© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

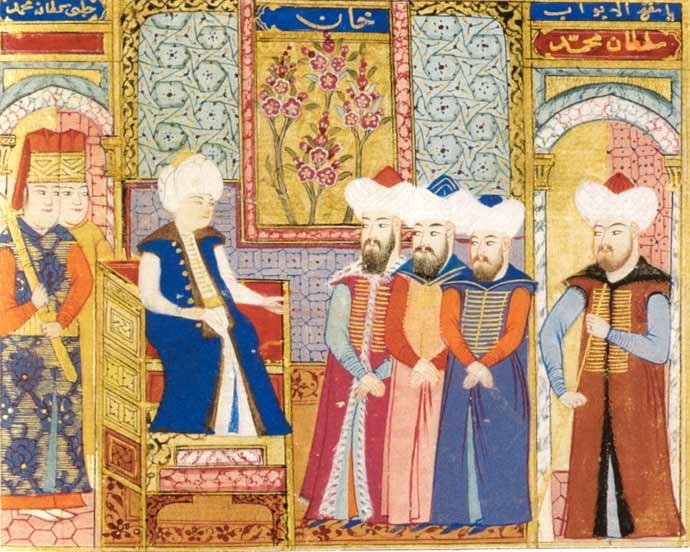

After the reign of Sultan Bayezid, also known as Bayezid the Thunderbolt, Sultan Mehmed I ascended to the Ottoman throne. Sultan Mehmed I was also known as Mehmed Çelebi, a Turkish title meaning "gentleman," "well-mannered" or "courteous." Mehmed I brought order and peace to the country that was in great disorder after the Timurid invasion and became the second founder of the Ottoman state by pulling his father's legacy back together. As he was a master archer, he was also called “kirişçi” (kiriş means bow in Turkish). Mehmed I even shot the Mongolian commander who came to take him as a hostage during the Battle of Ankara with an arrow. It is also said the title of “kirişçi” comes from the Greek word “krytsez,” meaning "little bey (sir)."

The date of birth of Sultan Mehmed I is not certain, but he was likely born in 1382, 1386 or 1389. His mother, the Germiyanid princess Devlet Hatun, was also called by the title of “Çelebi” because she was a granddaughter of the great Sufi mystic Mevlana Jalaladdin Rumi. This title was also given to the descendants of Rumi. Thus, the lineage of the Ottoman dynasty goes back to Caliph Abu Bakr and Caliph Omar, the companions of Prophet Muhammad and also to the prophet through his grandson Hussein, and finally to the tribe of Quraysh.

He was educated by the famous scholars of the time when he was a şehzade (prince) and was assigned to Amasya as the governor to the Eyalet (province) of Rum. He participated in the Battle of Ankara, waged against Emir Timur (Tamerlane) sultanate, at the age of 16 and was wounded. After the Ottomans lost the war, he wanted to save his army and withdrew to his eyalet. The people of Amasya opened their doors to him. Şehzade Mehmed attempted to rescue his father from captivity following this battle, but he could not succeed.

Upon the death of his father, his elder brother Süleyman Çelebi proclaimed his sultanate in the capital Edirne, while Isa Çelebi did the same in the former capital Bursa and Musa Çelebi declared that he ascended to the throne in Kütahya. Thus, the remaining Ottoman country was divided into four, which was exactly what Timur wanted. All four brothers acted diplomatically and declared their allegiance to Timur. Thus, they were able to impose their authority on the local beys who were under the suzerainty of Timur. None of the Balkan states thought to benefit from this turmoil.

An interregnum period then began in Ottoman history, in which the şehzades struggled for about 10 years. Ottoman historians do not accept the rule of the other three children of Sultan Bayezid, as the succeeding sultans were descended from Sultan Mehmed I. The three brothers of Sultan Mehmed I were never able to dominate the entire Ottoman country. But European historians and some modern Turkish historians count Süleyman and Musa on their list of sultans because they ruled in the capital city of Edirne, and show Mehmed and Isa to be subordinate to Süleyman.

Since there was no primogeniture rule or an established rule of succession for the Ottomans, the elder had no superiority over his other brothers for the throne. In the old Turkish tradition, power was considered the common property of the dynasty. Therefore, the brothers cannot be accused of being ambitious because they did not leave the throne to the others. Isa Çelebi, who did not consent to Mehmed Çelebi's offer to share the lands in Anatolia, was provoked by Süleyman Çelebi. He then was defeated twice, one after the other, and killed by Mehmed Çelebi in 1410. Thus, a large part of the Ottoman lands in Anatolia passed to the rule of Sultan Mehmed.

Mehmed then defeated Süleyman who was advancing on him by collaborating with his brother Musa in 1411. Süleyman was caught unaware and killed by some villagers on his way to Istanbul when Musa entered Edirne freely. He was described to have a good heart but was a self-indulgent person.

Then Musa did not keep his promise of obedience to Mehmed and declared his sultanate in Edirne and besieged Istanbul. Meanwhile, Mehmed came to Istanbul and made an agreement with the Byzantine emperor and secured himself there safely. He was the only sultan who came to Istanbul before Sultan Mehmed II, also known as Mehmed the Conqueror.

The suppression of Musa (1413) by Mehmed was quite troublesome. But the Ottoman commanders and people preferred a moderate Mehmed instead of a harsh Musa. Musa, who was defeated in Inceğiz near Istanbul, was executed. Thus, Sultan Mehmed Çelebi became the sole ruler of the country. He declared that he wanted to live in peace with all his neighbors.

The Ottomans were subjected to Timur's son Shah Rukh on paper, and Shah Rukh was not satisfied with the reestablishment of the Anatolian union. He wrote a letter of reproach to Sultan Mehmed on the grounds that it was against the customs of Genghis Khan – the founder and first great khan of the Mongol Empire – that he eliminated his brothers. Sultan Mehmed I, who was very careful not to stir up trouble with Shah Rukh, replied: "My ancestors have solved some difficulties with experience. Two sultans cannot live in one country.”

After that, Sultan Mehmed started to work to restore the unity of the country. He had the genius of his father but was much more moderate. He succeeded in improving relations with the Mamluks, which had deteriorated during the reign of his father.

While Sultan Mehmed I had been struggling with his brother Musa, Mehmed Bey II of the Karamanids entered the Ottoman lands and besieged Bursa. At that time, the funeral procession of Musa Çelebi came to the city. Thinking that the Ottoman army was also coming, Mehmed Bey prepared to flee, setting fire to the grave of his maternal uncle Sultan Bayezid outside the city. One of his officers said to him: “This is how you run away from the corpse of an Osmanoğlu (sons of Osman). What would you do if he came alive?"

Thereupon Sultan Mehmed I advanced on Anatolia and added beyliks (principalities) of Aydınids, Menteshe and Sarukhanids, which his father had conquered and Timur gave back to their former beys, to the Ottoman lands once again. The Isfendiyarids declared allegiance. But these beyliks made an alliance with Karamanids against the Ottomans. Cüneyd Bey of Aydınids, whom Sultan Mehmed had forgiven and assigned as the governor in Rumelia, broke his promise and set up a conspiracy against the sultan. Meanwhile, the Genoese, who dominated the Aegean islands, declared their alliance to the Ottomans in return for taxes.

Then Sultan Mehmed I defeated Mehmed Bey II of the Karamanids, who was his aunt’s son. As Mehmed II fled, half of his territory fell into the hands of the Ottomans. The son of Mehmed II of Karamanids swore on his father's behalf, saying: "As long as this soul is in this body, we will not draw a sword against the Ottomans again." However, when the sultan left, he released a dove that he had hidden in his jacket and declared that his oath was void. He said to those around him, "Our enmity with Osmanoğlu will continue from the cradle to the grave."

Sultan Mehmed I, who more or less succeeded in establishing a union in Anatolia, later moved to Rumelia. He advanced on the Venetians, who violated the treaty of 1414 with the Ottomans. The Ottoman navy of 30 ships, which was not as familiar with the techniques of naval warfare as its enemy, was defeated. But the Ottomans continued to harass the enemy on the Aegean islands through hit and run tactics. Peace was made between the two powers through the mediation of the Byzantine emperor, and Venice compensated for the damage it caused. The Ottomans also granted Venetian merchant ships the right of passage through the Dardanelles. An Ottoman ambassador took the certified copy of the agreement to Venice and was greeted with a festive ceremony. This was the first Ottoman ambassador to Europe.

Sultan Mehmed I later advanced on Wallachia, which stopped the symbolic tax it had paid for a long time and was undergoing a struggle for the throne. The Hungarian-Wallachian allied forces were defeated, and the Ottoman domination over Wallachia was confirmed. The southern part of Bosnia and Albania fell into the hands of the Ottomans. Bosnians and Albanians, who belonged to the Bogomil sect of Christianity – which is close to Islam – were fed up with the Catholic propaganda of the Hungarians, and began to convert to Islam en masse.

The most important event of this period is the rebellion of Sheikh Bedreddin, son of Musa Çelebi's kazasker (chief judge) in Simavna (Kyprinos). When Musa Çelebi was defeated, Sheikh Bedreddin was made to reside in Iznik with a salary of 1,000 akçe (the chief monetary unit of the Ottoman Empire, also known as silver piastres). The proud and ambitious sheikh resented the exile and adopted an opposing stance to the sultan. One of his disciples, Börklüce Mustafa, rebelled with 5,000 people in the Karaburun Peninsula close to Izmir. Torlak Kemal followed him in Manisa with 3,000 men. Both revolts were suppressed. Realizing that he would be held responsible for the rebellions, Sheikh Bedreddin escaped and took refuge with the prince of Wallachia. He advanced to Edirne with a dissatisfied mass gathered around him. The 200 people sent against him dispersed the sheikh's forces. The sheikh was delivered by his men to the Ottomans, falling into a trap. He was brought before Sultan Mehmed in Serres. Since he was not only a simple revolutionary but also a religious scholar, a trial for him was ordered in the presence of scholars. As a result of the trial, he was found guilty. The sultan demanded that a sheikh would give a verdict about Sheikh Bedreddin. And the sheikh in charge also said that the punishment for this crime was execution. The sheikh, who was wrongly known as a communist because of his disciple Börklüce's contradictory ideas of rejecting private property, was executed in 1420.

When Timur returned to his own domain after the Battle of Ankara, he had taken Şehzade Mustafa, one of the sons of Sultan Bayezid, as a hostage. Mustafa, who was released by Shah Rukh, rebelled in Rumelia in 1420 with the help of the bey of Wallachia and Cüneyd Bey of Aydınids. He declared his sultanate and even coined his own money. Sultan Mehmed advanced on his brother and demanded the return of his other brother, who took refuge in the castle of Salonica (Thessaloniki), then under Byzantine control, after being defeated. The emperor intervened and decided not to release him but hold him hostage. Ottoman historians are of the opinion that he was not a şehzade, but a trickster and a scoundrel, tender-hearted but not courageous.

Sultan Mehmed Çelebi died in Edirne in 1421 from a heart attack or dysentery at the age of 35. During his illness, he said, ‘’Bring my son Murad immediately, I can no longer get up from this bed, the country should not fall into turmoil.’’ These sentences show that he thought about his country and nation even as he was dying.

The death of the sultan was hidden from the public and soldiers for 41 days until his 17-year-old son, Şehzade Murad, the governor of Amasya, came and took the throne. His body was buried in the tomb he had commissioned in Bursa. Known as the Green Tomb, one of the landmarks of Bursa today, this building is one of the most beautiful examples of Ottoman art.

By reconquering most of the lands left by his father, Sultan Mehmed I handed down a country of 870,000 square kilometers (335,908 square miles), which was only 72,000 square kilometers less than the previous borders. He always carried a great burden on him since he was a child. He faced many challenges but beat them all. He had personally participated in 24 battles and received nearly 40 wounds. He spent most of his time battling illness and died without getting enough of his youth. He once said: “No one has suffered the troubles I have suffered since my childhood.”

His aim was not conquest, but peace. In his time, the Ottomans had an opportunity to rest in Anatolia and Rumelia and to heal the wounds of the 10-year civil war. After him, peace reigned in the empire. He made everyone love him by erasing the atmosphere of terror created by his rivals. He was a merciful, extremely gentle knight. He established friendly relations with his viziers and scholars. He assigned Bayezid Pasha, who was his teacher when he was a şehzade, as his vizier when he ascended the throne and did not leave him until his death.

He immortalized his name by having monumental works built in two capital cities of the Ottoman Empire, namely in Bursa and Edirne. He ordered the completion of the "Eski Cami" (Old Mosque), which his brother had commissioned in Edirne. Then, he commissioned a bedesten (a type of covered market) opposite this mosque as a charity. He also made a madrassa and bath built in Merzifon along with a mosque, madrassa and soup kitchen in Bursa. This madrassa named Sultaniye was so popular that hardworking students were asked "Do you wish to be a teacher in Sultaniye Madrassa?"

It became customary to print tughras (a seal or signature of a sultan) on coins during Sultan Mehmed's time. He constantly bestowed charity upon scholars, widows and orphans and gave food to the poor every Friday. He started the custom of sending gifts to the sacred places in the Hijaz, the notables and the poor of this region every year. This custom, called the Surre Procession (surre means money and gifts sent by the ruler to Hejaz), continued until the end of the Ottoman Empire.

He was of great value to scholars and the pursuit of knowledge. He was close to the famous scholar, Sufi master, poet and doctor Şeyhi. During his short reign, some scientific works were dedicated to him. For example, “Ajaib al-Mahluqat,” written by Persian geographer Zakariya al-Qazwini on astronomy, geography, medicine and botany in an encyclopedic style, was translated into Turkish in his name. And the medicine book “Müntehab fi al'Tıb” by Merdani was written in honor of Sultan Mehmed. The sultan promoted science by donating to the authors of these works. He is the first Ottoman sultan known to recite poetry.

Mehmed was described having a pinkish-white complexion, black eyes, black curved eyebrows, a curved nose, an eagle-eyed glance, a thick beard, wide forehead, broad shoulders, a large chest and long arms. He was handsome and well-dressed. Historians agree that he was a religious, fair, brave, valiant and kind person. He treated everyone kindly. Abdurrahman Şeref, the last Ottoman official historian, states that he was a great ruler like Mehmed the Conqueror or Selim I, known as Selim the Grim, but he says that his true worth remained hidden because he lived in a depressing time. Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall likens him to Noah, who saved believers with his ship.

Kumru Şehzade Hanım, the granddaughter of Amasya Bey Şadgeldi Ahmed, was his first wife. His second wife was Emine Hanım, the daughter of Nasreddin Bey of Dulkadir beylik. He had nine sons and nine daughters. All of his sons, except Murad, died during their childhood or youth. His daughters were married to the princes of the Isfendiyarids and Karamanids or to a vizier or a vizier's son.