© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

Turkish readers are often emphatic and prompt when praising the philosopher and novelist İhsan Oktay Anar. His characterful, narrative prose stylistically merges technical knowledge with artistic vision. He is celebrated for his special literary talents in Turkish, conveying its Eurasian subtleties with the finesse of a Seljuk archer, the heft of an Anatolian wrestler. And yet, according to the infamous 3 percent rule, referring to the proportion of translated books in English, only one novel by Anar is available to Anglophones, that being his sophomore work, "The Book of Devices." Titled like a classic Ottoman book, the work is full of eccentric characters moving through a bygone world that, while fictive enough to border on fantasy, retains the authentic charm of Istanbul's historic core.

He finished writing the skinny, 137-page novel on March 10, 1993, in verdant Karşıyaka, not far from where he taught philosophy until 2001 at Ege University in İzmir. The final inscription does not include the time of day. He placed it under a boldly capitalized "THE END," as closure for those left wanting more when the intertwining, darkly comic narratives conclude. Its point is unambiguous. While spinning with infinite curiosity through the contemporary medium of historical fiction, its trajectory echoes old-time traditions of Ottoman storytelling from the steaming, smoky cafes of its haunted past.

As a transcribed voice, the storyteller unravels his tongue when he speaks of the inconclusive lifespan, mysterious death and unknown burial of the lead protagonist. Under the pen of İhsan Oktay Anar, he is a man named Tall İhsan Effendi, the Minister of Devices, who wrote a microcosmic homunculus of the novel, also titled, "The Book of Devices." Effendi is the author's fictive double, an enigma survived by his work to compose, sketch and recount the manufacture of his many fantastical inventions, along with the worlds that inspired them and the personalities who saw them to realization. It is a clever literary device, a play of a play on words and names, potent for experimental writers who wish to relate the effect of mirrored plots and intersubjective voices reflecting each other with endlessly recurrent and kaleidoscopic, metaphysical depth.

A new leaf

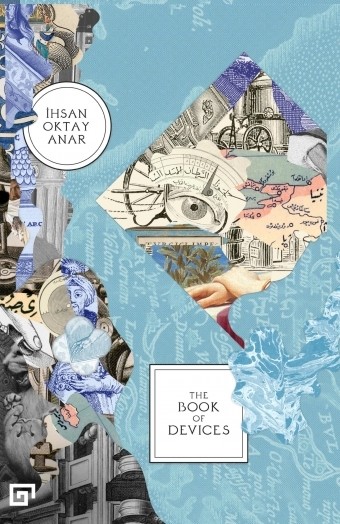

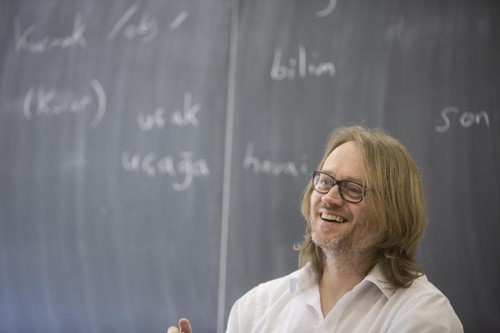

İletişim, a Turkish-language publisher in Istanbul, first sent "The Book of Devices" to the printing press in 1996. It became the second published novel by the then 30-something Anar, a prolific writer born in 1960. Gregory Key, a professor of Turkish language studies at Binghamton University, translated "The Book of Devices" in 2016 with support from the Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism TEDA Project (Translation and Publication Grant Program). Koç University Press printed it in June.

Gregory Key, a professor of Turkish at Binghamton University, translated "The Book of Devices" by Ihsan Oktay Anar in 2016.

A spill of Ebru seeps from the cover title, designed by E. S. Kibele Yarman like a collage from an antique stationery shop, with outmoded paper currencies commingling with cartographic drawings and architectural renderings. The three-chaptered book opens with a dedication to Anar's beloved parents before prepping the reader with a pair of epigraphs from the sacred texts of the Quran and the Bible that conjoin the sanctifying presence of King David to the ancient craft of metallurgy, exalting its pliability and strength.

After a peculiarly sharp typeface called Daubenton by Olivier Dolbeau, the action is set by a grisly group of caffeine-addled orators in a far-flung Anatolian coffeehouse, speaking of a long-dead gentleman native to Tophane, now a downtown confluence in Istanbul home to the national religious and secular divide, great socioeconomic diversity and the youngest generation of entrepreneurs in Turkey. His name was Yafes Chelebi, and about him issues some of the most animated and amusing prose fiction in all of translated Turkish literature. Despite being filtered through the relatively more rigidified English language, the writing of Anar leaps from his pages, dense with delicious gossip and salacious scandal.

The narration is candid, assuming the loud cadence of oral storytelling, a folkloric practice traditional to Turkish culture. Its informalities and airs of suspicion, conspiracy, intrigue lure minds by first dispelling rumors, to gain ears before parading into the heart of numerous, uninhibited yarns from the unchecked urban wilds of Ottoman Istanbul. And they are rich with references to life in the 19th century on the shores of the Bosporus, deeply researched though still playful, unweighed by obsession with fact, only suffused with the elements of style to tell more exacting, powerful tales. They all take place under the reign of Sultan Abdülaziz, a westward thinker who sought imperial progress on trips to European capitals like Paris, London and Vienna, while ruling his embattled, impoverished and shrinking lands from 1861 to 1876 when the Young Ottomans wrote the first constitution in Turkey.

The timeworn, weathered and beaten characters are manual laborers on the cusp of automated factory work, and Anar conjures them with a mental eye for early photography, capturing the poise of those fated to mostly unselfconscious and unexamined lives, without a thought to the vanities of public ostentation.

The manufacture of ideas

Anar distills the searing medieval spirit of the late Ottoman era, its amoral tone raised from opposite ends of the pre-modern, social spectrum, the heights and depths of its extremes from religion to industry. From the deadly edges of sword smithery to the rousing Anatolian battle prayers of old, it speaks of a time when Istanbul harbored a stripe of freedom only known and forgotten and enjoyed and suffered by those who emerged from shadow and smoke to sit among the tavern orators of the Fener and Galata districts, and the many countless districts of Greco-Italian tradition hailing from the long Byzantine night, its golden dusk faded, yet scoured by the proud descendants of the ancient immortality of New Rome.

There is a philosophical richness to the writing of Anar, even immersed in complex narrative logic, yet faithful to his irascible, colorful characters. Key's translation navigates the spiraling, Escher-like staircases of Anar's literary optical illusions with a refined ear for drama and absurdity. Ottoman society interpreted mechanical invention in more intuitive, eastern dimensions, one given to alchemy and magic. In contrast to the male-dominating Eurocentric drive to conquer nature, which has ever been the underlying scheme and modus operandi for Western industry and its tall orders, the Ottomans saw automation and its symphonies of metal fabrication as an opportunity to best meet the whims of the Sultan, whose quixotic desires were as capricious as the clashing currents of the Bosporus where it forks around the white boulder under the Maiden's Tower and into the Golden Horn and Sea of Marmara.

The style in which Anar's chronicle ensues in many ways reflects the overly elaborate detail of the devices themselves. For example, the very first of many drawings outlined in the book is of a sword, still hot from the burning iron, hanging in the shop of Yafes Chelebi for all to see after a long bout of hammering that conformed to a variety of Turkish musical rhythms like a tightly choreographed scene in a Broadway musical. Its blade doubles as a pair of scissors, streamlined into a newfangled, kinetic contraption. And in turn, Key's translation shows how Anar conversed with mixed vocabularies, pairing French and English expressions in a world ruled by the fusion sounds of the Ottoman Turkish language at the climax of its development, yet also on the cusp of extinction.