© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

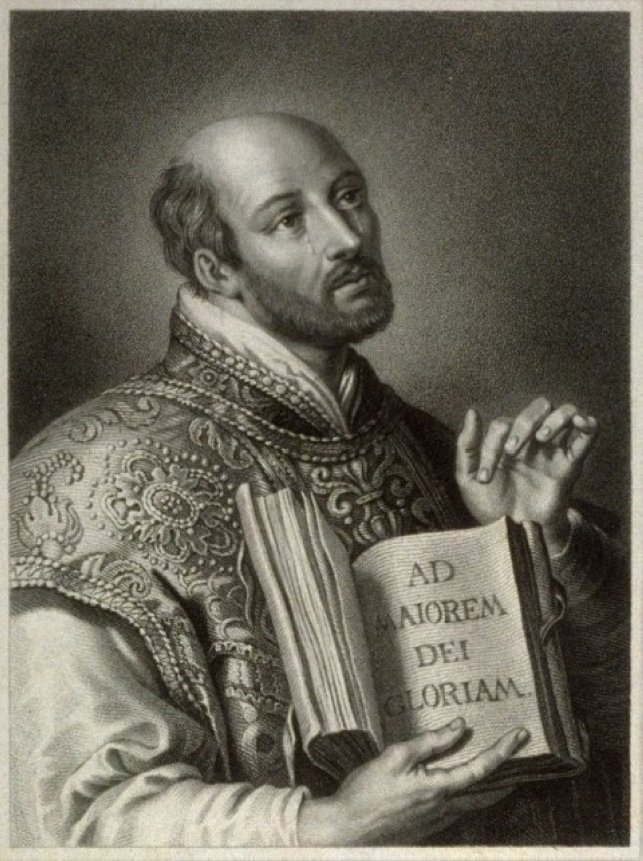

The Jesuit order, of which in our time Pope Francis is a member, started its activities on Sept. 27, 1540, under the name of the Society of Jesus, with the support of Venetian humanists. The symbol of the society is IHS ("Iesus Hominum Salvator" or "Jesus, Savior of Man"), and its motto is "Ad maiorem Dei gloriam" ("For the greater glory of God").

The society has a militaristic organization and regulations. At the head of the society is a general, or superior general, residing in Rome. This general is called the "Black Pope" because he wears a black cassock, in contrast to the pope who dresses in white. The Black Pope has a chief of staff, a secretary, a deputy general representing the society in the papacy and deputy ministers of the administrative parts made up of the provinces. The general is elected by the General Congregation, a council where the heads of each province gather, for life. Only the general is elected, as all officials at every other level are appointed by the general.

A year after the Society of Jesus was founded, Ignatius of Loyola was chosen as the order's first general. In the following years, Ignatius wrote the statutes of the society to guide his followers. According to this, obedience to superiors was essential in the sect: "(Jesuits) must allow themselves to act and be transported, under the divine direction of their superiors, like a corpse that does not interfere with its movement and control." Thus, in the Jesuit hierarchy, the general comes first, then God.

The Jesuits, like no sect before, established schools to take over nonreligious fields and started to train a large number of scientists, architects, craftspeople and merchants. Their schools were generally not just small buildings, rather they were large complexes consisting of classrooms, a theater, courtyard, observatory, church, printing house and residences. There was no fee for the students who studied here. Thus, they appealed not only to the children of the nobility but also to the gifted children of the common people.

Although other Christian orders did not accept it, the Jesuit order also opened its doors to Jews. Ignatius, who had very close relations with Jewish converts and the Alumbrados sects in Spain, ordered that the converts be allowed to join the Jesuit society. Jeronimo Nadal, Ignatius' absolute envoy, made this clear: "We (Jesuits) take pleasure in accepting those of the Jewish race." For this reason, the schools opened by the Society of Jesus were supported by Jewish bankers and merchants along with papal families such as the Borgia and Medici.

The society, which originally consisted of 10 members, had spread to 22 cities by 1549. The number of schools increased rapidly. The Jesuits were ready to go "among the Turks, or to the New World, or to the Lutherans, or to others, infidels or believers alike," by order of their general. Therefore, they opened schools not only in Spain and Italy but also in Brazil, India and Japan. Thanks to the colonies of Portugal and Spain, they became a global power by spreading to Asia and South America. When Ignatius died in Rome in 1556 at the age of 64, he left 35 schools behind.

The Jesuits were good at adapting themselves to the different cultures they encountered. They built their churches in accordance with the local architecture. They chose their clothes in accordance with the local attires. They learned the local religion and language very well. They instilled their beliefs in the people through the method of inculturation, using the local language and terminology. Raised with a humanistic background, they became Buddhists in Japan and Hindus in India. They came together with the local people of their location and participated in their rites.

The Jesuits carried out interfaith dialogue projects wherever they went. They achieved the greatest success in India. Through the priests they sent from their centers in the city of Goa, they influenced the Sultan of India, Akbar I, and his son Jahangir. They ensured that Akbar established a new religion, which was a mixture of all religions, called Din-i-Ilahi.

When the Jesuits celebrated their centennial in 1640, thanks to the money and manpower they had and the Machiavellian policy they followed, they become "Imperium in Imperia," or a "state within a state." In Europe, almost every Catholic king's private priest, that is, his confidant was from the Jesuit order. Jesuit teachers were raising the children of kings and aristocrats. The members of the sect had established an excellent intelligence network among themselves; they were spreading information from palaces and castles to each other.

The Jesuits also started trading under the pretext of supporting the expensive schools. They established their own sugar and cotton plantations in North and South America. Using their global network, they traded slaves, real estate, silver, fur, clothes, silk, tobacco, cocoa, spices, wine and jewelry all over the world. They formed partnerships with local companies. In many places, they had a monopoly. Moreover, they did not even pay taxes in many countries. They worked as bankers and financed wars. Thus, by the 18th century, they became the world's first "global company" in the modern sense.

The Jesuits were expelled from various countries dozens of times because of their religious and political intrigues but somehow they managed to come back. For example, after a student who graduated from the College de Clermont of the Jesuits plotted the assassination of King Henry IV of France, the Jesuits were expelled from Paris in 1595. But after a year and a half, they returned thanks to the pope's intercession. Again, the Jesuits, who came to Istanbul in 1609, were expelled from the city in 1628 because they were "seditious, inciting the people to rebellion." However, they returned only six months later, at the initiative of the French ambassador. The third General Francis Borgia had written to the members of the society as thus: "We entered as lambs, but we manage like wolves. We may be driven out like dogs, but we try again like eagles."

Finally in 1758, Portugal demanded the pope abolish the Jesuit order, accusing them of chasing power, gold and land, and betraying the church and the crown. Following this request, the king of Portugal was the target of an unsuccessful assassination attempt by a Jesuit. In the Catholic world, hatred of the cult reached its peak. All Jesuit property, real estate and movable goods in Portuguese-controlled lands were confiscated, and the Jesuits were expelled from Portugal and its colonies.

The next blow to the sect came from France. The stabbing of King Louis XV of France by a Jesuit in the courtyard of the Palace of Versailles in January of 1757 struck the sect like lightning. The last straw was the sect's failure to pay its debts to those it borrowed from. The Paris Parliament in 1762 and King Louis XV in 1764 announced their decision to ban the cult. The Jesuits, whose property was confiscated, were also expelled from France on the grounds that they were enemies of religion and morality.

In the Catholic world, the true face of the Jesuits was now revealed. The next step came from Spain. The members of the sect were expelled from the Spanish lands on Jan. 29, 1767, and their goods and companies were again confiscated. Spain was followed by the kingdoms of Naples and Parma. Raised by the Jesuits, Pope Clement XIII was watching the events silently and still defending the sect.

Under pressure from the Catholic world, finally, in February of 1769, the election for the new pope began, and three months later Clement XIV ascended the papal throne. At first, the new pope also did not want to touch the sect for fear of being poisoned. However, he could only withstand the insistence of the Catholic kings for four years. On July 21, 1773, by his order named Dominus ac Redemptor, the Jesuit order was banned throughout the Catholic world. A month later, papal officers and police stormed the Jesuit headquarters in Rome and detained the Jesuit General Lorenzo Ricci and his deputies. Ricci died two years later in the dungeon in Castel Sant'Angelo.

The Jesuits who fled from the Catholic world were embraced by the Protestant world. The Jesuits continued their activities in England and its colonies in North America. In fact, in 1789, under the leadership of Reverend John Carroll, they founded Georgetown Academy, which continues its life as Georgetown University, on the banks of the Potomac River on the Atlantic side of the United States. This was the first Catholic school established in North America.

"Enlightened" monarchs in Europe also opened their lands to the Jesuit order. King Frederick II, or Frederick the Great of Prussia, and Empress Catherine II, or Catherine the Great of Russia, left the order alone despite pressure and protests from the pope and Catholic kings.

Europe was shaken by the French Revolution, sparked by the Enlightenment, that broke out in 1789. The revolutionary army under Napoleon Bonaparte occupied Rome in 1796 and took the pope prisoner to France. Pope Pius VI died there. The Jesuit General Ricci, who had died in a dungeon, was thus avenged.

Pius VII, who was proclaimed the new pope in Venice in 1800, recognized the sect's presence in Russia the following year. Nevertheless, the French revolutionaries invaded Rome again in 1808 and took the pope prisoner and took him out of the city. It was only in 1814 that the pope was able to return to Rome, and he had to sign the Papal Ordinance allowing the Jesuit order to continue operations around the world that summer.