© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2025

James Joyce's novel "Ulysses" marks its 100-year anniversary with a reworking of the Greek myth that still retains the power to shock, confound and intrigue.

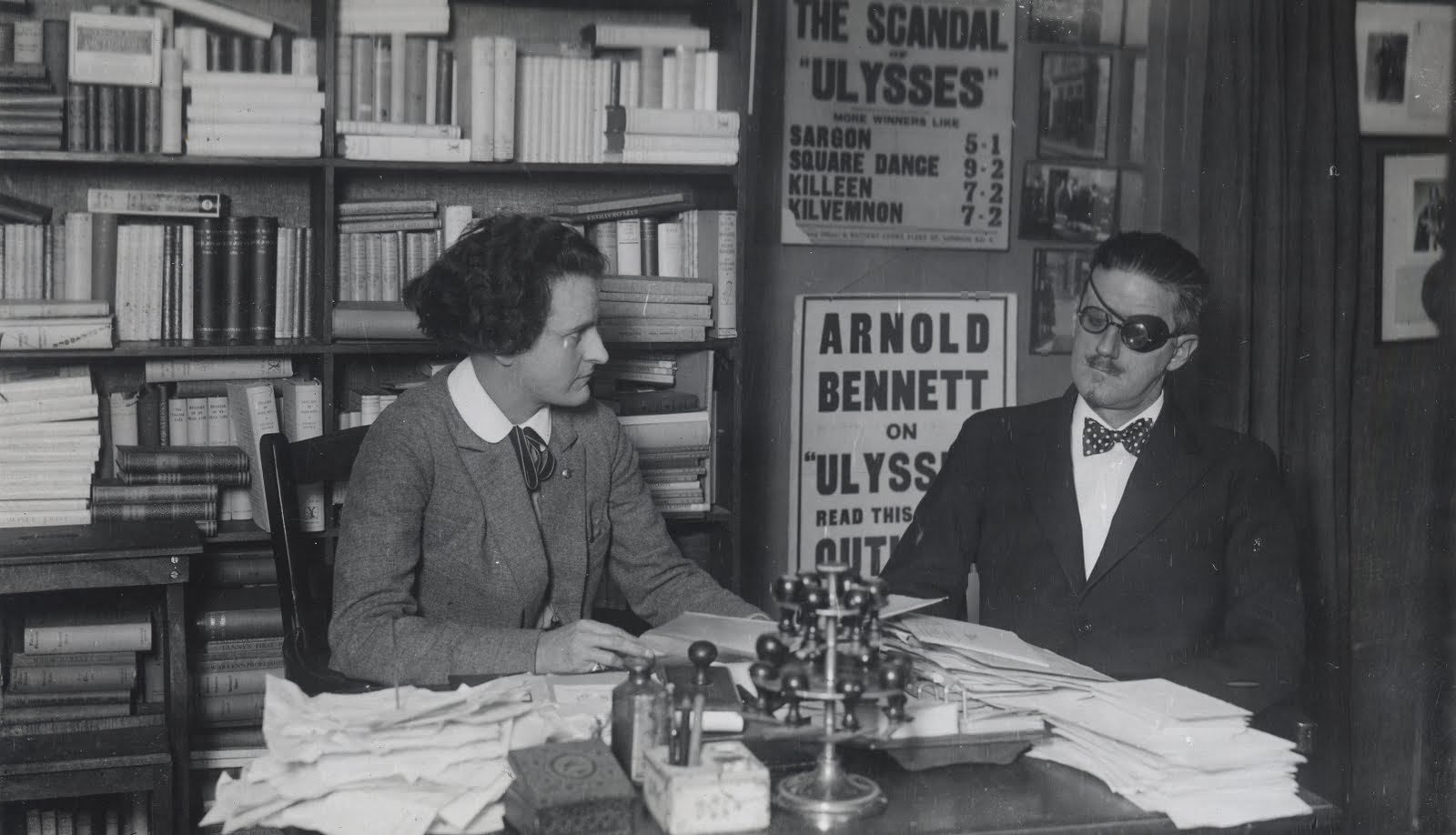

James Joyce's "Ulysses" was first published in February 1922 in Paris after printers in Britain had refused to handle the "obscene" novel. It remained banned there and in the United States for years.

The anniversary four months ago was duly observed by Joyceans around the world. But this week fans will don period dress to celebrate their annual commemoration of the novel with more than usual gusto.

"Ulysses" plays out entirely on one day – June 16, 1904 – and follows the emphatically unheroic Leopold Bloom around British-ruled Dublin, obliquely tracking the adventures of Homer's protagonist Odysseus on his epic return home from the Trojan War.

For "Bloomsday" this Thursday, performers in costumes from the turn of the 20th century - straw boater hats and bonnets – will reenact scenes from the book across the Irish capital.

Sweny's Pharmacy, where Bloom buys lemon soap for his wife Molly, will become a stage for reenactments of the book's "Lotus Eaters" scene, while a funeral procession for another character, Paddy Dignam, will be held in the city's Glasnevin Cemetery.

Events for the centenary have been held throughout Dublin this week.

On Tuesday an audience crammed into the first-floor room of a Napoleonic-era fort in Sandycove, where Joyce once stayed, to watch a performance of an imagined second meeting between the Irish author and his French contemporary Marcel Proust.

Now a museum and place of pilgrimage for "Ulysses" enthusiasts as the setting for the novel's opening scene, the two titans of 20th-century literature debate Joyce's legacy.

"It's just been fantastic to get down here and immerse ourselves in a bit of craic (fun)," Tom Fitzgerald, a volunteer with the museum who played Joyce in the performance, told Agence France-Presse (AFP).

"Some people take it very seriously. I always say at Sandycove we do the eating, drinking, and singing part of 'Ulysses' and if Joyce was around, he'd be here. He wouldn't be at some symposium."

Irish embassies around the globe will be marking the day with events including a Zulu performance of Molly Bloom's closing soliloquy in Johannesburg and a Vietnamese rendering of Joyce's "Dubliners" collection of short stories in Hanoi.

Elsewhere, grassroots festivals organized by fans in places ranging from Toronto to Melbourne and Shanghai are also taking place.

A totemic work of early 20th-century modernist literature, "Ulysses" is densely allusive and hard to categorize.

It dismantles genres as Joyce responds in revolutionary style to Irish nationalism, religious dogma and sexual politics, among a host of other themes.

Bloom himself is Jewish, an outsider in Catholic Ireland. The novel is sometimes smutty, sometimes scatological and impossible to decipher.

But it is often bitingly funny and never less than thought-provoking, as Joyce answers Homer with his modernist take on myth.

For Darina Gallagher, the director of James Joyce Centre in Dublin, "Ulysses," which was published in the same year as the Irish state was formed, raises questions that Ireland still contends with.

"We haven't been able to talk about gender and politics, identity and nationalism. And we're still only growing up as a society to confront issues of the Catholic Church that we can't believe Joyce is writing about," she said.

"Ulysses" was written in self-imposed exile away from Dublin as Joyce spent War War I on his own odyssey around Europe, from Trieste to Zurich and Paris.

The Bloomsday tributes carry a certain irony: Ireland, then in the grip of Catholic orthodoxy, refused to repatriate Joyce's body when he died in 1941, aged only 58. He was buried in Zurich.

British dramatist Tom Stoppard in his 1974 play "Travesties" imagines Joyce meeting Lenin and Dada founder Tristan Tzara in Zurich in 1917.

"What did you do in the Great War, Mr. Joyce?" a character asks the writer.

Joyce replies: "I wrote 'Ulysses.' What did you do?"