What everybody remembers about Der Stürmer was its morbid caricatures of Jews, the people who were facing widespread discrimination and persecution during the era. Its depictions endorsed all of the common stereotypes about Jews – a hook nose, lustful, greedy.

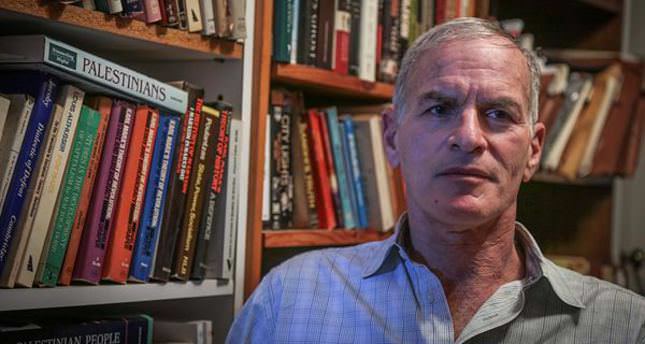

"Let's say, ... amidst all of this death and destruction, two young Jews barged into the headquarters of the editorial offices of Der Stürmer, and they killed the staff for having humiliated them, degraded them, demeaned them, insulted them," queried Norman Finkelstein, a professor of political science and author of numerous books including "The Holocaust Industry" and "Method and Madness."

"How would I react to that," said Finkelstein, who is the son of Holocaust survivor parents. Finkelstein was drawing an analogy between a hypothetical attack on the German newspaper and the deadly January 7 attack at the Paris headquarters of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo that left 12 people dead, including its editor and prominent cartoonists.

The weekly is known for printing controversial material, including derogatory cartoons about the Prophet Muhammad in 2006 and 2012. The attack sparked a global massive outcry, with millions in France and across the world taking to the streets to support freedom of the press behind the rallying cry of "Je suis Charlie," or "I am Charlie."

What the Charlie Hebdo caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad achieved was "not satire," and what they provoked was not "ideas," Finkelstein said. Satire is when one directs it either at oneself, causes his or her people to think twice about what they are doing and saying, or directs it at people who have power and privilege, he said.

"But when somebody is down and out, desperate, destitute, when you mock them, when you mock a homeless person, that is not satire," Finkelstein said. "That is, I give you the word, sadism. There's a very big difference between satire and sadism. Charlie Hebdo is sadism. It's not satire." The "desperate and despised people" of today are Muslims, he said, considering the number of Muslim countries racked by death and destruction as in the case of Syria, Iraq, Gaza, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Yemen.

"So, two despairing and desperate young men act out their despair and desperation against this political pornography no different than Der Stürmer, who in the midst of all of this death and destruction decides it's somehow noble to degrade, demean, humiliate and insult the people. I'm sorry. Maybe it is very politically incorrect. I have no sympathy for [the staff of Charlie Hebdo]. Should they have been killed? Of course not. But of course, Streicher shouldn't have been hung. I don't hear that from many people," said Finkelstein. Streicher was among those who stood trial on charges at Nürnberg, following World War II. He was hung for those cartoons.

Finkelstein said some might argue that they have the right to mock even desperate and destitute people, and they probably have this right, he said, "But you also have the right to say 'I don't want to put it in my magazine ... When you put it in, you are taking responsibility for it." Finkelstein compared the controversial Charlie Hebdo caricatures to the "fighting words," doctrine, a category of speech penalized under American jurisprudence.

The doctrine refers to certain words that would likely cause the person to whom they are directed, to commit an act of violence. They are a category of speech unprotected by the First Amendment. "You are not allowed to utter fighting words, because they are equivalent to a smack to the face and it is asking for trouble," Finkelstein said.

"So, are the Charlie Hebdo caricatures the equivalent of fighting words? They call it satire. That is not satire. It is just epithets. There is nothing funny about it. If you find it funny, depicting Jews in big lips and (a) hook nose is also funny." Finkelstein pointed to the contradictions in the Western world's perception of the freedom of the press by giving the example of the pornographic magazine Hustler, whose publisher, Larry Flynt, was shot and left paralyzed in 1978 by a white supremacist serial killer for printing a cartoon depicting interracial sex.

"I don't remember everyone celebrating 'We are Larry Flynt' or 'We are Hustler,'" he said. "Should he have been attacked? Of course not. But nobody suddenly turned this into a political principle of one side or the other."

Norman Gary Finkelstein, born in 1953, is an American political scientist, activist, professor, and author. His primary fields of research are the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and the politics of the Holocaust.