© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

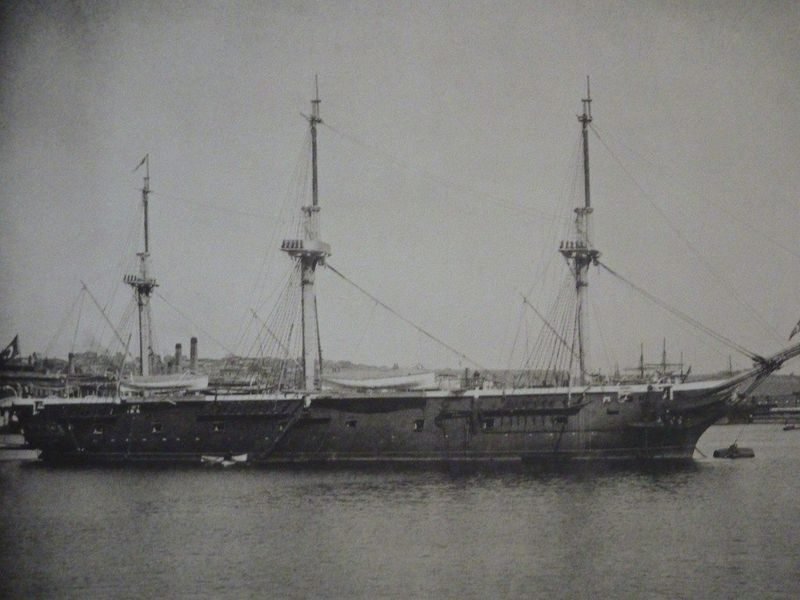

The first relations between the Islamic world and Japan began at the end of the Tokugawa shogunate or the Edo shogunate, the feudal military government of Japan between 1603 and 1868. These relations gained momentum with the reign of Emperor Meiji, also called Meiji the Great or Meiji the Good, in 1868. One of the Muslim states that Japan contacted was the Ottoman Empire. The first official meeting between the two states took place in 1887 with the visit of Prince Komatsu Akihito from the Imperial Family of Japan to Istanbul. A delegation was organized two years later upon Sultan Abdülhamid's request for a return visit to the country. The delegation got on board the Ertuğrul Frigate in July 1889 and left Istanbul for Japan.

Visiting various countries, the frigate arrived in Japan’s Yokohama in June 1890 after a slight delay. The fleet commander Osman Pasha presented a letter sent by Sultan Abdülhamid, the order of privilege and gifts to the Japanese emperor. The delegation, which held meetings in Japan for three months, set off from Yokohama on Sept. 15 to return to Istanbul. However, while on the way to Kobe the next day, the Ertuğrul Frigate encountered bad weather, crashed into rocks and sunk.

The Ertuğrul disaster made such an overwhelming impression in the Japanese press that newspapers covered various articles on it. The newspapers also launched aid campaigns for the 69 survivors of the frigate. This was the first campaign held for foreign survivors in Japan. Jiji Shinpo, one of the largest newspapers in the country, collected the most aid, with a total of 4,248,976 Japanese yen.

It was decided that the survivors would be sent back to Istanbul on two Japanese warships called Hiei and Kongo. The money collected for the frigate survivors would be delivered to the Ottoman government in this way as well. Shotaro Noda, who worked at Jiji Shinpo, was chosen for this important task. Noda was born into a Samurai family in 1868 and came to Tokyo to study in 1886. After his graduation, he started to work for Jiji Shinpo.

Noda immediately went to Kobe, where the survivors were gathered, and the ships departed on the morning of Oct. 11. A large crowd gathered to see Noda when he finally arrived in Istanbul and came to meet the Naval Minister Hasan Pasha on Jan. 6. He delivered all the aid money amounting to 88,497 kuruş (Ottoman-era piaster) to Rıza Hasan Pasha, the head of the aid society established for the victims. The incident appeared in all the Istanbul newspapers the next day.

While he was in Istanbul, Noda continued to write articles for his newspaper. He gave interviews to European and local newspapers as he attracted a lot of attention as a Japanese citizen. When the Japanese ships were to leave for Japan, Sultan Abdülhamid wanted a Japanese officer to stay in Istanbul to both learn Turkish and to teach Japanese to Ottoman officers. Upon this request, it was decided that the journalist Noda should remain instead of an officer, which the Ottoman government also approved.

Thus, Noda, who was awarded a third-degree privilege medal, began teaching Japanese to two officers and six students from the Ottoman Military Academy. The officers also taught him Turkish. His students learned Japanese in a very short time. In fact, one of the students, Mustafa Asım Efendi, even prepared a Turkish-Japanese-French trilingual dictionary.

Noda acted as a translator for Kiyoura Keigo, the future prime minister who came to Istanbul during his stay. He also acted as an interpreter for the businessperson Yamada Torajiro. Yamada organized another aid campaign in Japan, and he probably came to Istanbul in April with the intention of delivering the money he collected. He went to the mansion of Foreign Minister Sait Pasha to meet him, and Noda was called when the pasha needed an interpreter to communicate with Yamada. Noda and Yamada met on this occasion.

Trying to establish commercial relations between the Ottoman Empire and Japan, Yamada also helped Noda in his Japanese lessons. He then returned to Japan in July 1892. After staying in his country for one more year, he would return to Istanbul and open a shop selling Japanese goods in the historical Pera district. He would stay in the Ottoman Empire for about 10 years and return to Japan after the start of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905.

Noda, who taught at the Ottoman Military Academy for about two years between 1891 and 1892, studied the history of Islam and the Ottoman Empire. He read books about Islam and gathered information about the religion. Affected by the good treatment shown to him, he converted to Islam on May 21, 1891, took the name Abdülhalim and was circumcised. Thus, he went down in history as the first known Japanese Muslim. Noda's conversion to Islam was welcomed in Istanbul, and his photographs were published in Ottoman newspapers.

Noda, who probably started to feel homesick after Yamada's departure, left Turkey at the end of 1892. He returned to Tokyo via Europe and the United States. The journalist wrote a letter to Sultan Albdülhamid on Feb. 5, 1893, and thanked him for the Turkish lessons he took. Continuing his journalism career in Japan, Noda died at a young age on April 27, 1904.