© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

Although one of the key figures of good in the Middle Earth of J.R.R. Tolkien’s "The Lord of the Rings" is the magician Gandalf and its key architect of evil, Sauron is also known as “the Necromancer,” the use of magic in it and its related stories is kept pretty subdued. When Sauron is an active character before becoming merely a tower-bound symbol of evil, he tends to get his way through the power of persuasion. As for Gandalf, the reason he is restrained in the use of magic or even often absent altogether is that Tolkien wants to test and develop his other characters in the most trying of circumstances, which could not occur if he and his magic were always on hand, or on staff, to rectify the situation.

Yet magic is used to create an impressive display at the beginning of "The Lord of the Rings" with Gandalf’s otherworldly fireworks. These are superbly rendered in Peter Jackson’s three-part film adaptation of "The Lord of the Rings." It is symbolic that it does so for the film series, which has a magic of its own, carried over from the books. It is that it can tell a story based on long-discredited chivalric mores and replete with clichés to a cynical age while keeping its viewers on the edge of their seats for much of the roughly ten-hour-long spectacle.

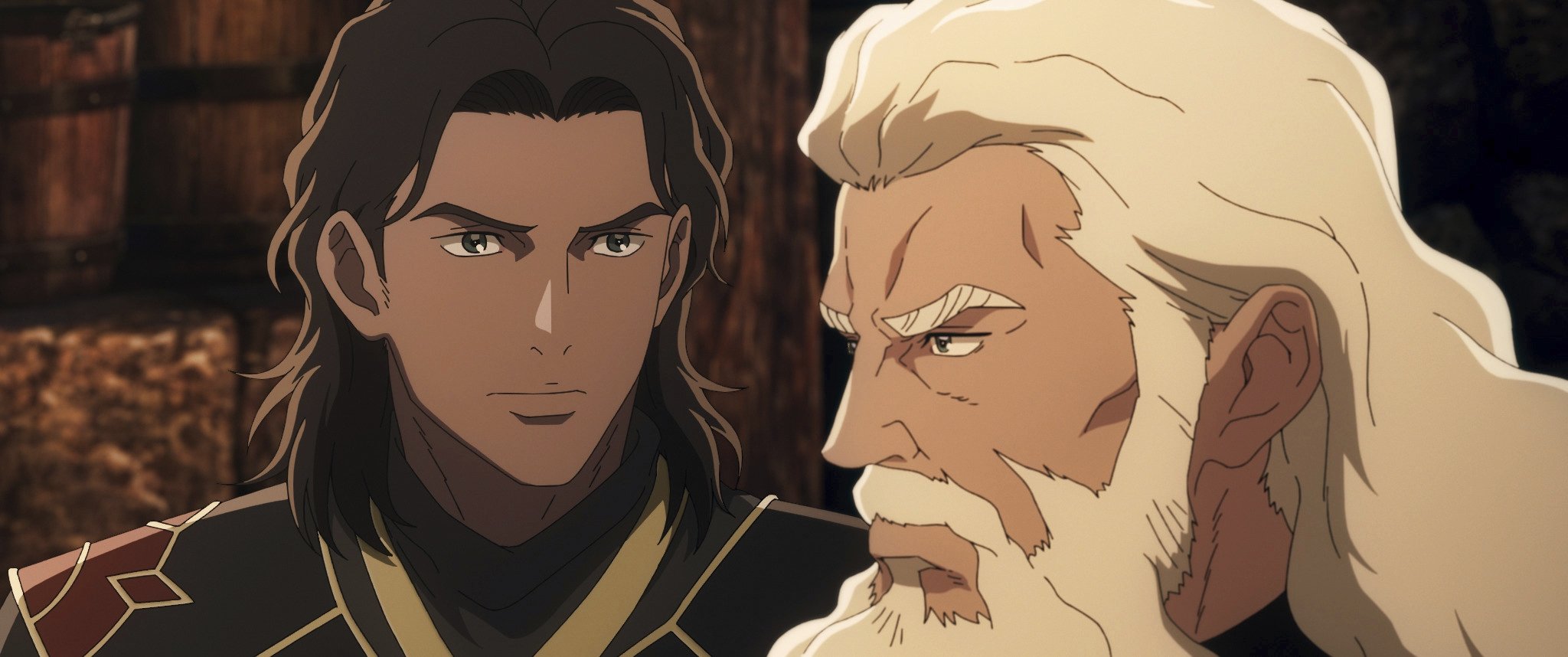

This elusive magic ingredient, however, is sadly missing from the latest screen adaptation of Tolkien’s universe, the just-released Anime-style animation "The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim," directed by Kenji Katayama. This is not because the film has attempted to distance itself from Jackson’s movies. On the contrary, it overtly links itself to the more extensive series, not only in its opening statement that “All Middle Earth knows the Tale of the War of the Ring” but in that its narrator is none other than Eowyn from that series, played there and voiced here by Miranda Otto. The tale she narrates is, however, a new story, one that predates the story of the prequel to "The Lord of the Rings," "The Hobbit," by two centuries.

As befits a tale narrated by Eowyn, the princess of the Rohirrim, the Viking-like horsepeople of "The Lord of the Rings," it is about her country, the Kingdom of Rohan. The storyline for this new film is drawn from four pages (in my copy) of the extensive Appendices to "The Lord of the Rings." The brief account there tells of Freca, a rich, ambitious landowner, who comes as an ambassador to the King of Rohan, Helm Hammerhand, in the latter’s capital of Edoras. In seeking to raise his family's status, Freca has come to ask “the hand of Helm’s daughter for his son Wulf.” Helm, who has neither trust nor respect for Freca, insults him, leading to an exchange of words that ends with Helm striking Freca dead with a single blow.

Helm follows this up by banishing Wulf from his kingdom. Four years later, Wulf returns at the head of a force of Dunlengings, the perennial enemies of the Rohirrim and a people to whom Freca and Wulf seem to at least partly belong, and a war commences in which, initially “the Rohirrim were defeated and their land was overrun.”

The basic story of the new film is drawn from this and imaginatively added to by the filmmakers. One point where the film takes its own direction is with the aforementioned “Helm’s daughter.” Unnamed and uncommented by Tolkien himself, she in the film is given the name of Hera, and this character, voiced by Gala Wise, is made the center point of all the action that takes place. As she is only really tangentially a figure of the Tolkien legendarium, this provided a rich, dramatic opportunity for the filmmakers to make something new and exciting while remaining within the framework of Tolkien’s account. They squandered this opportunity, though, by failing to develop her character, or indeed any of the others.

From the beginning, Hera is presented as a fearless Rohirrim princess. We were informed that she could ride before she could walk. She is described as “wild” and “headstrong” and a favorite of her father. Her martial ability is soon revealed in her somehow being able to lift a spear from the ground while remaining mounted on her horse. In short, she is an independent, self-assured kickass princess who proves simply that she can act independently and kick ass. These may be admirable qualities in real life, but in a story or a film, they render her highly predictable and, therefore, dull.

A further element of dullness is that the film seems to feel compelled to constantly draw upon and echo the use of the Rohirrim in Jackson’s trilogy. This is understandable in its visual depiction of Edoras and the Hornburg (Helm’s Deep) in the same way as Jackson, or the use of the same music score – as with the use of Eowyn, this shows the two films belong to the same universe. Yet, the new film goes further than this in copying plot points and yet, even worse, failing to carry their spirit. Hera, as with Eowyn in the trilogy, is prevented by her father from going to war, but the outcome this time lacks dramatic intensity. In both films there is a pre-battle speech given by the King of Rohan to his warriors. Yet the stirring one given by Théoden in The Lord of the Rings just before they charge into the melee of the Battle of the Pelennor Fields is utterly unlike the flat and insipid one given by Helm, even though he is voiced by Brian Cox. The iconic phrase “Muster the Rohirrim” in the new film equally loses its luster.

The film has also placed itself in the onscreen Tolkien world with its many clichés. Whilst those are noticeable but mainly work or can be overlooked, for instance, in Jackson’s films due to the overall tempo and revelations of character, in this dull new movie, they are just irritating. They include such supposed profundities as the comment to Wulf (Luke Pasqualino) that “you may wear a crown upon your head. But that does not make you a king” or the typical came-to-see-the-truth-too-late of Helm to Hera “I should have listened to you . . . I was blind not to see it.” Furthermore, the supposed wisdom can even be questionable. Olywn (Lorraine Ashbourne), remarking on Freca, claims that fat and prosperous men are the most dangerous. In his play Julius Caesar, William Shakespeare claims the opposite regarding physique. I am unaware of any studies that have correlated the level of ambition with the size of a waistline. Still, the figures of key famous revolutionaries seem to prove Shakespeare right.

It is sad to say that there are hints at some interesting themes in the film, but they are left undeveloped to its detriment. One of these is the statecraft of Helm Hammerhand. That he is peerless as a warrior is not in doubt, and he is able to dispatch his enemies barehanded. But when it comes to ruling, he appears somewhat inept. Firstly, a more astute ruler could surely have resolved the issue of the embassy of Freca without having killed him. What is more, as Helm is angling for a diplomatic marriage of Héra to Gondor, perhaps had he more political skill he might have knit Freca’s potentially troublesome region more closely into his realm through actually backing a marriage of Héra to Wulf. After all, up to the death of his father, Wulf displays no indication that he favored his father’s potentially rebellious agenda, and Helm, knowing the mettle of his daughter, could rely on her to forcefully back his interests.

Following the killing of Freca, Helm also could have attempted to mollify an understandably outraged Wulf rather than add to his injury by banishing him. Or alternately, a Machiavellian might argue that Helm ought to have shown Wulf no mercy, and not left a potential enemy alive who could, and indeed would, later take up arms against Rohan.

Then there is Helm’s refusal to listen to sound strategic advice – another echo with the King of Rohan of Jackson’s films – by rejecting the suggestion of his nephew Frealaf (Laurence Ubong Williams) to leave Edoras and what is far worse, making him leave in disgrace for suggesting so. Then later in the Hornburg, Helm makes an offer to Wulf to “surrender” in exchange for the life of his son. Although on a human level, this is understandable, here he puts his private concerns above his duties as head of state despite the fact that in the prosecution of this war, he is asking the people of Rohan to put the interests of the kingdom first.

All these factors are present in the film, but its tone downplays rather than highlights them. This results in Helm appearing neither particularly heroic nor a stubbornly proud King Lear-like figure of interest. It prevents any real emotional capital from being invested in his fate.

The relationship of Hera and Wulf is also rich in potential, but largely unexploited. The film reveals that they have a close childhood bond. This develops into romantic feelings for Héra in Wulf, though on Hera’s part she seems to regard him platonically. The film thus touches on the idea that Wulf’s war of revenge is merely an outward manifestation of a pent-up desire for the person of Héra and an insatiable need for her to respect him. He certainly reveals he is obsessed with her when she is literally barred from his grasp behind the thick walls of the Hornburg. Yet an earlier scene in which Wulf has Hera trapped in his own tower has the greatest potential to develop this theme but is very weakly used in doing so – Wulf making a simple complaint as to Hera’s pride. Thus, this issue also fails to take hold.

Then more widely, the film could also have looked at the resentment of the Dunlendings, which it does not touch on at all. They are merely the enemy in this film, burning Rohirrim settlements – yet another echo of Jackson’s films. Yet in his guide to the work of Tolkien, Robert Foster notes of the Dunlendings that “they hated the Rohirrim, who had driven them out of the northern valleys of Ered Nimrais and western Rohan, so they frequently attacked that country.” As we are today living in a world in which the consequences of dispossession are fuelling conflict this issue would have been both a timely and a fascinating one to investigate.

There is also the issue of why, as Eowyn points out at the beginning, unlike other “olden tales,” there are no “tales for” Hera in “old songs.” The real reason, of course, is that she was never a developed Tolkien character. Yet, by opening the film with the statement of her historical erasure, the film could have explored a reason of its own for it. It also should be noted that whilst the film centers on a princess who counters the fairytale stereotype in being an independent martial woman rejecting marriage as her destiny, Hera is not unproblematic as a role model. For, she does resemble the traditional fairytale princess with her flawless beauty.

There is also the issue of ethnicity, with the Teutonic Rohirrim set against the darker-complexioned Freca, Wulf and the Eurasian-like Dunlendings. This is an issue I wish to expand upon in greater detail as part of a later piece I have planned. So I will leave it as simply having been noted here for now.

Among Tolkien fans online, a great deal of noise is made about continuity with onscreen adaptations of his work. That is how any new adaptation fits in with Tolkien’s own books or other screen versions derived from them. This has proved to be contentious with certain points concerning "The Rings of Power" series on Amazon Prime. My own view is that, if, to make it interesting, a storyline results in some overall degree of disharmony, that is not necessarily a problem. However, this film, which is more clearly tied to the original trilogy of films than "Rings of Power," has an uninteresting storyline and thus unnecessarily creates technical issues for those films.

In "The Lord of the Rings," Gandalf places his trust in Saruman once the identity of Bilbo’s ring is made certain. That is, one of the wisest of all beings in Middle Earth has still not understood Saruman’s turn to evil at that stage. Yet, from "The War of the Rohirrim," we are supposed to believe that Hera, a mere mortal from the somewhat obscure realm of Rohan, is not keen to offer her help to Saruman, now a key ally of her homeland, but instead search out Gandalf who is supposedly obsessed himself with rings at this time. This not only implies that Héra somehow anachronistically sees Saruman for what he will become, but it also creates an inconsistency in Gandalf supposedly being preoccupied by rings yet his failing two centuries later to see for ages the significance of Bilbo’s one.

Then there is the issue of the Rohirrim and the Mumakil, or giant pachyderms. In Jackson’s films, at the Battle of the Pelennor Fields, although the intervention of the Rohirrim shakes the Orc attackers of the city of Minath Tirith, the then arrival of the Haradrim and in particular their Mumakil throws the Rohirrim completely off balance. Yet, particularly in warfare, if unfortunately less so elsewhere, human beings learn from the disasters of the past. Thus, "The War of the Rohirrim," by introducing the idea that the Rohirrim have fought Mumak-mounted men before makes the scenes in Jackson’s film inexplicable. For it cannot be that a battle in the former that is so momentous that it causes the fall of Edoras would not be discussed by later generations of Rohirrim, even if Héra’s role in it is forgotten. This would mean that knowledge of how Mûmakil could be defeated in battle should also be known to Theoden and his riders, which is not evident at all in Jackson’s films. Even more strangely, the new film shows that Mumakil and their riders are for some reason easier for the Rohirrim to defeat at their first encounter.

As for the animation, at times it seemed blockish, yet there are some scenes that are rendered extremely well. The snowy scenes actually make the viewer feel cold, and the tunnels under the Hornburg are highly atmospheric. Edoras burning on its hill is also a striking image.

Yet, this still leaves us with the overall problem of this film. As an animation, the figures are by necessity literally drawn two-dimensionally. The sadness is that their characters and the storyline are metaphorically drawn this way too. As such, this film literally expands the onscreen scope of Middle Earth yet effectively adds nothing to the onscreen Tolkien universe. It leads one to wonder why the filmmakers bothered to make it at all. The great pity is that with the latitude they had, a decent and inspiring story could actually have been made from the original Tolkien material.

Review: 1¾ out of 5