© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

With the energy crunch putting extra pressure on Europe's plans for heating homes this winter, Berlin has taken a big step to both use extra electricity and keep its citizens warm: a huge insulated hot water tower.

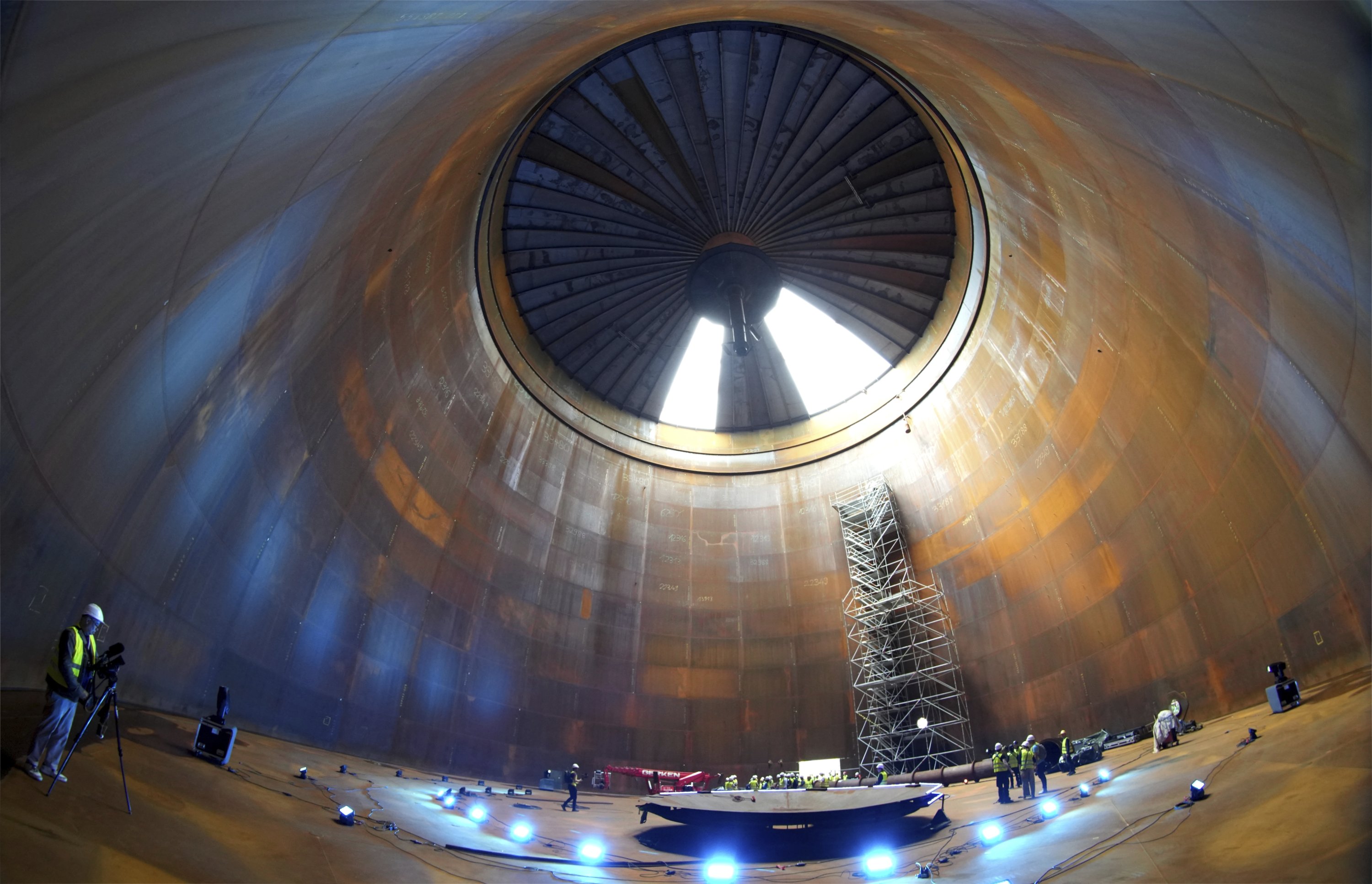

The rust-colored tower rising from an industrial site near the banks of Berlin's Spree River looks nothing like the sleek flasks Germans use for coffee, yet its purpose of providing some warmth throughout the day, especially when it's cold outside, is very similar to its tiny counterpart.

With a height of 45 meters (almost 150 feet) and holding up to 56 million liters (14.8 million gallons) of hot water, utility company Vattenfall says the tower will help heat Berlin homes this winter even if Russian gas supplies dry up.

"It's a huge thermos that helps us to store the heat when we don’t need it,” said Tanja Wielgoss, who heads the Sweden-based company's heat unit in Germany. "And then we can release it when we need to use it.”

While district heating systems fueled by coal, gas or waste have been around for more than a century, most aren't designed to store significant amounts of heat.

By contrast, the new facility unveiled Thursday at Vattenfall's Reuter power station will hold water brought to almost boiling temperature with excess electricity from solar and wind power plants across Germany.

"Sometimes you have an abundance of electricity in the grids that you cannot use anymore, and then you need to turn off the wind turbines,” said Wielgoss. "Where we are standing we can take in this electricity.”

The 50 million euro ($52 million) facility will have a thermal capacity of 200 megawatts – enough to meet much of Berlin's hot water needs during the summer and about 10% of what it requires in the winter. The vast, insulated tank can keep water hot for up to 13 hours, helping bridge short periods when there's little wind or sun.

It will also be able to use other sources of heat – such as that extracted from wastewater, said Wielgoss. While it will be Europe's biggest heat storage facility when it's completed at the end of this year, an even bigger one is already being planned in the Netherlands.

Berlin's top climate official, Bettina Jarasch, said the faster such heat storage systems are built, the better.

"Due to its geographic location the Berlin region is even more dependent on Russian fossil fuels than other parts of Germany," she told The Associated Press (AP). "That’s why we’re really in a hurry here.”

"The war in Ukraine and the energy crisis teach us that we need to be faster,” said Jarasch.

"First of all to become climate neutral," she said. "And secondly, to become independent.”

Wielgoss, meanwhile, is confident that Vattenfall's customers won't go cold this winter, despite the looming gas squeeze from Russia.

"Consumers in Germany are very well protected,” she said. "So they for sure will not suffer any shortages. But of course, we plead with everybody to really start saving energy.”

"Each kilowatt hour we save is good for the country,” she added.