© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2025

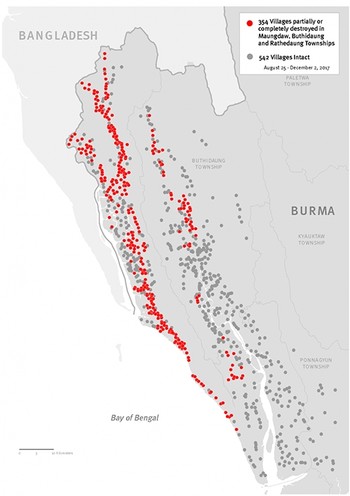

40 Rohingya villages in Myanmar's Rakhine State were burned in October and November, analysis of satellite imagery by Human Rights Watch said Monday, bringing the number of villages damaged since the military launched a violent crackdown against the Muslim minority in August to 354.

Dozens of Rohingya buildings were burned in the week of Nov. 25 as Myanmar signed a deal with Bangladesh to repatriate some 655,000 minority Rohingya who have fled what the U.N. said could amount to genocide, a statement released by Human Rights Watch said.

"The Burmese army's destruction of Rohingya villages within days of signing a refugee repatriation agreement with Bangladesh shows that commitments to safe returns were just a public relations stunt," Asia Director of Human Rights Watch, Brad Adams said, referring to Myanmar by its old name Burma, according to the statement.

At least 118 villages were damaged after Sept. 5, Human Rights Watch analysis shows, the date one-time democracy icon and Myanmar's de facto Aung San Suu Kyi claimed was the end of security operations sparked by Rohingya militant attacks on 30 police and military outposts on Aug. 25.

Meanwhile, the top U.N. human rights official has said he would not be surprised if a court one day ruled that acts of genocide had been committed against the Rohingya Muslim minority in Myanmar, according to a television interview to be shown on Monday.

U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad al-Hussein told the BBC that attacks on the Rohingya had been "well thought out and planned" and he had asked Aung San Suu Kyi to do more to stop the military action.".

"For us, it was clear... that these operations were organized and planned," he said in an interview on the crackdown estimated to have killed thousands and forced more than 655,000 Rohingya to flee to neighboring Bangladesh since August.

"You couldn't exclude the possibility of acts of genocide... You cannot rule it out as having taken place or taking place."

Zeid has already called the campaign "a textbook example of ethnic cleansing" and asked rhetorically if anyone could rule out "elements of genocide", but his latest remarks put the case plainly, toughening his stance.

"The elements suggest you cannot rule out the possibility that acts of genocide have been committed," he said, according to excerpts of his interview provided in advance by the BBC.

"It's very hard to establish because the thresholds are high," he said. "But it wouldn't surprise me in the future if the court were to make such a finding on the basis of what we see."

Myanmar denies committing atrocities against the Rohingya and has previously rejected U.N. criticism for its "politicization and partiality". The Myanmar military says the crackdown is a legitimate counter-insurgency operation.

Zeid said Myanmar's "flippant" response to the serious concerns of the international community made him fear the current crisis "could just be the opening phases of something much worse".

He told the BBC he feared extremist groups could form in the huge refugee camps in Bangladesh and even launch attacks in Myanmar, perhaps targeting Buddhist temples there.

He did not say, in the excerpts provided, which court could prosecute suspected atrocities. Myanmar is not a member of the International Criminal Court, so referral to that court could be done only by the U.N. Security Council. But Myanmar's ally China could veto such a referral.

Humanitarian group Doctors Without Borders (MSF) last week released a report claiming at least 6,700 Rohingya had been killed in the violence including 700 children, based on surveys of refugees in Bangladesh.

Almost 870,000 Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh, including about 660,000 who arrived after Aug. 25, when alleged Rohingya militants attacked security posts and the Myanmar army launched a violent counter-offensive.

U.N. investigators have heard Rohingya testimony of a "consistent, methodical pattern of killings, torture, rape and arson."

Several rights groups said Myanmar army actions against Rohingya amounted to "crimes against humanity" and "ethnic cleansing."

Nobel peace laureate Suu Kyi's less than two-year old civilian government has faced heavy international criticism for its response to the crisis, though it has no control over the generals it has to share power with under Myanmar's transition after decades of military rule.

Myanmar's Rohingya population are denied citizenship, freedom of movement and access to healthcare and education in the country.

They are labeled "Bengali" by most of the Buddhist-majority country, including the government, to infer they are illegal interlopers from Bangladesh