© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

There is a similitude between sound and sculpture, particularly in terms of their appreciation, when exhibited as contemporary art. The projection of sound is not visually demanding, and so by its mere presence, it provokes a confrontation between what is sensed and not sensed, and what is interpreted, both by an individual previously unaware of its existence and by the artist and his curatorial team who were thinking of the creative process and presentational contexts of the piece for a substantial period of time prior to its public exhibition.

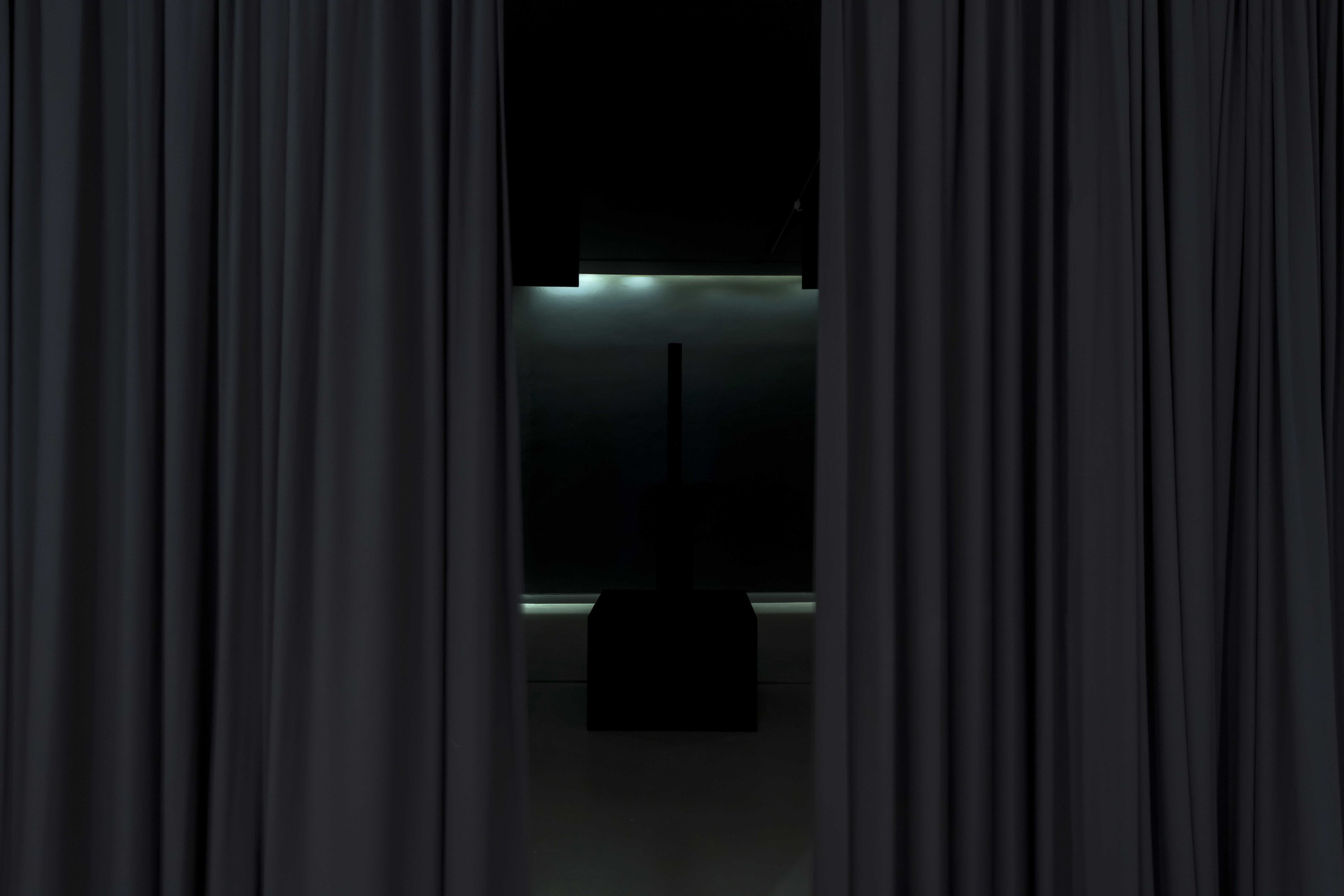

With a mere superficial gaze, simply by lending an ear, the latest artwork on display by the sound installation artist and academician Selçuk Artut is an opaque horror show with the ambiance of stir-crazy creativity, confined to the reflexive interpretations of its own incomprehensible, inner world. At first impressions, it does not bear the erudite sophistication of its author. There is a mass of explanatory text on the wall before the main hall’s installation. A reflective, digital enumeration counts down the seconds, and then it begins.

One hears the machine whirr of the piece, a configuration of nine poles that, like stalactites and stalagmites in a cave, emerge from the floor and ceiling. The slow, automated movements of the protruding metal cylinders, extending from rectangular black bases, as box-like foundations, further invite the mind into a sculptural setting. Yet Artut is an artist of sound, and so that is the focus of his creation. In short, the piece is a garbled spread of spatial dissonance. The evocation is that of raspy voices, struggling to enunciate a vowel, yet their mouths are full of dry air.

As a pedagogue of voice and interaction at Sabancı University, where he runs the Visual Arts and Visual Communication Design program, Artut is steeped in the nature of sonic phenomena. With his installation, “If These Walls Could Hush,” he has innovated an environment in which the primacy of sound engages in a peculiar course of dialogue with its mechanical source. It is comparable to a voice, that, purely itself, attempts to break through the complexity of the body and project its self-expression, yet is utterly obstructed by inhuman acoustical rendering.

As a sound performer

Artut is active in the studio and on stage with at least two projects. Since 1998, he has been a part of the post-rock avant-garde band Replikas. One of their most popular compositions, titled “Yaş Elli” (loosely translated as “Age Fifty”), revolves at a deliberate pace around a rhythm weighed by an elastic drum kit playing to the traditional Turkish zurna, a rustic woodwind. And more recently, with collaborator Alp Tuğan, Artut has led wavelengths as part of the performance group RAW, whose shows integrate audio and visual elements via live coding.

An aesthetic line can be drawn between the sculptural audio installation of Artut and that of Cevdet Erek, particularly the reincarnation of his piece, “Bergama Stereo,” at Arter. Both artists demand a full-scale research agenda in order to adequately apprehend the sense of direction they engender through their sound works. Erek referenced Berlin nightclub music and Turkish davul drumming. Artut’s choice for the sculptural shape from which his sounds issue is reminiscent of the historic, renovated domestic architecture of Istanbul that inspired Erek.

Yet, these observations hover around and pass through the emanation of sound that centers Artut’s installation. It is, in that sense, a reflection of the experience of his work, as a body moves in relation, immersed in an acoustic setting. If the immediacy and penetrability of Artut’s curated projection is an indication of its experience, it is possible to speak of its personal effects. For example, the compromised quality of the sound, its vague harshness, commingles with the darkness of the gallery hall, triggering repulsion, even disgust.

“If These Walls Could Hush” has a serpentine, slithering, whispery character. If it were made of light, it might strobe, flicker and dim with an erratic multivalence. The overlapping of inarticulate voices spans temperaments that are at once low while touching the surface of human utterance, transforming into something hybrid, not exactly anthropocentric but both animal and machine. Artut intended to convey silence, an abstraction that, like right angles, does not exist in nature, but as a fantasy, born of the mysterious human capacity to grasp at absolutes.

A soundless vibration

In his conceptual text published by Zilberman Gallery to accompany the otherwise materially austere exhibition, Artut muses on the interrelationships between sound and the contrasts of its emergence in interior and exterior space. He makes reference to certain metaphors to describe sound and its absence in terms of psychological states, such as an invisible curtain. Unlike painting, or even sculpture and visual arts in general, sound art does not fall into the same theoretical categories of objective and subjective definition.

Artut wrote with symbolic potency: “Our lives are surrounded by walls. Even though we try to bury and hide all our secret experiences under a tree they sprout and come out into the sun. Yet walls do not want to hide anything. They have peculiar colors, smells, textures, as well as sounds, although we think they will never hear them. It might be that they are not struggling to be heard but actually, walls do have a language. And the good thing is, they never lie. They do not try to hide from anyone what is happening, all the treachery and the wrath.”

Zilberman Gallery redesigned the interior of its main curatorial space for Artut’s installation and it would seem that the artist has used sound to draw the attention of listeners not to the resonance itself, but to the way that the sound is related to its medium, that being the bulky valves employed to give sculptural shape to his piece. Moreover, his is a nonverbal, aural comment on gallery acoustics and their influence on thought and perception. “If These Walls Could Hush” can be heard as an exaggerated gesture of reflexive and institutional criticism.

It is not an easy search to discover the origins of the phrase “if these walls could talk,” presumably the derivation of Artut’s fifth solo exhibition title at Zilberman. The idea of their hushing, however, has the connotation of the walls not merely having a voice and using it, but that of asking whoever or whatever might be between them to quiet down, even to be silent. By definition, walls have an effect on sound. They reflect and absorb vibrations recognized by auditory vestibular nerves in the brain. They are the silence that creates sound.