© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

The first hydrocarbon discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean were announced nearly 10 years ago with great excitement by regional players ambitious to avail lucrative energy exports. These regional countries, including Israel, Egypt and Greek Cyprus, were also on the radar of international actors aspiring to decrease their dependency on a dominant energy producer that sporadically uses its rich resource as political leverage over its buyers.

Yet, hopes were complicated by rising disputes over maritime borders, a spillover effect of the Arab Spring that ignited a still-ongoing war in Syria and the increased militarization in the region. Seldom anywhere else in the world, but in the Eastern Mediterranean, have energy resources and their share been subjected to so many years of unresolved disputes coupled with uncertainties emanating from a protracted war with overarching consequences in the region and beyond. The geopolitical factor of energy – an element experts and policymakers describe as a guarantee for connection and collaborative dynamic in the long term – has so far proved otherwise when it comes to the Eastern Mediterranean.

Hydrocarbon finds and demarcation disputes

The Texas-based petroleum and natural gas exploration and production company Noble Energy and Israeli conglomerate Delek Group disclosed the first large-scale hydrocarbon discovery in the Tamar field, located 80 kilometers west of Haifa, in 2009. Tamar is estimated to hold 280 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas. Shortly after in 2010, the American-Israeli duo announced the largest gas find in the Eastern Mediterranean in the Leviathan field –projected to harbor 540 bcm of gas. These two gas finds created hype and were hailed by many as a game changer and enabled Israel to move toward its ambition to become an energy exporter.

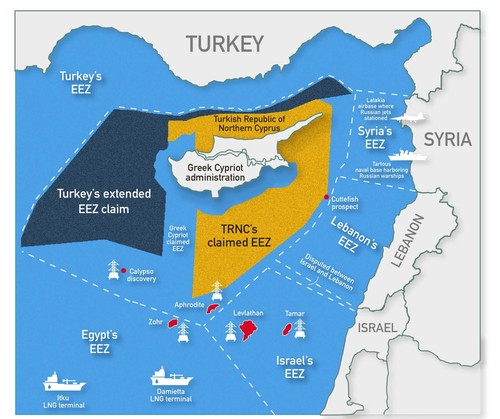

During explorations in 2011, the Noble-Delek duo also reported gas finds in the putative exclusive economic zone (EEZ) –the unilaterally declared area. The Aphrodite field, estimated to harbor 128 bcm of gas, has so far seen no progress regarding the commercialization of the resources because of the 40-year long conflict between Turkey-backed Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) and the Greek Cypriot administration. Turkey and the TRNC contest the unilateral claims of the Greek Cypriot administration and do not recognize the maritime border delimitation agreements signed with Egypt, Lebanon and Israel. The Turkish side views the waters on which the Greek Cypriots lay claim as disputed because they are overlapping with the continental shelf of the Turkish Republic.

Ankara argues that some of the blocks – particularly Block 4, 5, 6, and 7– on which the Greek Cypriot has commissioned international energy companies like the Italian ENI and French Total for explorations violate the country's 200-mile continental shelf as well as the 14-mile territorial waters of the Turkish Cypriot, which has been excluded from exploration efforts by the Greek administration in the south of the Cyprus island. Turkey and Turkish Cypriots vouch for an equitable share of the resources in the respective region, which is conditioned upon the peace progress in the island.

Since Greek Cypriots have limited options to export their gas to Europe – vying for reducing dependence on Russian gas– it has to work with Turkey, because selling the gas via a pipeline passing through Crete and Greece or liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals in Egypt, remains highly costly and politically challenged due to demarcation agreements. Turkey is also likely to oppose any pipeline project that might pass through its exclusive economic zone in the region.

With a view of protecting its own interests and the rights of the Turkish Cypriots, Turkey has been present in the region with seismic survey vessels and drillships.

The country's seismic vessel Barbaros Hayreddin has been conducting surveys in the region since 2013 after the two sides signed an agreement that gives Turkey exploration rights for 30 years in 2011. Its first drillship Fatih also started operations with deep-sea well-drilling in October 2018 off Alanya, a district in the Mediterranean province of Antalya. Later, Turkey also started shallow well-drilling in Mersin, another Mediterranean province. The energy ministry is now expecting the second drillship to arrive in the Turkish waters soon.

In February 2018, Turkey blockaded Italian firm ENI's rigging operations in the disputed Mediterranean waters by sending its military ships before the Italian company started rigging operations in the blocks unilaterally declared by the Greek Cypriot administration.

For the settlement of the dispute in the Eastern Mediterranean island, Turkey has been one of the three guarantor states, together with Britain and Greece, since the establishment of the Republic of Cyprus in 1960. The island of Cyprus has been divided into a Turkish Cypriot state in the north and a Greek Cypriot administration in the south since the 1974 military coup followed by violence against the island's Turkish people, and Turkey's intervention as a guarantor power.

Negotiations over Cyprus resumed after the 2004 U.N.-backed Annan Plan to reunify the Turkish and Greek communities. Another round of reunification talks – brokered by U.N. Special Cyprus Envoy Espen Barth Eide – was launched in May 2015 to discuss a permanent settlement for the divided island. The latest failed initiative took place in Crans-Montana, Switzerland in July 2017 under the auspices of guarantor countries Turkey, Greece and the U.K., collapsing early 2018.

The major actors involved in the conflict – Turkey, TRNC and Cyprus – have most of the time been advised to set up a joint mechanism to utilize the energy resources.

"In order to fully exploit the gas potential of the region and develop a regional gas market for the benefit of all, technical and economic cooperation through dialogue is a must," Sohbet Karbuz, Director of Hydrocarbons at the Paris-based Mediterranean Observatory for Energy (OME), told Daily Sabah, suggesting that natural gas is a common denominator among the countries in the Eastern Mediterranean.

"The prospects for the reunification of the island are dim for the near future. Until settlement talks resume, it would be wise to launch a separate dialogue between the Greek and Turkish Cypriots," David Koranyi, Eurasian Energy Futures Initiative Director at the Atlantic Council, told Daily Sabah in an exclusive exchange.

Koranyi, in the same vein as Karbuz, argued that the energy dialogue should be considered a way to craft a joint path to exploit energy resources to benefit both communities.

The prolonged conflict in the Mediterranean island is not the only source of continuous disagreement with regards to the share and commercialization of hydrocarbon resources. The failure of Israel and Lebanon to agree on maritime borders complicates gas exploration in the region. Last year, Israel castigated the Lebanese government's decision to launch an exploration tender in disputed waters.

The Israel-Lebanon maritime demarcation dispute unraveled in 2010 when they first inked a delimitation agreement since the points designated in the Cypriot-Israeli agreement overlap the Lebanese EEZ.

While Lebanon denounced the Israeli-Cyprus agreement, it had signed a maritime border deal with Cyprus back in 2007, which was never ratified by the Lebanese Parliament. However, Beirut maintains that an 850-square-kilometer area in the Leviathan creeps into its EEZ – a claim Israel iteratively rejects. This dispute momentarily exacerbated the tensions between Hezbollah and Israel, as the former threatened to strike the latter's offshore platforms.

In order to reduce the conflict over resources in the Eastern Mediterranean, "It is critical to reengage on Cyprus to facilitate a dedicated dialogue between the Greek and Turkish Cypriots over the development of energy resources and renew efforts to reach a settlement of the Israeli-Lebanese maritime delimitation dispute," Koranyi said.

"Renewed efforts to push for a maritime delimitation deal between Israel and Lebanon are essential. Given the political environment and relations of the two nations as well the current dynamics in the wider region, an actual agreement does not seem plausible any time soon," he added.

Thorny altercations among regional states render the monetization of the hydrocarbon resources a toilsome task. Some regional countries have made efforts on gas trade. For instance, Israel announced last week during the first East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF) in the Egyptian capital that it will export gas to Egypt and in October 2018, Cairo made a deal with Amman to sell its gas to Jordan via a pipeline through Sinai.

The first EMGF meeting in Cairo was held two weeks ago with the participation of energy ministers from Greece, Italy, Cyprus, Egypt, Jordan, Israel and Palestine. Turkey and Lebanon were the two regional countries that did not attend the forum.

In reference to gas trade agreements between Egypt, Israel and Jordan, Karbuz said that whether this will also be the case for exporting gas from the region to distant markets is yet to be seen. Harboring the largest gas field in the region with 850 bcm in the Zohr field, Egypt aims to boost regional economic prospects but its ambitions are currently crippled by domestic market dynamics and lack of developed infrastructure connectivity along with geopolitical concerns.

The current geopolitical dynamics leave Israeli developers with the least bad option, "delivering gas to Egypt to be turned into LNG exports at the Idku and Damietta facilities," John Roberts, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and energy specialist said.

However, "Egypt is likely to set tough terms for such processing and may insist on some of the gas being made available for use on the domestic market at relatively low prices," he added. To explain the political constraints of the monetization of the hydrocarbon resources in the region, Roberts stressed that political disputes hamper gas export options from Israel's Tamar and Leviathan fields.

"In purely economic terms, geographical proximity means that the most obvious local outlet should be the southern coast of Turkey, with its industries focused around Mersin and İskenderun and its need for energy to provide power for tourist resorts," Roberts added. Yet, he underscored, this option would require a pipeline – another difficulty, so long as the issue of Cyprus remains unresolved.

Another proposal to sell the Israeli gas in the international markets was through a Turkey-Israel pipeline, for which the two sides reached a preliminary agreement back in 2016 when a delegation from Israel visited Turkey. Turkish-Israeli attempts to build a pipeline could prove more profitable than Cyprus' proposed LNG plant because the direct costs are estimated lower. Several international and Turkish firms have already shown an interest in financing this project, the estimated cost of which is $5 billion, far more favorable than $15 billion for the LNG plant. However, even though the construction of a Turkish pipeline from the Leviathan field seems plausible, the conflict in the Cyprus island and the Israel's conflict with Lebanon and Syria does not warrant the project.

Syrian war and the naval competition

The already dispute-ridden Eastern Mediterranean has been subjected to further conflicts that continue to hinder the delimitation of economic zones and share of resources with the outbreak of the Syrian war in March 2011.

Global powers including the U.S., EU and Russia –having long-term interests in the region– have sought to ramp up their military existence in the area as the Syrian civil war has morphed into an international battleground, spilling over the wider region.

While the EU has sought to ensure its energy security by finding new resources with gas imports from the region with an East Med pipeline –Greece, Italy, the Greek Cypriot administration and Israel signed a preliminary deal in December 2017 to curb EU dependency on Russian gas– the U.S. and Russia have unwaveringly pursued their interests by signing gas exploration deals and expanding their military foothold in the region through naval and air bases as well as land forces.

To understand the Russian presence in the region, it is possible to ask the following question: Why would the world's largest gas producer, which has a proven reserve 10 times bigger than those found in the Eastern Mediterranean, want to get involved in the region? The answer to that question definitely requires thorough thinking.

During the Cold War, the Eastern Mediterranean was an area of racing interests between Russia and the U.S. In 1967, the Soviet Union formed the 5th Mediterranean Squadron to counterbalance the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the U.S. Navy's 6th Fleet. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia recalled the squadron in 1992 and left U.S. power unchallenged in the region.

Russia's 20-year absence in Mediterranean changed in May 2013, when Russian President Vladimir Putin announced a 16-ship Mediterranean task force, although it was mainly focused on the waters around Syria. The same year, Putin signed a 25-year agreement with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to explore the country's Block 2.

Two years later, in 2015, following the skirmish between Russian and Turkish planes, Moscow installed an S-400 SAM battery near Latakia, expanding its ability to monitor airspace over the Eastern Mediterranean. Russia's plans to expand the existing naval base at the port of Tartus was another example of Moscow's growing regional influence. All in all, the Syrian war and supporting the Bashar Assad regime gave Russia the opportunity to accomplish its centuries-long desire to reach warm waters.

In his study titled, "The prospect of Eastern Mediterranean gas production: An alternative energy supplier for the EU?" Pasquale de Micco, a European Commission expert, argued that Russia wants to dominate the Eastern Mediterranean gas market to protect its dominant position in Europe.

"The world's biggest natural gas producer is seeking exclusive rights to export LNG produced from fields off the East Mediterranean coast," de Micco wrote. A dominant position in the region, he suggested, would give Russia a major role in exporting Mediterranean gas to China, India and Japan where LNG prices remain more attractive.

With an ambition to pursue its interests and gain a foothold in the region, Russia had developed close ties with the Greek Cypriot government, Israel and Syria, striking deals with each. Experts like de Micco maintain that Russia's attempts portray its desire to fill the strategic vacuum left by the EU and the U.S.

Russia's involvement in the Syrian war and desire to safeguard its access to the gas resources in the region have also expanded the sphere of influence of Iran, though the alliance of the two countries in Syria has recently become dubious with diverging policies as Russia has recently reinforced relations with Israel. Iran's military bases, with some of them close to the Israeli border, and its reportedly present ships beyond Syrian shores are considered a source of threat to Israeli's national security and the security of its offshore activities in the Eastern Mediterranean.

"Into the Syrian vacuum, stepped Russia, Iran and Hezbollah, which led Israel to coordinate with Moscow and try to contain Iran and Hezbollah by using force," said Ehud Eiran, assistant professor of International Relations, in the School of Political Science at the University of Haifa and maintained that the U.S. is present in the region solely to fight Daesh since he considered the competition in Syria a drive for ensuring security.

After the end of the Cold War, the U.S. had downplayed its investment in the region until the 9/11 attacks and the invasion of Iraq in 2003. The Syrian war also provided a wider area of influence for key U.S. rivals in the region: Russia and Iran. While the U.S. feels the necessity to protect its own economic and security interest, it is also expected to shield the interests of its key allies like Israel.

In a briefing note on Syria, Turkey and the Eastern Mediterranean, Jon B. Alterman and Heather A. Conley from Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) elaborated on the U.S. interests in the region. Referring to the possible negative impacts of the Syrian war on U.S. interests in the region, Alterman and Conley suggested, "An unending civil war would spur greater regional destabilization, further weaken U.S. allies, and more deeply entrench the Iranian and Russian presence in the region." With a view of preserving the NATO cohesion and U.S. interests in the region, they recommended that the U.S. redesign its ties with Turkey and narrow down the gap between the objectives and interests of the two NATO allies.

Albeit an important trigger, the ongoing Syrian conflict is not the primary factor behind the expansion of Eastern Mediterranean navies and naval activity, Gabriel Mitchell, a policy fellow at the Israeli-based think tank Mitvim Institute and a Ph.D. candidate in Government & International Affairs at Virginia Tech University, told Daily Sabah.

"The two predominant factors are the diminution of the U.S. military –particularly the 6th Fleet– from the region, as well as offshore energy development. The reduced 6th Fleet has created a window of opportunity for actors like Russia and Iran, for example, to increase their presence in the region," Mitchell said. Other actors, including Turkey, Egypt, the Greek Cypriots, and Israel, seeking to expand their naval capacity in the region do not primarily aim to compensate for the absence of the U.S. Navy, but they strive for protecting their offshore interests from potential state and non-state threats, he argued.

The U.S. indeed has an interest in maximizing gains and minimizing risks associated with natural gas developments in the Eastern Mediterranean, de Micco wrote in his study. While Israel's security is one of the rivets of U.S. policy in the region, the country also seeks to promote EU energy security by diversification of resources in a bid to cripple Russian dominance. To accomplish this program, the U.S. conducted joint military exercises with Greece, Cyprus and Israel, simulating the defense of deep-water gas drilling installations in the region in 2012. It also sought a solution to maritime border disputes between Israel and Lebanon and to better relations between Turkey and Greek Cypriot administration. But Turkey and Lebanon lambasted U.S. engagement in drilling operations with its companies Noble Energy and Exxon in the past.

Regarding the Syrian crisis as part of a great competition in the Eastern Mediterranean, Cafer Talha Şeker, research fellow at the Association of Researchers on the Middle East and Africa, stressed that the geopolitical competition in the region is of great concern for U.S. national security and the country seeks to make Arab nations acknowledge Israel's role in the energy market to be designed in the Eastern Mediterranean. He also drew attention to the rivalries among the Western states whose companies have not been able to agree on the share of resources yet.

Along with the diplomatic disputes on the maritime borders, the Syrian conflict continues to hamper any energy development project in the Eastern Mediterranean with the involvement of numerous states, each earnest to safeguard its own interests. So long as the political and economic rivalry is complicated by military competition, the hydrocarbon resources in the region are doomed to remain unexploited.