© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

“I must write the way she talks, I said to myself, by leaving chasms, by leaving the bridges I’m building half-finished, by forcing the reader to fix their eyes on the current underneath,” Lenu, the narrator of the Neapolitan novels says, talking about her childhood friend, confidante and nemesis Lina, or Lila, according to Lenu’s whim. This declaration comes in the fourth and last novel in the series and serves as the best description of what Elena Ferrante does with the book. She leaves gaps, starts explaining certain events, leaves us ill-informed and picks up the pieces maybe 100 pages later, or maybe in the next installment. This is, you can say, the way she weaves her narrative web around us, and the more we read, the more entangled and implicated we feel.

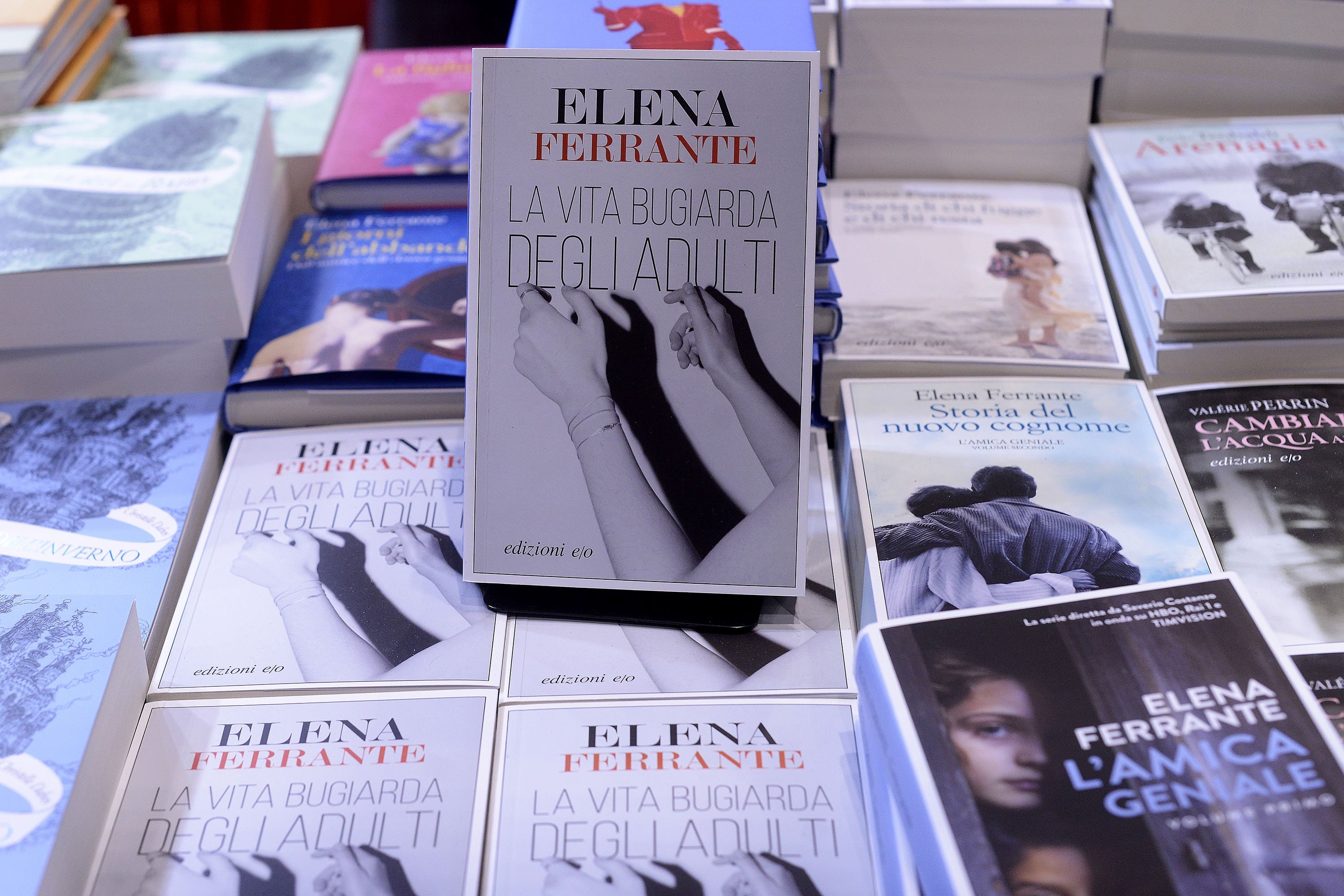

Everyone is on their own timeline when it comes to Ferrante. Many were introduced to her Neapolitan novels as they were still being written in the last decade and were overjoyed to get their hands on “The Lying Life of Adults” in 2020, in a year when there was not much else to look forward to. I have friends who got to know the Neapolitan novels at the start of 2021 and devoured them in a matter of weeks. I myself started with the excellent TV series back in 2018 to see what all the fuss was about. With the start of the pandemic, I picked up the second book, read the third pretty quickly after and, possibly not wanting a good thing to come to an end, delayed the reading of the fourth. Now that that’s also under my belt, I can look forward to the last Ferrante and then go back and read her first.

Time moves differently in Ferrante’s world. The Neapolitan novels start with Lenu being mad at Lila in her old age and then taking us back to their childhood. It is a story that keeps looking backward and so encourages the reader to look back on their own life too, and this sweet encouragement to wallow in nostalgia must be one of the attractions of the book. I try to remember when I first heard of Ferrante. I recall vague memories of her book-covers in shops in the U.K. And then a British friend singing me its praises as I showed her around Balat, which will later, in my mind, become the Turkish stage where the action takes place.

Not feeling ready to plunge into a saga, I was finally tempted by the TV series. From the very first moments of the credits, I was hooked. To see my own face and the faces of Turkish cinema actors from the golden years stare back at me from the screen, here is something genuine, I thought. People had recognizable faces, though I am not quite certain from where. Old family albums or Yeşilçam films? It hardly matters because I know whatever is on the screen is about me, the stories are being told about my city.

Many have argued that the attraction of the Neapolitan novels lies in capturing a certain kind of female friendship that grows from having suffered from the same kind of privations. We are in a slum in Napoli, and may as well be in Balat, when we consider the family and neighborhood ties, the little despotisms of the slightly better off, the prestige of owning a shop that sells food, which means that the owners will always have something to eat. In this environment, the much-mythologized friendship between Lenu and Lila is forged through a ritual that is as violent, if not even more so, than a blood-brotherhood. Lila throws her doll into the basement of a building where the local mafioso lives and invites or challenges (there is no way of telling when we’re talking about Lila) Lenu to do the same.

I used to play with friends who lived in such apartments and I remember the absolute horror those unused spaces held for me. We did sometimes go down, but never alone, and I am glad no friend of mine ever made me throw down a doll there. It also brings back memories of "the one feared neighbor." In my case, he was not connected in any way to the mafia, but we, the children had the unshakeable belief the man was capable of anything (he had not laid a hand on any of us, but we had always heard rumors that he had). The Neapolitan novels jolt these back into memory, and it feels like an ersatz way of recalling the past, filling in the blanks, showing you the mechanics of how your childhood world worked. Now you know.

After this fearful childhood, the second novel is about Lila and Lenu’s teenage years, when Lila fulfills her promise of manipulating Lenu. She keeps insinuating to Lenu that she knows more about life and the neighborhood, which leads Lenu to do reckless things just to keep up with her. But she can never catch up with Lila’s worldliness, as Lila gets married very early, has her own house and becomes a woman in her own right.

What really remains of the second novel in memory is the endless days on the beach, of swimming, of drinking sweet soda, eating ice cream and of wondering if your (married) best friend is flirting with the boy you have set your sights on. When Lila does betray Lenu you are not surprised – because a girl who made you throw your doll down that hell hole is capable of anything. The problem of Nino, the boy in question, stays central through much of the second and third novels, and only towards the end of the fourth does his spell wane and you sigh a sigh of relief as you reach your fifties with Lenu.

In the third novel we get a better sense of Lenu as a writer, and so look back on what we have been told with a more discerning eye, guessing and hoping that she may have done some of the manipulating herself. This retrospectively empowers Lenu and this installment finishes with her vindication; of Nino finally preferring her over Lila. After this, in the fourth novel, Lenu and Nino have their moment in the half-sun, as by this point they are both married with children. Because this is Ferrante, and because they have somehow both managed to go back and settle in Napoli after their wanderings, the rule of the "mahalle," or "neighborhood" prevails, and they start to fall into the patterns of violence and deceit they have inherited from their parents.

This is one of the central precepts of the whole series, that you can take the girl (or boy) out of Napoli, but you can’t take Napoli out of the girl. Towards the end of the fourth book, we learn that Lila is researching the history of Napoli, and so after all the lived experiences we also get a tourist guide treatment of the place. There is no doubt that Napoli is its own thing, with its own language, no doubt influenced by the cultures of the other side of the Mediterranean.

The Neapolitan dialect seems itself to be a character in the novel, and it acts as a barometer of emotions for all characters. Having spoken standard Italian through her university and literary life, Lenu “lapses” into the dialect when she gets emotional. When circumstances lead her to settle there again, she is alarmed by the ease with which her daughters, raised in much more “cultured” circles, slip back into it, not least because they see their idol, Lila, speak in that dialect. Having somewhat weaned herself from her Lila addiction, Lenu now sees that her daughters are attracted to her and her son.

It is also sobering to see the original object of (sexual) attraction Nino lose his power, as he proves himself to be the irresponsible ladies man he always was. This is acceptable for Lenu to a certain degree, but when it’s coupled with his indifference towards his children he becomes unbearable and in fact the villain of the piece. It is painful also for the reader to let go of the dream of the passionate man of ideas as the ideal partner. Lila, of course, like all other experiences, gets to that point of disillusionment with Nino before Lenu and, indeed, the reader.

Throughout the series, Ferrante delivers on Lenu’s project of building this improbable structure, like an Escher painting, with staircases and bridges ending where they started. Ferrante’s flashbacks and flashforwards, which she introduces sometimes without warning, mark her style and help jolt our memory and connect bits of the story together. More than anything, it shows us how difficult it is to make sense of one’s own life story, and urges us on to read, to root for Lenu to make sense of her own in our stead. And when we have willed her and ourselves to the end of the fourth novel, neither she nor we are surprised that we are back at the beginning.