed IV to proceed with a military campaign against Austria.

The campaign on Vienna was settled in the autumn of 1682, and the Ottoman army marched to Edirne. When negotiations in December of that year did not show any results, the campaign was officially announced. On April 1, 1683, after the army spent the winter in Edirne, the Ottomans took action. Grand Vizier Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha mentioned the idea of attacking Vienna instead of Györ, which was the target given by the Sultan when he was in Szekesfehervar on June 25, 1683, for the first time. Only Crimean Khan Murad Giray and Budapest Governor İbrahim Pasha objected to the grand vizier's idea.

The Ottoman army marched to Vienna in 105 days. The Battle of Vienna was quick and successful. Considering that Suleiman I, known as Suleiman the Magnificent, reached Vienna on Sept. 27 and Mehmed III reached the Castle of Eger on Sept. 21, Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha led a very successful action in the beginning because the army reached Vienna on June 14, an early date.

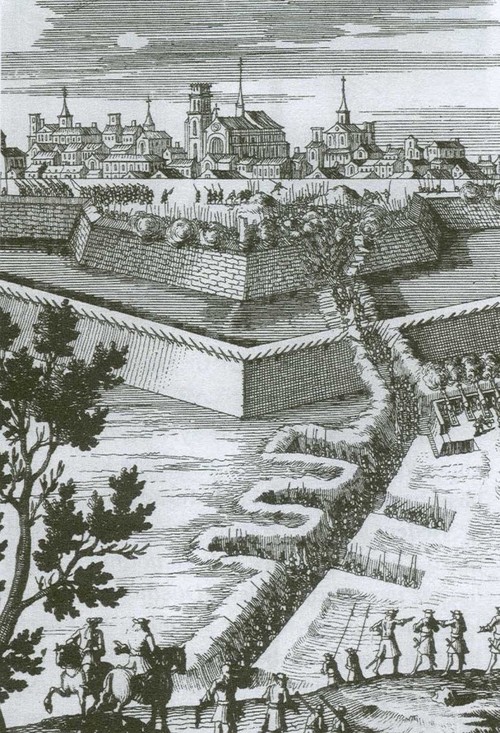

A drawing by an anonymous artist depicts the second siege of Vienna by the Ottoman Empire.

Emperor escaped

When the Ottoman army reached Györ, starting from Szekesfehervar, on July 1, fear in Vienna escalated. Emperor Leopold escaped from the city. After the vanguards of the Ottoman army reached the city on July 13, the army under Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha's command reached the city walls of Vienna with a four-hour walk on July 14. When the Viennese did not surrender, the siege started.

The number of defending Austrian soldiers decreased considerably after the two-month siege. As the siege continued, food became scarce, and illnesses such as dysentery broke out. Ottomans dug a tunnel in Vienna at five points close to the walls of the castle. If they were blown, the castle could fall.

Hopelessness in the city suddenly turned to joy when an army arrived to help on Sept. 11. Bells started to ring, and people cheered.

History changed in Vienna

Christian troops under John II Sobieski's command captured the hills to the northwest of Vienna without a fight. Preparing for war, the Ottoman army left the siege. On Sept. 12, the war started at Kahlenberg hill. The enemy gained the advantage because of tactical mistakes by Mustafa Pasha. When enemy troops started to enter the center of the Ottoman army, Kara Mustafa Pasha ordered the Turkish troops that had surrounded Vienna for two months to retreat to Buda. A historic period for the Ottoman military had come to an end.

The baker who saved Vienna

A statue of an Ottoman soldier holding a sword while sitting on a horse is at the corner where Strauch and Heidenschuss streets intersect in Vienna. This statue honors the memory of the baker who saved Vienna from Turks.

During the Battle of Vienna in 1683, the Ottoman army was using tunnels that are more effective method than gunfire for destroying city walls. Tunnels dug under the walls were filled with explosives. The explosives were detonated, and the walls were destroyed with the explosion. In the 17th century, defenders of city walls tried to understand whether a tunnel was dug, putting a bucket filled with water on the walls, to prevent such destruction.

Austrians prevented many Ottoman tunnels, after pinpointing their locations. In the last days of the siege, Ottoman tunnel diggers managed to dig a tunnel that reached the city walls without being discovered by the Austrians.

When they fired the explosives, the walls would be destroyed. A baker whose bakery was nearly 400 meters from the walls woke up early to make bread and cakes. When he was kneading dough, he heard noises from underground. He immediately told Austrian soldiers who dug another tunnel and exploded it before the Ottoman soldiers. Tens of Ottoman soldiers were martyrized in the tunnel. The baker's warning saved Vienna.

After the Ottoman army was defeated just outside Vienna, Austrian authorities rewarded those who contributed to the salvation of the city. One of the first awarded was the baker. The count of Starhemberg asked him what he wanted. The baker said that he wanted to make a cake using the crescent, the symbol of the Ottomans. The count accepted. Thus, the croissant, an unchanging piece of European breakfasts, was created.

First day of siege

On July 14, the first day of the siege, the city of Vienna almost fell before the Ottoman army. The Austrians set the city suburbs on fire to prevent their use in trench making by the Ottomans. However, the fire spread to one of the buildings around the Gate of Scots and eventually to the store where 1,800 tons of gunpowder were kept. If the gunpowder exploded, the city walls and much of the city would be destroyed. A great panic started among the people. A rumor that an Ottoman soldier had committed arson spread, and people beat whoever they saw in Hungarian clothes.

During the chaos, the wig of a young boy who tried to escape military service by wearing woman's clothes fell off. The public slaughtered him, thinking he was the traitor. As the panic continued, with the precautions of Captain Guido Wald Rüdiger, count of Starhemberg, who was the nephew of the commander of the castle, the fire was put out 40 steps from the gunpowder store.