© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

Who could have guessed 2017 would be the year of "Motherland Hotel"? For a long time, Yusuf Atılgan's 1973 novel has held a cult status among Turkish readers. Here was a text so unconventional, so radically innovative and so contrary to accustomed literary tastes, that there was something almost embarrassing about liking "Motherland Hotel" too much.

Even Oğuz Atay's similarly unusual 1972 novel, "Tutunamayanlar" (also out in an English edition this month - "The Disconnected" translated by Sevin Seydi) offers a safer, cozier, more identifiable world, telling stories of mostly upper middle class Turks with learned references to Shakespeare, Montaigne and Joyce. The world of "Motherland Hotel," meanwhile, is chilling, as far removed from Turkey's middle class sensibilities as one can imagine. This is a violent, cruel, ruthless world where we get a glimpse of the terrifying truths of the nation's collective psyche.

Even Oğuz Atay's similarly unusual 1972 novel, "Tutunamayanlar" (also out in an English edition this month - "The Disconnected" translated by Sevin Seydi) offers a safer, cozier, more identifiable world, telling stories of mostly upper middle class Turks with learned references to Shakespeare, Montaigne and Joyce. The world of "Motherland Hotel," meanwhile, is chilling, as far removed from Turkey's middle class sensibilities as one can imagine. This is a violent, cruel, ruthless world where we get a glimpse of the terrifying truths of the nation's collective psyche.

"Zeberjet [Zebercet in the original], the clerk at the Motherland Hotel, let himself into the room where on Thursday, three nights before, she had stayed-the woman off the delayed train from Ankara." Thus runs Fred Stark's rendering of Atılgan's opening sentence. This mysterious entry into an unsettling locale is followed by a set of small gestures: the turning of the key and Zeberjet's entry into her room and his movements inside. There, Atılgan gives us a little inventory of the room's objects: the quilt, the sheet, the slippers, the reading lamp, half-smoked cigarettes, and a "small dish with its five lumps of sugar."

Fans of Orhan Pamuk can find this passionate interest in objects somewhat familiar. "My heroes are Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar, Oğuz Atay, and Yusuf Atılgan," Pamuk has famously declared. "I have become a novelist by following their footsteps. I love Yusuf Atılgan; he manages to remain local although he benefits from Faulkner's works and the Western traditions."

In the Turkish Nobel-winner's most recent major work, "The Museum of Innocence," an obsessive man spends most of his life remembering, imagining, recounting and recreating details concerning his life with his beloved. We enter Zeberjet's mind with the knowledge of a similar absence. Atılgan opens a parenthesis about the issue of how many sugar lumps Zeberjet finds in the room, but then interrupts that narrative too, opening another parenthesis within it to communicate information about the woman's departure. Gradually the reader realizes how closely the language of the novel resembles Zeberjet's mind. Made of intersecting layers and lacking proper grammar, both are filled with moments of a somewhat gothic sense of beauty.

Atılgan, who had long worked as a translator for the book publishing branch of Milliyet and as a redactor for the publishing house Can, is among the ancestors of a set of modernist cultural figures in Turkey, including film director Ömer Kavur, a leading name of avant-garde Turkish cinema in the 1980s and 1990s. In his films "Akrebin Yolculuğu" (Journey of the Scorpion) and "Gizli Yüz" (The Hidden Face), (the latter of which was adapted from one of Pamuk's stories in "The Black Book") Kavur explored similar territory: mysterious Anatolian towns, the concept of time and being and the overwhelming sense of dread and despair.

Atılgan, who had long worked as a translator for the book publishing branch of Milliyet and as a redactor for the publishing house Can, is among the ancestors of a set of modernist cultural figures in Turkey, including film director Ömer Kavur, a leading name of avant-garde Turkish cinema in the 1980s and 1990s. In his films "Akrebin Yolculuğu" (Journey of the Scorpion) and "Gizli Yüz" (The Hidden Face), (the latter of which was adapted from one of Pamuk's stories in "The Black Book") Kavur explored similar territory: mysterious Anatolian towns, the concept of time and being and the overwhelming sense of dread and despair.

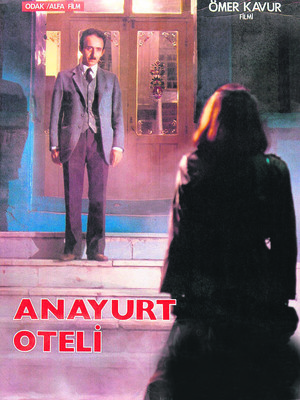

But it was with his 1987 adaptation of Atılgan's novel that Kavur truly came into his own. His masterpiece, a restored version of which will be screened this Tuesday at the Atlas Theater as part of the Istanbul Film Festival, offers a decisively bleak picture of the human condition. Its Norman Bates-like protagonist remembers how the mysterious hotel had been built in 1839 as a konak (an Ottoman mansion) before being turned into a hotel in 1923. The Ottoman Edict of Reorganization, Tanzimat, was published in 1839, and 1923 of course marks the birth of the Turkish Republic. Does the Motherland Hotel represent Turkey's modernization efforts in the past century and a half?

But it was with his 1987 adaptation of Atılgan's novel that Kavur truly came into his own. His masterpiece, a restored version of which will be screened this Tuesday at the Atlas Theater as part of the Istanbul Film Festival, offers a decisively bleak picture of the human condition. Its Norman Bates-like protagonist remembers how the mysterious hotel had been built in 1839 as a konak (an Ottoman mansion) before being turned into a hotel in 1923. The Ottoman Edict of Reorganization, Tanzimat, was published in 1839, and 1923 of course marks the birth of the Turkish Republic. Does the Motherland Hotel represent Turkey's modernization efforts in the past century and a half?

Both Atılgan and Kavur focus on Zeberjet's confusion about time and explores his difficulties with telling fictions from truths. The protagonist's fragile state of mind is inscribed into the dark corridors and empty rooms of the hotel where we, too, quickly lose our sense of time. Zeberjet had been born and raised inside this hotel, and while he loses his grip on reality, forcing himself on the cleaning lady and trying to figure out whether he had been to the hairdresser's a few days ago, his sense of isolation becomes the viewer's own.

The essayist Alberto Manguel has called Atılgan's novel "a startling masterpiece, a perfect existential nightmare, the portrait of a soul lost on the threshold of an ever-postponed Eden." At that threshold, Zeberjet, arguably the most frustrated character in modernist Turkish literature, turns into an uneasy representative of our own anxieties.