© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

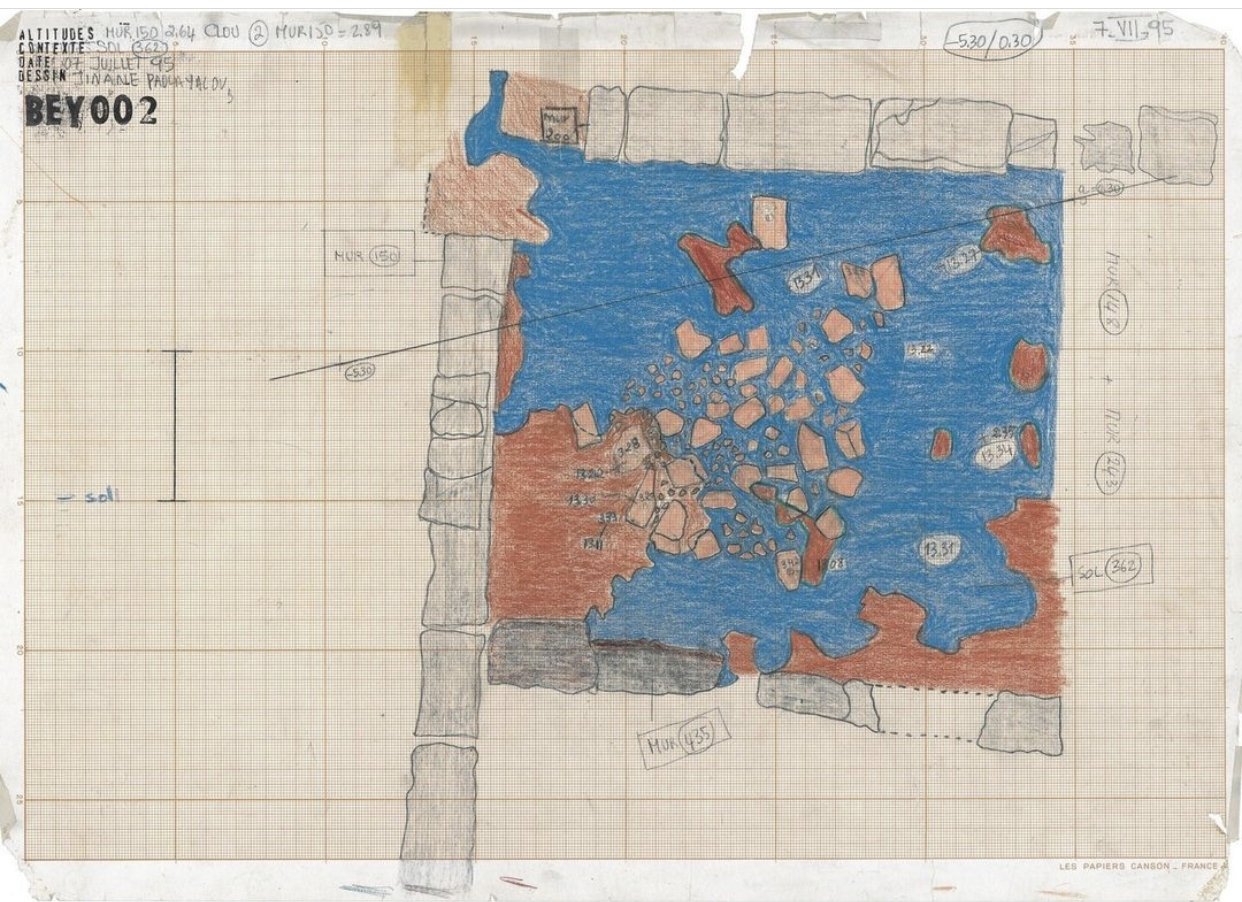

The centerpiece of “BEY002” by Paola Yacoub is a large-scale installation of a drawing that the artist made in 1995 at the Institut Français d'Archeologie du Proche-Orient (IFPO) BEY 002 excavation site. She transformed its likeness into a carpet surrounded by construction scaffolding. It takes up much of the opening section of the compact gallery space at DAADGalerie, a prestigious if modest haunt in Berlin’s postwar art scene. Its walls are covered with newspaper cutouts and supplementary drawings to their original scale, as well as a vitrine holding a number of documentary effects, before leading to a projector that clicks automatically, its light beaming against a wall with images from Beirut’s embattled, vulgarized core.

In collaboration with the historic Parisian tapestry manufacturer Manufacture nationale des Gobelins, “BEY2002” is a unique work of art: a carpet of a document color-coding Roman, Byzantine, and Hellenistic remains. In a text booklet accompanying the show at DAADGalerie, Yacoub provides ample context to her piece. Citing the scholarship of archaeologist Catherine Aubert, she explains that archaeological evidence points to a correspondence between the ancient Greek island of Delos and the early inhabitants of what is now the city of Beirut.

The tone of the show could be correlated with that of recent works by Turkish artist Barış Doğrusöz, whose multi-film installation “Locus of Power” opened SALT Galata’s 10-year anniversary programming “The Sequential.” His shrewd examination of archaeological perspectives in war-torn Syria, and their relativity to conflict, past and present, echoes Yacoub's perspective. In 1996, the public enjoyed a rare 10-day window in which they had the opportunity to bear direct witness to the BEY002 site. In turn, Yacoub reflected on the nature of excavating in the wake of the Lebanese Civil War as a layered, manifold process of destruction. She used the neologistic term, “archaeocalyptic,” to encompass the devastating force involved.

Such urban archaeological work cleanses the contemporaneity of an inner-city space, turning it back to its ancient roots. It is marked by a kind of indirect, often underhanded dialogue between living, local communities and with the overarching, current social reality of a metropolis and its national, or even international, integrity. An astute reader from Istanbul might remember the Haydarpaşa train station that since 2018 has become the grounds of archaeological studies, effectively stalling the general populous' hopes that its once-functioning train line will be renewed.

With reference to the thought of new realist Italian philosopher Maurizio Ferraris, Yacoub defends her document-carpet, reading into the idea that ruins are documents, and that modern people are tasked with becoming literate in them. They must not only understand what happened, but have a sense of shared responsibility for their preservation, or natural decay. Comparatively, the modernist Greek poets Constantine Cavafy and George Seferis became utterly famed and canonized in Western literature by foregrounding metaphors of broken columns and classical appreciation, themes that remain integral to the formation of historical identity.

And ruminating on the geopolitical trenches of the storm-cast region in which Lebanon and its material legacy are situated, much in the way that Doğrusöz did in the northern deserts of the Levant, Yacoub bemoans the persistent traffic of “blood antiquities” newly spurred by the fascistic art thieves of Lebanon. Yacoub's essay, “BEY 002, This is not a fiction, 2021,” comprises these phenomena by the term “metrukiyet,” a word once common to Turkish and Arabic meaning "abandonment." When the infamous port explosion brought a weakened Beirut to its knees on Aug. 4 last year, that withdrawal, that abandoning increased drastically.

Since that fated day, the earthbound foundations of Lebanon’s cultural precedent have become fainter as the crumbling of the reigning power structure fell squarely and unavoidably into everyone’s lap, its relics covered with fresh dirt. The debris of the modern city imploded into its own catastrophic and enigmatic history of ruins, fragmented alongside that of its predecessors’ once-treasured architectural, domestic and artistic roots. Yacoub wrote, dramatically, yet appropriately: “Our world has fallen apart. Transposing this document onto a carpet seems like a desperate gesture.”

But in true local fashion, Yacoub retained her sense of humor, that Middle Eastern affinity for survival through mockery and self-deprecation. “BEY002” includes a selection of newspaper clippings, full-page spreads tacked on the wall over the central installation that detail the caricatured responses that the educated class of news writers and critics stirred up amid the outright national collapse. She has a kindred spirit with the cartoonist Boo, who, in one piece that she featured illustrated a building in crisis. Flames encircle its ground floor, and on its rooftop business owners walk on M.C. Escher-like stairs.

The terrifying and the banal blend in Boo’s building in crisis is a microcosm of Lebanon as a whole where on one floor people are smoking and chatting benignly, while just below them, refugees are fleeing on airborne tethers. Above them, the military patrols, and the whole place is for sale. That dualism is likened to Yacoub’s mentioning of midcentury author Jean Paulhan, who wrote about the interchangeability of maintenance and terror. His work of literary criticism, “The Flowers of Tarbes, or Terror in Literature” (1941), forwards pioneering discourse on the role of art in politics and society.

On the one hand, intervention is necessary for the upkeep or spring cleaning of multiuse public space, demonstrating the very notion of urbanization as the overlap of multigenerational inhabitance alongside constructs of globalized commerce and cultural expression. But when done forcibly, acts of historical conservation assume the qualities of terror, perhaps like in jungles and rainforests, which, when distraught by the compulsion to save endangered species, then confront human communities who have subsisted and continue to rely on the harvest of their traditional ecosystems, including otherwise protected animals.

Through various media, images, text or both, Yacoub tells the story of her birthplace of Beirut with one eye closed so that she might focus in, more closely than others, at subjects that might have gone unnoticed by a more Orientalist gaze. Hers is a keen eye for the intellectual bridge that, unbroken, binds Lebanon to the soul of Western art. This is clear in her piece titled “Elagabalus” (2021), which is a collection of Roman coins gleaned from the excavation site that she drew and remade into the carpet. These objects point to the story of a self-destructive emperor, immortalized by playwright Antonin Artaud.

In his 1979 book about the anarchist ruler, Artaud wrote: “But there are stones which are alive, just like plants or animals are alive, and just as we could say that the sun, with its spots which shift, swell and deflate, ooze into each other, merge and are one more displaced – and when they swell or shrink, do it rhythmically and internally – so one might say that the sun is alive. It is as if this anarchy still haunts our lands.” With that, the French avant-garde thinker has exposed the underlying possibility that ruins, buried many times over, are as capriciously human as anyone walking over them, however unknowingly.