© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2025

When an artist experiments with the notion of autonomy, they begin to approach a social dimension in which their personal expression becomes transpersonal, leaping beyond the confines of their specific individuality into the collective sphere of interpretation, consensus and history. What began as a way to keep records, to quantify possession, quickly evolved into the contiguities of linguistic symbolism.

Even in the most humdrum of daily conversation, the abstract intonations of emotive speech contrast with the complexities of logic as two competing representative forms by which to convey, affirm and share mutual definitions of reality. They are both complementary and conflicting subconscious motivations that aim to preserve certain norms of social behavior. But the artist, by profession, oversteps these boundaries, as a silent witness and enfant terrible.

Under the influence of her own peculiar order of creative chaos, of methodical madness and imaginary engineering, Inci Eviner is a keen draftswoman with a mind for the image as a vessel of meaning. Hers is an unprecedented ideographic vocabulary, otherworldly yet uncannily urbane. She is playing a cosmopolitan sport in which disciplined practitioners of the fine arts taunt masked dilettantes weary of esoteric sensibilities and impractical inventions.

“What Remains, What Returns and Implications” is not without a sense of humor, however opaque in its dark, oblique evasions and flirtations with familiarity. The works of Eviner demonstrate a liberated hand, one that, since her birth in 1956, has resisted the cold weights of industrial pressure and economic obligation.

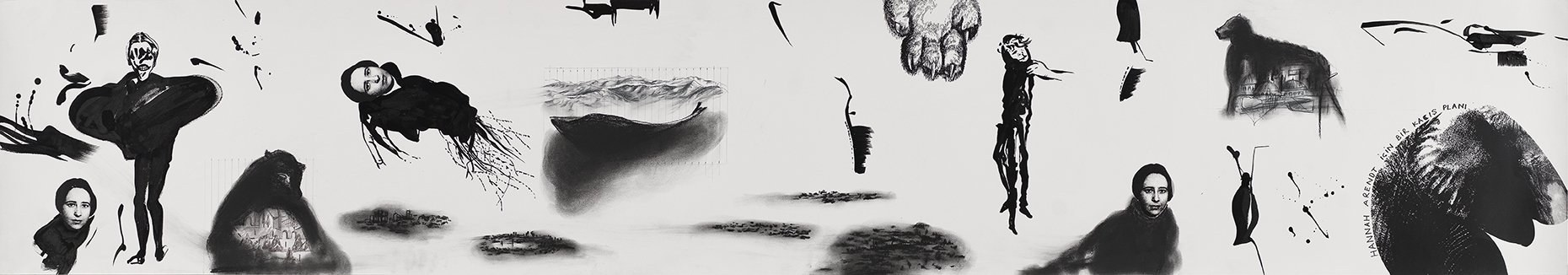

Her visual quotation of German-American philosopher and political theorist Hannah Arendt’s face invokes social commentary on the nature of observation and its dissolution before the irrationality of absolutism. The piece, of ink, charcoal pencil and silkscreen on paper, titled, “An Escape Plan for Hannah Arendt” (2020), replicates the philosopher’s enlightened, youthful visage as a motif smudged against encroaching wild animals and bleak landscapes.

A picture imperfect

Of the 10 artworks on display at Galeri Nev Istanbul for “What Remains, What Returns and Implications," Eviner made all of them in 2020 and they are all framed to a width of 230 centimeters and between 40 centimeters to 50 centimeters high. The broad, narrow scope within which her drawings are angled provoke a particular perceptive mode, one that by its spatial consistency and it being parallel to the longitudinal plane, implies virtual distance.

Suspended at average eye-level, Eviner’s multimedia drawings are textual, as mostly Turkish, also English, phrases climb upward and along the abstract and figurative impressions and their often dissonant mergence with the blank, white background. Mostly dichromatic, according to the greyscale of ink and charcoal as its blacks are absorbed and fade sideways across the silkscreen-on-paper medium, Eviner relays a muted, yet no less diverse plurality.

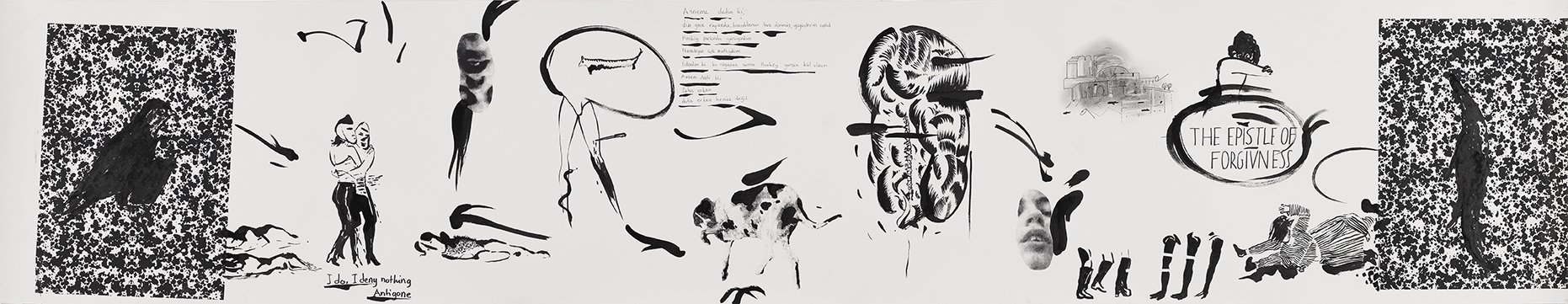

In one piece, “The Epistle of Forgiveness," Eviner explores her signature erudite intrigues by quoting from the classical play of “Antigone,” “I do. I deny nothing." The author, Sophocles, wrote the lines in the fifth century B.C., as the lead protagonist’s response to Creon, the ruler of Thebes. It is arguably a pivotal dramatic moment in the play when Antigone confesses to burying her brother, Polynices, who perished on the wrong side of civil war.

Eviner spelled out the dialogue of Sophocles, in handwritten English, under a pair of full-body human sketches. The couple embraces tightly, surrounded by a confounding maelstrom of stray lines, an upturned printed face and semi-representational landscapes that appear to be either a person reclining, a slope of distant hills, or both. And beside them, a rectangular field of splotches about a smear adds subjective, dimensional depth.

“The Epistle of Forgiveness” is, like every work by Eviner at “What Remains, What Returns and Implications," an agglomeration of unfinished details, flashy effects and partly, though upturned or sideways references to prehistory juxtaposed against more familiar historical themes. In one example, a fashion drawing of a slim-legged feminine stance is overrun from the waist up with a thought-bubble inhabited by a strange, mammalian creature.

Impossibilities of description

It is obvious that the works of Eviner for “What Remains, What Returns and Implications” are not easily conveyed in words, even if they also are within the works themselves. But it is because of her encompassing vision, one that stretches consciousness of perception to the edges of the knowable, which makes her art so difficult to capture and relay through any other medium. To attempt to do so is wildly presumptuous.

It could be argued that the relationship between words and images diverges in the literality of symbolic sounds. When a sequence of phrases is rearranged, its meanings change in the same way that alternating perspectives might reveal entirely new visual experiences of the same artwork. Limiting her colors to gray scale and occasional flits of red or flashes of gold, Eviner wisely minimized the degree of variation to the cold, hard multiplicity of forms alone.

By placing geometric decoration alongside action splatter, such as in her piece “Elephant” (2020) Eviner triggers an order of cognitive dissonance that is at once unsettling, and bewildering, while also retaining a certain aesthetic appeal. There is a sense of movement in her works that approximates sonic, bodily tension, a kind of compositional or choreographic arrangement of the tableau, conceivably intended for experimental performers to interpret.

The experiential potency of Eviner's drawings is that they decentralize the act of seeing from that of the seer. They are counterintuitive, filled with spontaneity and the magic that turns life into stories, memories and art. Eviner has sought to draw a meandering line to distinguish, however indirectly, the difference between clarity and visibility. Because something can be seen does not mean it can be understood.

Eviner uses a tantalizing phrase, “images unconsidered," to project her intentions behind making her artwork. Those footsore wanderers and hardy art lovers curious and fortunate enough to spend a few quiet moments with “What Remains, What Returns and Implications” inside the silent, ethereal white cube interior of Galeri Nev Istanbul will come out with their doors of perception slightly more cleansed, so to speak, to quote Aldous Huxley.

“What Remains, What Returns and Implications” is bracing in its originality of focus on that which is seeable across the contemporary horizon of worldly affairs, like the ongoing perils of commercial whaling. Reminiscent of the surrealist painting by Hieronymous Bosch, Eviner explores elements of fantasy, as in the piece, “Kuleli Military High School Tunnels and the Monster of Çengelköy (2020).