© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

Turkey announced its 10-year National Space Program last week, receiving widespread attention on both national and international media and social media. The subject has a cultural aspect, as well as its economic, political and scientific sides. There has been hype on social media for finding a Turkish version of space-related English words, the primary being the word “astronaut.”

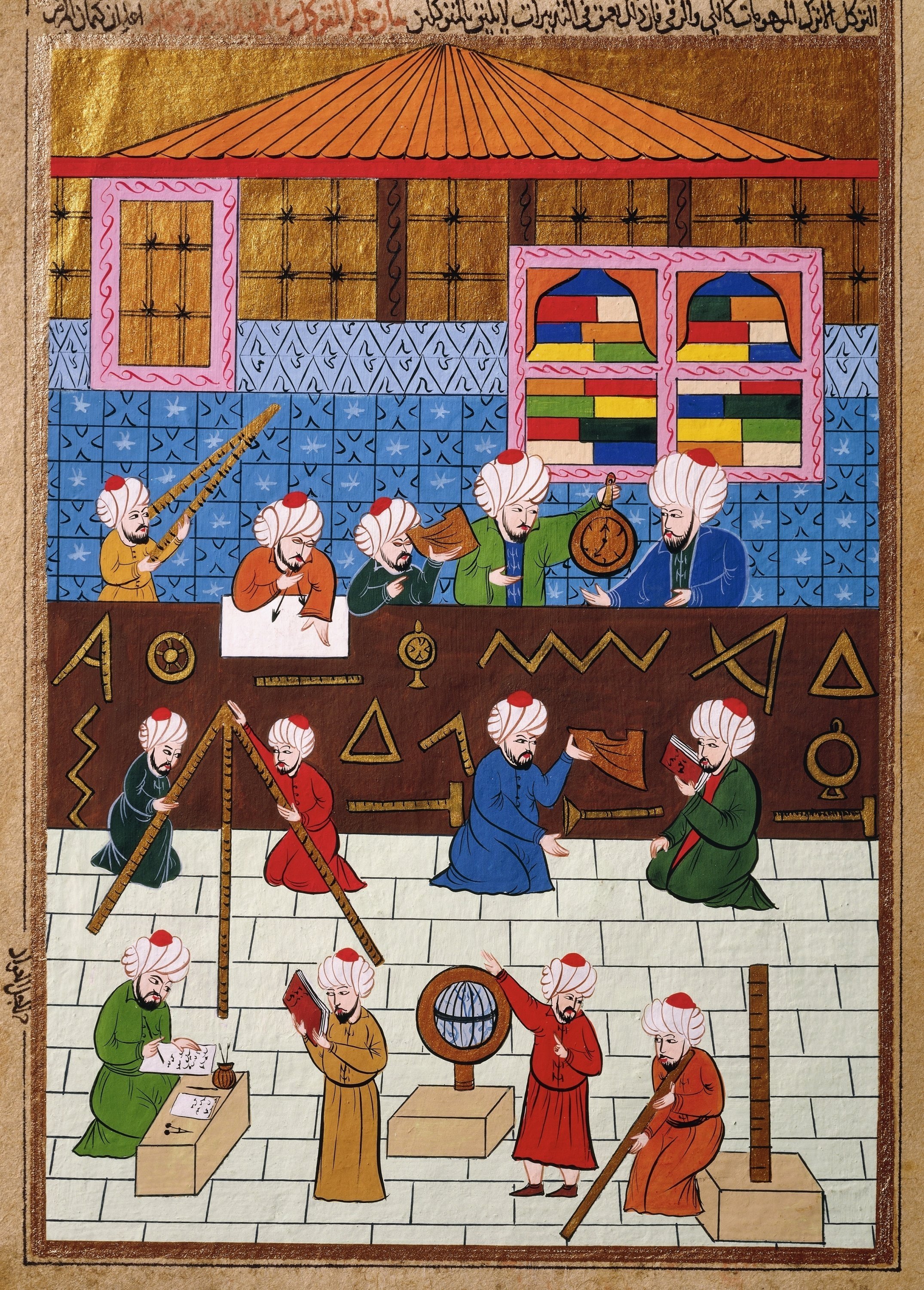

The scientific world and culture-art world unite at some points. So, it is very likely that we will see productions dealing with space studies in painting, theater and cinema in the upcoming period. It is surely necessary that the history of science should be examined to give space studies a national aspect. Let us look at the sky and space studies that stand out in Turkish history.

Turkish history is actually familiar with space and astronomy studies. From the Göktürks to the Ottomans, Turks have a deep-rooted history of astronomy both scientifically and culturally.

As part of the post-Republican language revolution, Turks invented the word “gökbilim” to refer to “astronomy,” comprising of the Greek words "astron," meaning heavenly body, and "nomos," meaning laws. However, this concept did not work, and astronomy became widely used in Turkish. The Ottomans used the terms “ilm-i nücum,” “ilm-i hey’et” and “ilm-i felek” for it throughout Islamic history.

Going back to earlier periods, we see Turks have always dealt with the sky and the stars. As they were nomadic, they sorely needed to know the state of the days and seasons. Therefore, knowing astronomy was an obligation to regulate life for them. In old Turkish, there were many names of planets and horoscopes called “Ülker,” “Oŋay,” “Tilek,” “Temir Kazık,” “Yediger” and “Ülgü.”

The most obvious example of their interest in celestial bodies is highlighted in the “Epic of Oghuz Khan.” It narrates that Oghuz Khan, the legendary khan of the Turkic peoples, marries a girl who comes out of a light that descends from the sky to the earth. He names his children from this marriage Sun, Moon and Star.

A special value has been attributed to the sun and the moon, both of which are featured on the flags of many states. They are often used as a metaphor in both written and oral literature and in decorative arts.

A sacred value has been attributed to the sky as well. The ancient Turks believed in one God since they entered the historical scene. They called this God “Köktengri / Göktanrı,” literally meaning the owner of the skies. In fact, the sky here has a metaphysical meaning. According to this, there is only one God that is not limited to space and time outside the visible and invisible heavens, that is, the universe.

The interest in the sky, or rather in space, was not unique to the Turks. For many civilizations in ancient times, space was a special subject of curiosity. In the Middle Ages and before, the knowledge of astronomy and astrology was mixed. Those preoccupied with astronomy were considered soothsayers.

Islamic scholars played a big part in the separation of these two branches. After all, with the spread of Islam, astronomical studies in the Umayyad (661-750) and Abbasid periods (750-1258) made great progress. These endeavors were encouraged by a divine appeal, beyond simple curiosity or need that any civilization had.

Many parts of the Quran touch on celestial bodies, saying that everything in space is a sign of the power and might of Allah, just like living and non-living beings in nature. They also imply that the dimensions of these bodies and the harmony between them should be looked at and studied carefully and a lesson should be learned from them.

This divine encouragement also broadened the horizon of Turks who were already curious about the sky. Many Muslim scholars began to study astronomy. The books prepared by science historian professor Fuat Sezgin in Germany, which also received science awards, reveal all these developments.

The first serious studies in this field in Turkish history are observatories established during the time of the Great Seljuk Empire (1037–1194). The Shia Fatimids undertook intense scientific propaganda in addition to their political and military moves to destroy the Sunni Seljuks. During this period, the famous vizier, Nizam al-Mulk, started opening madrasas all over the Seljuk Empire to strengthen Sunni Islam and train the scholars needed by the state.

These structures established in Baghdad became an exemplary model for the entire Islamic world over time. One of the most famous scholars who taught for many years in these madrasas, which also pioneered astronomical studies, is the Islamic jurist Al-Ghazali. In one of his books, he says: “Anyone who does not know the sciences of anatomy and astronomy cannot understand the existence and might of Allah well.”

In this environment, astronomy was seen as a science that had to be learned to a certain level, and astrology was seen as a discipline based on interpretation. It was considered important to teach astronomy in madrasas to a certain level. Orientalists refer to all these scientific works in both the Sultanate of Rum (1077–1308) and the Great Seljuk periods as the “Renaissance of Islamic history.”

There are dark ages as well as golden ages for civilizations throughout history. Unfortunately, the Mongol invasions that reached as far as Baghdad destroyed all this scientific knowledge in the Seljuk Empire and plunged them into darkness. The works that scholars had written for years were ruined, with very few of them being saved. Historians say that the rivers Euphrates and Tigris first were red from blood and then ran black with ink.

The Ottomans took over this ruined heritage and tried to develop it. They needed to make measurements of the sun the moon, stars and planets and wrote books on them. Fortunately, the educational approach established and continued by scholar Shams al-Din al-Fanari followed in the footsteps of Al-Ghazali’s way of thinking and embraced exact sciences as well.

Although the transfer of scientific studies was interrupted, the astronomical works of those periods continued to impact the culture. As of the first century of the state, this impact prevailed, having reflections in various branches of art, from architecture to literature. For instance, a large mosque was built in Bursa, one of the first cities conquered by the empire, by Sultan Bayezid I, nicknamed “Yıldırım” (meaning Thunderbolt) between 1396-1400. The Great Mosque’s minbar, the pulpit where the Friday sermon is preached, features a kind of three-dimensional solar system embossed with highly aesthetic embroideries. The planets, including earth, are round in this relief. Astronomical elements like this are used as ornaments in many artifacts.

Ulugh Beg, a Timurid sultan and a famous astronomer and poet from Uzbekistan, is a special figure for Turkish history. Ali Qushji, one of his pupils, also had a special place in the history of Ottoman science. Thanks to the efforts of Sultan Mehmed II, also known as Mehmed the Conqueror, Qushji was brought to Istanbul. Positive sciences were further revived when he started to give lectures in madrasas. Thus, the educational institutions established during the reign of Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror made a great breakthrough in this field. These efforts came to fruition in the 16th century.

Behind the power of the Ottoman Empire in the seas is this knowledge of astronomy and geography. In the Ottoman classical period, navigators improved astronomical studies further. Turkish navigators such as Piri Reis and Seydi Ali Reis contributed to this field both theoretically and practically with their works.

After the 17th century, the wars that the Ottomans fought due to the empire's geopolitical position, as well as internal revolts and its low population in proportion to its territory accompanied economic problems. So, it experienced a technical setback. But despite these, they closely followed modern astronomical studies in the West and translated them.

For example, Andreas Cellarius’ “Atlas Coelestis,” which was published for the first time in 1708, was translated into Turkish by Ibrahim Muteferrika by command of Sultan Ahmet III. Thus, an independent work dealing with old and new astronomy entered Ottoman literature.

By the 19th century, the efforts of Sultan Mahmud II to modernize educational programs proved quite successful. New astronomy concepts and information in great detail entered the literature through the contributions of Ottoman mathematician and engineer Hoca Ishak Efendi. But the lack of economic opportunities to go beyond this and political crises foiled many enterprises.

Time and possibilities will also show how far the space program announced for the next decade will go. All of this is directly related to the economy. Experts note that Turkey has set a horizon. In other words, the main goal is to pave the way for activities that ensure the development of the country in all areas, especially technology.