© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

The French naval officer and novelist Pierre Loti (1850-1923) is probably the most famous of all travelers to Türkiye as a traveler to Türkiye per se. By which I mean there have been other travelers more famous than Loti who visited Türkiye, such as within this series, Alexander Pushkin, or outside of, Winston Churchill, but with these figures, their fame is relatively or almost totally incidental to their visit. The fame of Loti, however, is inextricably connected to his visits to Türkiye and thus he clearly merits a place in this series. It is also apt that one part of the city of Istanbul immortalizes his name and that it is one of the most beautiful spots in the whole megalopolis.

Lesley Blanch, herself a formidable traveler and writer produced a highly readable biography of Loti. Within it, she affirms the French novelist that:

"No stranger has understood and savored the city of the Sultans better than Loti. Just as every historic city about the world has its quintessential moment in time (the geography of time), so it has its painter or writer who interprets it best: Turgenev for Russia with its endless birch forests: Dickens and Cruickshank for London with its foggy streets, snug pubs and pork pies. Constantinople finds its most perfect expression through Loti’s eyes, as he found it his perfect subject."

It must be noted that Blanch’s unconscious Eurocentricism is revealed in this passage for each of her perfect “interpreters” save for Loti are natives of the countries they interpret. Nevertheless, Blanch’s assertion is significant in that it reveals something of the power of Loti’s writing. It is highly atmospheric, and Henry James, a contemporary of Loti who surely ranks among the greatest writers of that age, has this to say of him:

"Loti performs so beautifully as to kick up a fine golden dust over the question of what he contains and what he does not ...The whole second-rate element in Loti becomes an absolute stain, if we think much about it. But practically (and this is his first-rate triumph), we don’t think much about it."

James is right in noting there is much in Loti’s writing that is unremarkable. His storylines are so highly simplistic that they resemble those of the opera. Yet, his novels are also operatic in their high emotional tragic tone and it is this fact and Loti’s facility with description that obscures all else with James’ “golden dust.” Loti’s way of writing is evident from his first novel, "Aziyade," which, like most of his other work, is highly autobiographical.

Aziyade was written in the wake of Loti’s first trip to Türkiye in 1876. Before, examining that visit though, I would like to give a short summary of Loti’s early life. Pierre Loti is the pen name of Julien Viaud who was born to a well-to-do family of Huguenots in 1850. In Loti’s youth, slander against his father caused a fall in the family’s fortunes and initiated a constant fear of descending further into destitution, until that is, Loti found success as a writer. Loti had an elder brother whom he idolized and who became a surgeon in the French navy but who died young and was buried at sea in the tropics. Loti was inspired by his brother to join the navy himself and in a major early voyage he sailed to Tahiti, a trip which would help establish the romantic myth around himself.

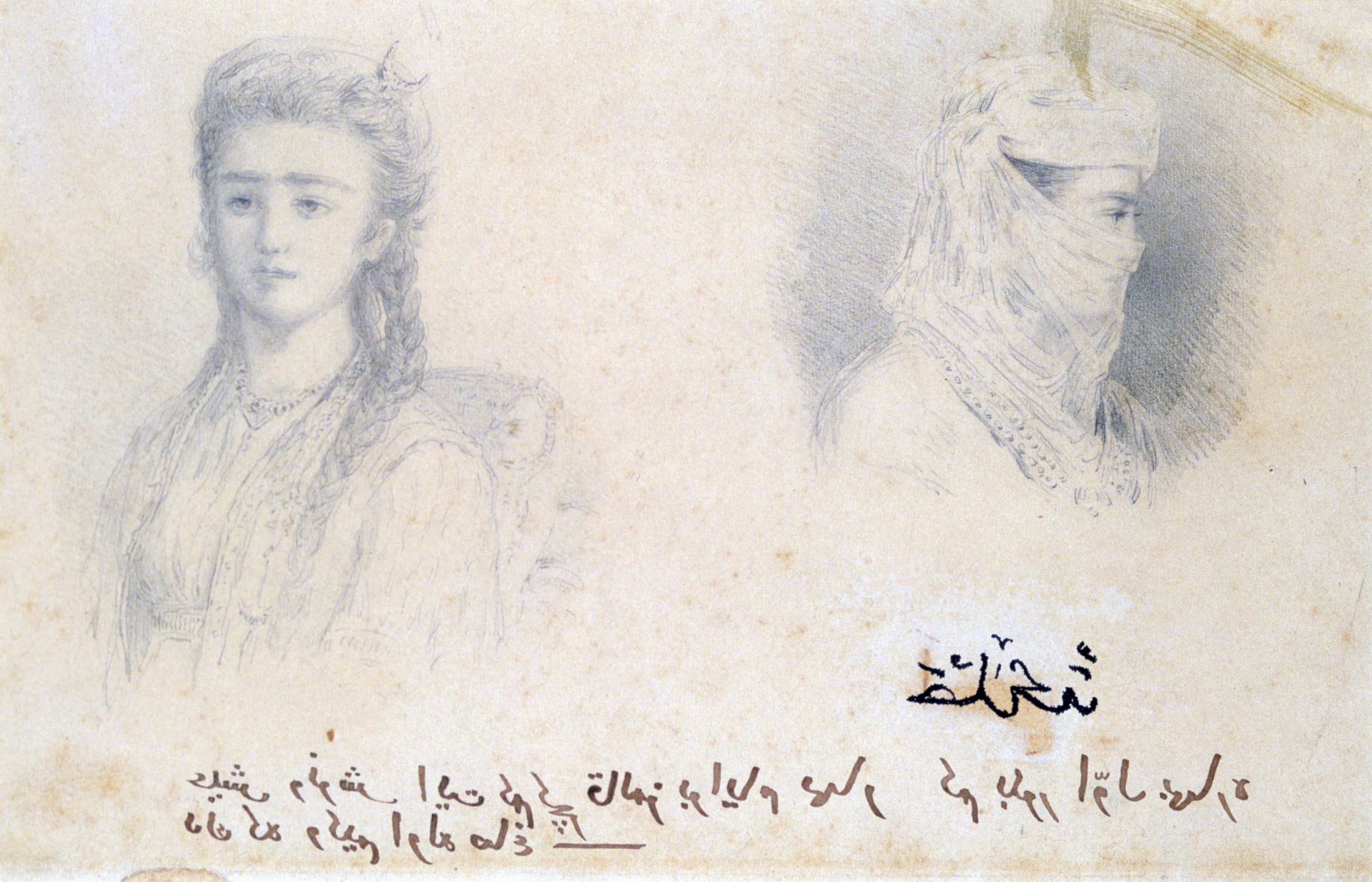

In 1876, Loti’s ship brought him to Salonica, then still part of the Ottoman Empire, and one of its major cities. It is in Salonica that Loti falls in love in two different yet interconnected ways. Firstly, in the narrow streets of that city, he suddenly sees from a house a pair of “great green eyes intent upon my own.” They belong to Hatice the young Circassian fourth wife of the aged Abidin Effendi though she was to be immortalized in fiction as "Aziyade" and it is by that name that she will be known for the rest of this piece. Loti contrives to arrange a meeting with Aziyade in which he is so deeply smitten by her that he calls it “madness.” Secondly, he falls in love with Türkiye itself, a feeling that becomes more profound when he moves from Salonica to Istanbul. As will be seen, these two loves of Loti play out in differing ways.

Loti, smitten with Aziyade, is told by her that she too will come to Istanbul later in the year. As a fantasist, Loti wishes to live the life of an Ottoman and so he creates an alternate persona – that of Arif Ussam Effendi, a supposed Albanian, this nationality is cleverly chosen to explain Loti’s poor grasp of Turkish. He also opted to live in what was certainly one of the most Turkish parts of the city, the neighborhood surrounding the Eyüp Mosque. Indeed, Loti was present when Abdulhamid II was girded with the sword of Osman there. While awaiting Aziyade, Loti forms a companionship with a local man, Ahmet, who shows him around the city. What he seemingly most wishes for save for Aziyade’s presence is to separate himself from his Western European background as he makes a conscious decision to keep apart from his crewmates.

Aziyade is finally brought to the city in December, and Loti is now able to converse with her as he has been studying Turkish in the meantime. His idyll with Aziyade is intense and leaves a marked impression on Loti for the rest of his life. However, it is relatively short as Loti learns that his ship is to depart in the middle of March. He attempts to prevent leaving with it, but failing to do so through acceptable channels, he does not attempt anything radical such as desertion, though as Blanch notes it would have been “easy” for him to “vanish into the Turkish scene forever.” Yet, he only enjoys being Arif Ussam as an alter ego, not as a permanent personality, and he feels a strong sense of duty to his family back in France and to the French navy.

Aziyade, however, deeply in love with Loti, does not find this bitter pill as acceptable to swallow as Loti does. Indeed, she suffers something of an emotional break on their last night together, even attempting suicide by trying to cut her wrist with the shard of a coffee cup.

The next day, Loti, once more in his French naval regalia, is actually accompanied by Aziyade to where he is to embark on his ship. As Blanch notes “the risks she ran, as a veiled Turkish woman beside a giaour were of no further matter to her now.” As he is about to board the landing craft that will take him to his ship, a carriage appears into which she enters and is driven away. The two lovers will never see each other again.

However, Loti has created a system by which the two are able to communicate through letters, and the following year, Aziyade sends a letter to Loti in which she reveals that she is in a desperate situation. Married to the much older Abidin Effendi, she seems to have lived in the hope that in the not-too-distant future, she would be widowed and thus free to marry the man she truly loved. However, she tells Loti that Abidin Effendi is going off to war but should he not return there is a much younger suitor named Osman Effendi waiting in the wings, who could permanently separate them.

Although this letter deeply distresses Loti, he replies to Aziyade advising her to remain by Abidin Effendi should he live, but to actually marry Osman Effendi, should he die. He adds a whole plethora of arguments as to why a life in Istanbul with Osman Effendi would be preferable to a life in France with himself. These of course speciously conceal Loti’s true motivation. Blanch notes here that despite Loti’s manifest Turcophilia and his dreams of Aziyade, as far as France was concerned “he did not envisage her there in the flesh” as he could not imagine “a Circassian odalisque as daughter-in-law for his venerated mother” or “among the bourgeois French wives of his naval colleagues.”

What Aziyade would make of this cold-hearted reply is easy to guess. Blanch rightly points out she “would realize that, in spite of all the protestations of love, Loti no longer had any place for her in his life.” He had used her. However, it may be that she never received the reply as unbeknownst to him, an unexpected death had caused a break in Loti’s secret postal system.

Once the real connection to Aziyade is severed for good, though, Loti becomes free to safely indulge in an obsession about her. As Blanch notes, “Now began the cult of Aziyade the loved and lost, Aziyade the loved above all others.”

On a return trip to Türkiye in 1887, he learns the fate of his former lover from the wife of Ahmet. She tells Loti that “it was about three years after you left” that “they took her away one evening, almost stealthily ... though old Abidin her master ordered a tombstone for her.” Brought to her tomb by the slave woman who had once acted as the lovers’ go-between, Loti is castigated there by this woman for having caused Aziyade’s death.

Yet Loti finds a way to salve his conscience towards Aziyade. He returns to the tomb in the rain and throws himself upon it. Then, however, he feels, as he puts it, “an exquisite illusion that Aziyade’s phantom was beside me, that she knew I had returned, and she understood everything ...Then all the bitterness and remorse which clung round my memories of her vanished forever.”

This did not mark the end of Loti’s association with either Aziyade or Türkiye, though. He later managed to get this tombstone brought to his home in France where it can still be viewed today as part of what is called his “mosque” or the room that houses the Turkish relics in the former house of Loti’s in Rochefort which is now a museum.

The slightly fictionalized version of Loti’s relationship with Aziyade launched his career as a writer with the 1877 novel "Aziyade." He would go on to publish numerous books and his standing as a writer in his lifetime is most clearly demonstrated by his election to the prestigious Academie Française in 1891. Here, however, I would like to examine Loti’s continuing deep affection and support for Türkiye as that country went through arguably the most difficult and humiliating period of its existence as it entered the 20th century.

On Loti’s love for Türkiye, Blanch has this to say, stretching right back to his first visit in 1876:

"From the moment he reached Turkish waters, he was identifying with Turkey, its ways and its people so that already he resented European condemnation over the thorny question of Christian minorities. Loti was never a political animal. He saw each country subjectively, as it affected himself. In Turkey he had found a people, a woman, a mystic faith, a land and its art, all surpassing anything he had known before. For the rest of his life he was to remain under the spell, blindingly loyal."

Although Loti had established himself as a writer of personalized fiction, in the second decade of the 20th century, Loti took up his pen in defense of the country he loved so much and of which he watched, horrified, as greedy parvenu European states started to dismember it. He thus wrote angrily against the annexation of Libya by Italy in 1911 with worse to come the next year when the independent Balkan states briefly united to drive the Ottomans almost completely out of Europe, a continent in which they had been established for centuries.

As Blanch notes, “Loti felt Turkey’s anguish as his own and was lacerated, humiliated and helpless.” But his pen was still a mighty weapon and he wielded it against the French prejudice that favoured the Christian states. Eventually, the powers of the French state, wishing France to remain neutral, effectively had Loti silenced. Loti’s attitude also meant that despite his fame, he was regarded with suspicion in his hometown. Yet the apogee of his personal trauma was to occur the next year when the two countries that meant so much to him, France and the Ottoman Empire, wound up on opposite sides in World War I. He even sought, though failed, to find a way to bring about peace between the two.

Moreover, his agony was not assuaged at the resumption of peace because, as Blanch notes, “he had foreseen the Allied terms imposed on a defeated Türkiye would be very harsh” despite the fact that “they were even more severe than he had believed.” That this definitely affected Loti personally is clear from his revelation that “I have suffered much these last months, seeing the infamous machinations against my beloved Türkiye.” Having suffered a stroke in 1921, Loti was even visited by a delegation from the newly emerging Türkiye, who wished to thank him for his constant support. Two years later, in 1923, the birth year of the new republic, the greatest of all French Turcophiles breathed his last. Aziyade is known to have still been on his mind well into the final part of his long and fascinating life.

Thus ends this sketch of the dual lover, and it reflects the mixed feelings I have toward Loti. On the one hand, I cannot but help find his treatment of Aziyade to have been callously selfish. Even in rereading what I already knew in order to prepare this piece, I became quite emotional at Loti’s treatment of Aziyade. It is true that both Loti and Aziyade commenced a relationship in a society that took its religious and cultural mores incredibly seriously, and perhaps Aziyade understood the implications of this better than Loti did. Yet in spite of this, it is impossible for me, at least, not to view Aziyade as a victim in that it is Loti who abandons her and then later refuses to assist her despite her pleas.

While on Loti’s side, the whole story of Aziyade provides him with material with which to begin his career as a feted writer, on Aziyade’s side, his abandonment of her causes her death. These stark facts make a strong case against Loti. It is the slave woman at Aziyade’s grave who tells him the truth, not his imaginary specter of his former lover.

Nevertheless, his inconstancy toward Aziyade is counterbalanced by a loyalty to Aziyade’s country, a loyalty that did not waver despite it taxing Loti’s own existence. When the Turkish delegation comes to visit him toward the end of his life, this is not a phantasm self-created to soothe a troubled conscience like that of Aziyade but a concrete recognition on the part of the Turks of the constant support that they have received from their famous foreign friend. Moreover, although Loti failed Aziyade in life, he seems to have remained constant to her in death, though whether that really means that much, I leave it to the reader to decide.