© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

In his posthumous, “Letters to a Young Poet,” the fin de siecle German-language Bohemian poet Rainer Maria Rilke had no patience for criticism, and less for journalism. In the last of his ten letters to a 19-year-old officer cadet in the Austrian military, he lauded the boy for not stooping to the “unreal half-artistic professions” which “pretend to be close to art” and “in practice deny and attack the existence of all art”. In his poetry, Rilke thought of himself as bound to the visual arts, more than music.

Such is the case with his two-part collection, “New Poems,” which Dirimart’s curator, Ceren Erdem quoted for the title of the current, group show, “All Else Is Far”. The phrase appears in the third part of the poem, “Island,” which, in the elliptical lucidity of Rilke embodies the human will to press forth, unknowingly, on earth as in the stars. It is a feeling that conjures the intensity of loneliness, at the edge of life, when existence comes to a point, a decision of just how to get on.

That poetic desperation is at the core of “All Else Is Far,” its metaphysical sentimentality beautifying with a visceral lurch through the noosphere. The curation is an utterly sensitive one, nothing of the slapdash agglomeration of objects that characterizes many group shows, which can seem utterly arbitrary, a critique that, in fact, came to haunt Rilke himself after publishing “New Poems” in 1907. But that arbitrariness Rilke was defending as a form of selfhood, as each poem was a thing unto itself, an artwork, likened to an Auguste Rodin sculpture or Paul Cezanne canvas.

Erdem has swung back around, perhaps, to configure the placement of apparently unrelated works of visual art into a literal course of shared meanings in which the reason d’etre behind each work both alone and in relation to all of the others is accentuated and renewed from every point of their respective placements and interior monologues. It could be argued, however, that the relatively esoteric significance of each piece is an apt metaphor for solitude, in objectified isolation and yet obliquely together, despite their immediate aesthetic values.

Dirimart has a wall, facing the doorway, often used to preface exhibitions with works that provide a glimpse, a light touch, something evocative yet somehow hidden, so as to whisper a hint of what is to come. Such is the effect of the untitled oil painting by Furkan Akhan against the surface, painted a vibrant orange, identical to that of the elegant, plushly upholstered chair turned around. It is not difficult to imagine the likes of the Godfather, or Morpheus, on the other side, clicking worry beads, awaiting their next guest.

And to add to the domestic flair, Erdem placed works by Sarkis Zabunyan and Yasemin Özcan beside that of Akhan. “Desire” (2020) by Özcan is a piece of sculptural theater, evoking the subtitling of thoughts that would occur as two beloveds are seated for their morning breakfast and while in the midst of passing the butter, are, in fact, navigating inundations of emotive thought, trained on the other, reflecting their inmost mysteries. The simple ceramics lain on a balcony table are engraved with sayings like, “the weather is hot,” irresistibly familiar.

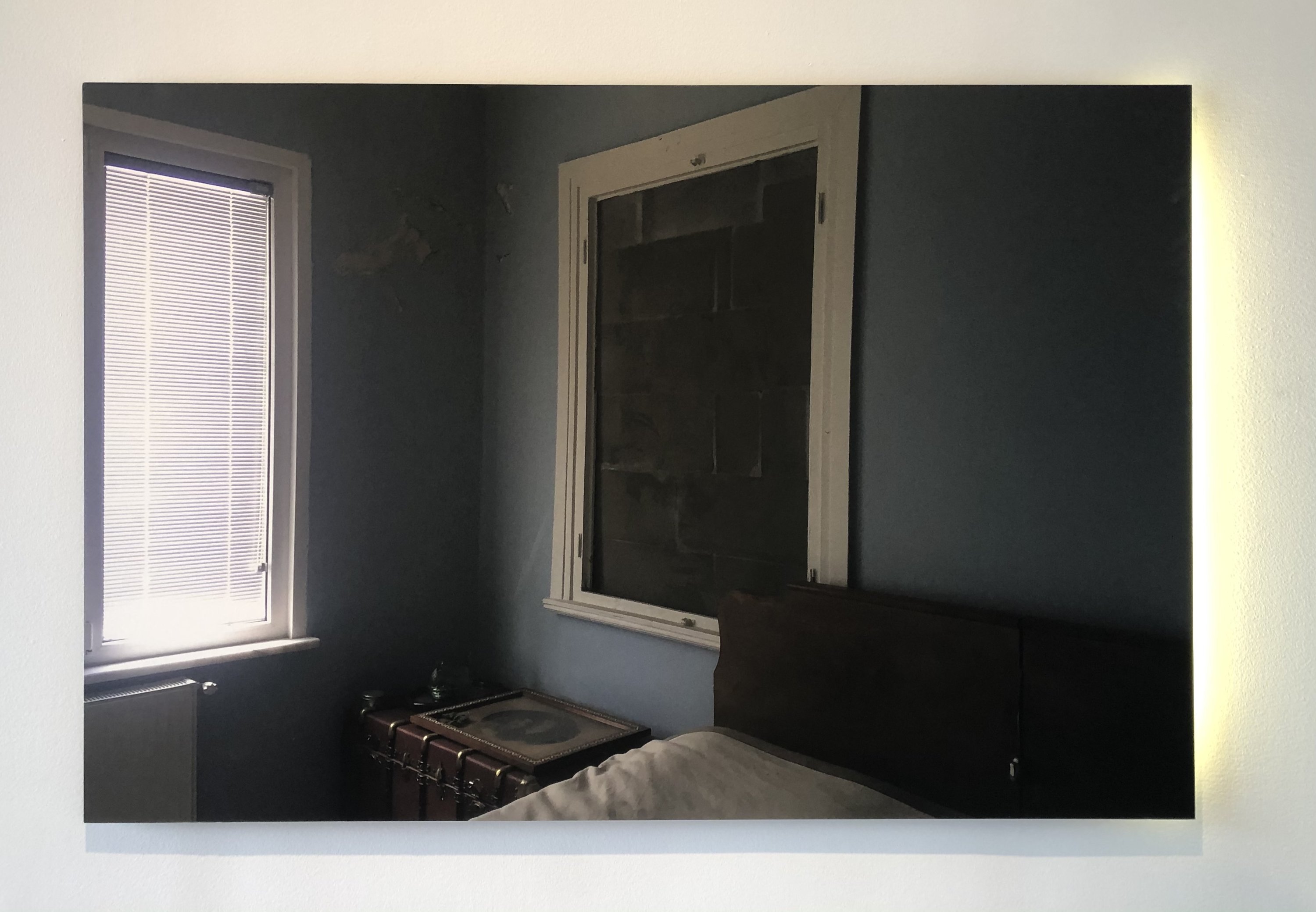

And Sarkis, with his photograph that emanates on one side with LED light, turning the two-dimensional into an image-sculpture with his characteristic visual vocabulary, explores an interiority abstruse to his upbringing. The room is enclosed, one window blocked with bricks, uncanny to so many of Istanbul’s born-and-bred city dwellers, like Sarkis himself, raised stretching for light like plants with stems bent toward the window. There is a solid weightiness to his capture, unpeopled, like a vacant memory, semi-imagined and lingering.

Wrapping around the introductory hall, “All Else Is Far” opens out to an invitation of bodies exposed, both explicitly and by visual inference. Yet, these exhibitions are not garish but instead imbue their seers with the definition and essence of their making, and presence, effervescent with the ingenuity of their creators, the artists whose disparate and interdependent universes meet at points, like a full-blown kiss, or an unwelcome graze. Others are gestures that elude physicality, like the wood sculpture by Can Küçük, “Both” (2015).

“Both” comprises two stools. One of them is cut, diagonally, at the leg, and that piece is then upturned and set in the middle of the seat of the other, rendering them, both useless. As a whole work of art, they need each other. In that process, practicality is lost. It is that superfluity that makes humanity human. On the reverse side of the opening wall, a surreal figment of the nonfigurative drapes, curiously, exuding its artist’s rudderless, improvisatory approach to painting with mixed media on found surfaces, in the case of “Untitled” (2021), craft paper.

Perhaps one of the more didactic works at “All Else Is Far” is by Ayça Telegren, whose 40-second video loop, “First Encounter After Break Up” shows two pairs of hands clawing at the sand where the sea water washes ashore. The overarching push and pull of the tide has its resonance in the back and forth of the waves that break over the earth, and out of that rhythm, yogic and fundamental to material existence, a couple reaches for each other, their grasp weakening as they pull back, and exit the frame.

In certain places, the works of “All Else Is Far” mirror the relationships of their artists, as, for example, Güçlü Öztekin and Güneş Terkol, partners in work and life, as the wall painting of the former faces the embroidered fabric of the latter, hanging from the ceiling. The filmmaker and photographer Nuri Bilge Ceylan has a work, “Sleepless Night” (2008), in which he pictured an intimate moment of his late father, at the end of his life, eyes wide in bed, elderly, and facing death’s approach. Ceylan filmed his father throughout his career, building a special relation to the image of his maker.

To add historical depth to the show, assistant curator Levent Özmen tipped Erdem on an oil painting from 1986, by a lesser-known Turkish artist named Celal Tutant. His canvas, titled, “On the Sofa”, is of a contorted human figure, asleep on a couch for one. The nighttime emotionality of its scene is universal, instantly recognizable, especially to anyone who lives on their own, common among artists whose lives are often defined by how they grapple with the demons of loneliness when the momentums of society feel exactly opposed to the originality in their hearts, and which they realize, regardless, through courageous acts of work, perseverance and survival.