© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

I wonder how many of the baby boomer generation of Turks really appreciate the contribution and legacy of the late Turgut Özal, the eighth president and 26th prime minister of the Republic of Turkey.

I also wonder how many of Turkey's millennials have heard of let alone are aware of the fact that the foundations of the current economic prosperity many of them have enjoyed since the onset of the new millennium and the 21st century in 2000, and the previous two decades, were laid by none other than Halil Turgut Özal, to mention his full birth name.

As we commemorate the 25th anniversary of his untimely and premature death at the relatively young age of 66 years in the official residence of the president, Çankaya Palace in Ankara on April 17, 1993, perhaps it is appropriate to reflect on his legacy, especially in the social, political and economic spheres at a time when Turkey once again is going through a game-changing phase of its republic history.

As a politician, Özal had a disarming charm, which stood with him well over time.

Özal was a thoroughly modern leader, in many respects ahead of his times. He died in fact on his exercise bicycle working out, initially thought of a heart attack but later investigated for foul play, including poisoning, which was left as an open verdict. Özal, of course, was the subject of an unsuccessful assassination attempt in 1988.

I do not think that the subsequent generations of Turks, whether in government, politics, business, banking, academia and society in general have fully acknowledged or appreciated the contribution and legacy of Özal, the larger-than-life character with a penchant for the avant-garde, to the evolution of the contemporary Turkish state, economy and society over the last four decades.

I had the pleasure of meeting Özal and his younger brother Yusuf Bozkurt, who was his economy minister at one stage, several times during the 1980s, the decade, which probably defined and set the course for Turkey's evolving democracy in a post military coup dispensation. I just happened to be in Istanbul during and immediately after the 1980 military coup staged by a junta led by Gen. Kenan Evren, covering an event thus experienced my first coup d'etat and curfew as a rookie journalist.

Hitherto, the West and the international media used to jest about the 10-year cycle of military coups in Turkey

Özal like any other politician had his flaws. But he was the most influential politician in the republic founded in the ashes of the Ottoman Empire and following the War of Independence, second only to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the "Father of the Nation." What Özal precipitated especially in the aftermath of the 1980 coup cannot be ignored. His training as an engineer and his spell at the World Bank made him more suited as a technocrat as opposed to being a born politician compared to some of his contemporaries - Süleyman Demirel, Bülent Ecevit and İsmet İnönü.

As such, his approach to politics was more pragmatic and practical, even on some of the contentious issues such as the rights of the country's Kurdish minority. "My grandmother was Kurdish," he used to stress. This pragmatism also lent itself in the way he dealt with Turkey's powerful and seemingly entrenched armed forces, erroneously self-promoted as the "Guardians of Turkish Democracy," when everybody knows that in a liberal democracy it is the parliament that is the guardian of the democratic process and the army that defends the borders and security of the nation.

"Dealing with the military has its limitations. You cannot demand this and that, you have to engage patiently and try to change the culture and mindset step-by-step," he told me in an interview. At that time the armed forces were like a "state within a state" complete with parallel education and business interests and exercised immense economic and financial power especially through a privileged position in procurement. The National Security Council, controlled by the Chief of Staff, trumped both military governments and subsequent civilian counterparts, until of course then-Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan started chipping away at the power of the army, eventually confining them to the barracks and firmly under the control of the civilian government.

Erdoğan owes much of these developments to the work started by Özal. I first met Özal when he served as the head of the Undersecretariat of the Treasury and later as deputy prime minister in the military regime of Bülent Ulusu in the immediate aftermath of the 1980 coup. A few years later he became prime minister in his own right as the leader of the ruling Motherland Party (ANAP). Those years were defined by what the generals and admirals called "guided democracy" - guided of course by the military, which seemed incapable of distinguishing it from the values and practices implicit in a liberal democracy. While Özal acquiesced to this process, it did play a crucial role in Turkey's transformation into a truer, albeit far from perfect, democracy.

Turkey in fact arguably has not experienced an outright military coup since 1980. But some 38 years later, some disaffected army faction, allegedly in cahoots with the Fethullah Gülen religious cult, did attempt to reverse this through a coup attempt in July 2016, but it failed miserably, leaving Erdoğan emerging as the new strongman of Turkish democratic politics.

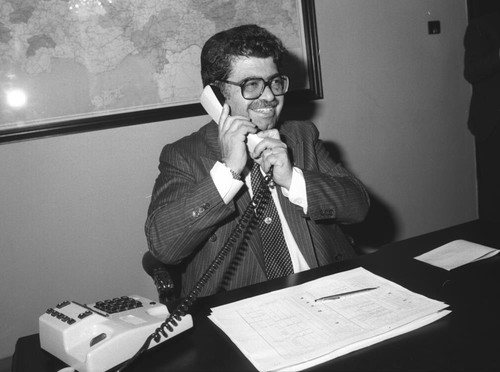

But as a politician, Özal had a disarming charm, which stood him well over time. I remember one particular meeting with Özal in the early 1980s, who was deputy prime minister at the time, and a keen proponent of the country's rapprochement with the Middle East and the Muslim countries.

As I was ushered by his aides to the top floor suite of the then-Etap Marmara Hotel, the ebullient and totally relaxed Özal went out of his way to make me feel at home.

He asked where I was from. I said I was from South Africa. He stressed that he had been to South Africa during his tenure as a World Bank official and was very impressed with the country, especially the Muslim community.

He then took me by the hand and led me into the sitting room. On the table, there was a huge plate of sweetmeats, "baklava," "lokum" and fruit. "First we eat and then we talk," he insisted. Well, I cannot reveal how much we ate. That is privileged information. But I can confirm that we had a very interesting discussion.

Özal talked about his vision of a Turkey straddling as a bridge between Asia and Europe - a modern and scientific Turkey. But he acknowledged that democratic institution building would be a challenge. He strongly believed that Islam is compatible with democracy and accountability, and that a Muslim country can also be modern, scientific and progressive.

But it is the above vision and his management of Turkey's economy in the 1980s that I think he would even

tually be remembered most for. Contrary to popular misconception, he was more influenced by Thatcherism than Reaganomics - the two dominant economic ideologies in play in the 80s - albeit it both on the monetarist center-right ideological spectrum. I used to think of him as "Turkey's Mrs. Thatcher," keen to roll back the reach of the state in economic management and let the market rule.

The one drawback of the Kemalist state was its overwhelming obsession with a centrally planned autocratic economy, where the state owned almost everything from restaurants, hotels and of course banks and industries - all operating highly inefficiently and being hotbeds of over-employment. I remember staying in state-owned hotels on press trips in Ankara and the old Maçka and Tarabya Hotels in Istanbul where there were more waiters than hotel guests.

Özal's free market instinct perhaps defined some of his greatest achievements - the opening up of the Turkish economy. At a stroke, capital controls were abolished - Turks could take out or bring in whatever declared foreign currency they wished. He also liberalized the foreign exchange regime and embarked on one of the most aggressive and ambitious export-driven policies anywhere in post-war history.

I remember wealthy Greeks making day trips to Istanbul to shop for "luxuries" including such banal items as imported brands of tea, which they could not buy in Athens.

The watchword of this campaign was "Export-or-Die" and did it work. Turkish contractors such as Kutlutaş, Enka, STFA and Tekfen, to name but a few, alone amassed $ 20 billion worth of contracts in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and Libyan markets in the 1980-1990 decade.

The other achievement was his unwavering support for the interest-free Islamic banking movement, which has since evolved into the participating banking industry, which in some areas such as small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) financing and gold-backed investment, Turkey is leading the world.

It was Özal's government who in 1983 introduced the decree 83/7506 regarding the Foundation, Operation and Liquidation of Special Finance Houses, that got the industry off the ground. The rest is history.

If there is anything Turkish President Erdoğan, who has just called for snap elections for June 24, can heed from his predecessor Özal's experiences, then it must be that politicians should have a sense of pragmatism, inclusiveness and where to draw the line. It is a pity that Turkey as a nation and society has yet to fully acknowledge the legacy of one of its bravest sons!

* Independent London-based journalist and economist