© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

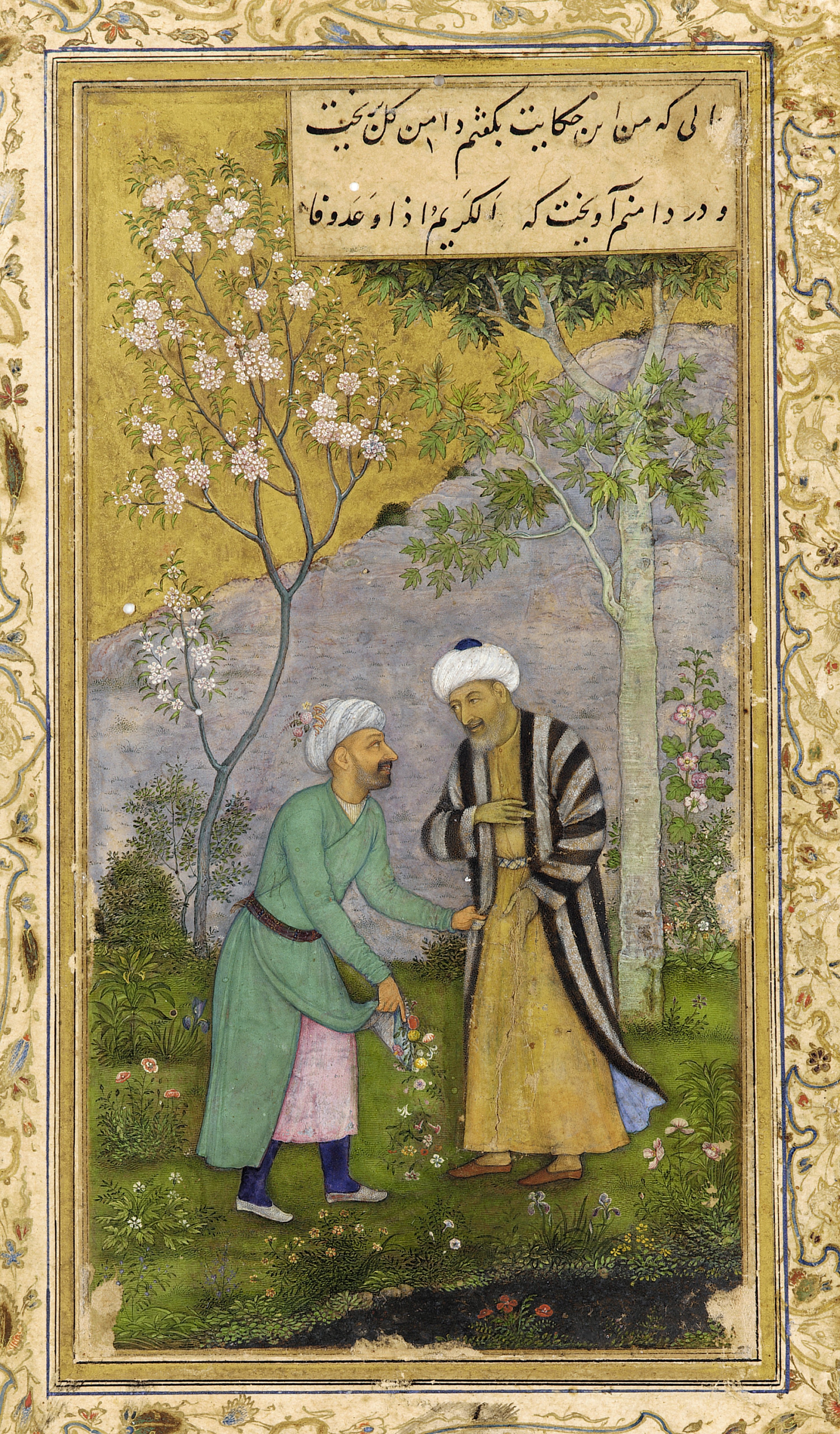

I have asked for indulgences for the last three travelers for the Famous Travelers to Türkiye series. This is the final one and the indulgence I ask for here is the biggest. I wish to close this series with the Persian poet Saadi (c.1210-1291/2), but the truth is that he might not have traveled to Türkiye at all, although if he did, which I intend to show is highly likely, little can be said about what he did here, hence the indulgence.

The facts on the question of whether Saadi ever visited Türkiye are as follows: Firstly, he is the peripatetic poet of Persia. He spent much of his life in travel, as can be seen from the entry on him in the Encyclopedia Iranica, which notes of Saadi that “an extended period of travel around the Islamic world followed his course of studies,” which themselves had taken place in Baghdad the other side of the Zagros Mountains from his native Shiraz. However, this encyclopedia also notes that, “Since there are no contemporary external sources to confirm what Saadi’s works tell us of their author’s life before his return to Shiraz, any account of these years is necessarily tentative,” and as such any “effort to recreate an exact itinerary of his travels from his work is misguided.” It also reveals that “it is probable that Saadi visited Iraq, Syria, Palestine and the Arabian Peninsula, but unlikely that he ever traveled east to Khorasan, India or Kashgar.” It is striking that Anatolia is not even mentioned here.

Nevertheless, an expert on Persian literature, Ahmad Tamimdari, also notes the doubts concerning Saadi’s supposed eastern journeys but clearly states of Saadi that after Baghdad, “he started his famous tours of Hejaz, Syria and Rum,” Rum is the medieval term for Anatolia. And R. Furon, a Western expert on Iranian history, has Saadi undertaking some very great travels, averring that the Persian poet traveled in Asia Minor, East Africa, Turkestan and India as well as numerous places in the Near East, which included 14 pilgrimages to Mecca.

Thus, save for Furon, there is skepticism about Saadi’s possible eastward travels, but they do not interest us here. What is of significance is that the last two of these sources specifically have Saadi in Anatolia. This concurs with what Saadi claims for himself. For toward the beginning of his poetic masterpiece, the Bustan, he declares that, “Much have I roamed throughout the world’s far quarters, spending my days with all and sundry,” but that while away, he kept in mind his native land of Shiraz and thus “from Syria and Byzantium; Yet I was loth, from all those fragrant gardens, to come empty-handed to my friends.” Checking the English translation against the Persian, what has been rendered as “Byzantium” is, in fact, “Rum,” which at this time, as I have already intimated, means Anatolia regardless of whether it is under Byzantine or Turkish rule and in the century Saadi travels, much of Anatolia, and more significantly what of it opens onto the other lands Saadi traveled in, is ruled by Turks.

The reason for any uncertainty concerning Saadi’s travels is that his works are not travelogues and it seems that for some of the places he claims to have visited, he may have used its name for dramatic effect. This is why Furon, who takes Saadi’s words at face value, on the one hand, has a detailed itinerary for Saadi’s travels, whereas the Irancia holds a skeptical view. Yet, there is no dispute that Saadi did travel widely and even if he did sometimes embellish his work, it seems to me extremely unlikely that in the very dedication of one of his most famous books, he would claim to have visited Rum in the full knowledge that he had not.

So, it appears almost certain that Saadi traveled in what is now the Turkish republic. Yet, it is the case that unlike with all the other travelers in this series, whose itineraries I have shown and often in great detail, there is little to say about his visit due to the absence of information on it that has led Irannica not even to mention it. Thus, I need to explain why I chose him as the last traveler in this series. My reasoning is as follows. Most importantly, it rests on the status of Saadi himself. Saadi’s literary status is such that he has been regarded as the Shakespeare of Persia and the expert on Iranian history, Michael Axworthy, notes, “It used to be that teachers of the Persian language used Sa’di’s Golestan to teach their pupils, getting them to memorize excerpts to help them absorb vocabulary and to remember grammar and patterns of usage.”

The simple fact that someone who has had such an influence on Persian literature and language visited what is now Türkiye is, I believe, justification enough for his inclusion. Secondly, he relates a story that almost certainly gives us one place in what is now Türkiye that he did visit. Thirdly, Saadi has been an influential figure in Turkish literature itself. And finally, there is my own bias in that he is my favorite classical Persian poet.

Before dealing with those points, I would like to provide a brief sketch of Saadi’s life. He was born in the Iranian city of Shiraz in the second decade of the turbulent 13th century. His full name is Shaykh Muslih al-Din Abdullah, but he is known by his moniker of Saadi. As a youth, he traveled to Baghdad to study and from there, he later commenced his extensive travels. What causes him to set out on these extensive travels is undoubtedly the same intense desire to learn that brought him to Baghdad in the first place. Saadi exclaims in the Bustan that “did not Saadi travel till he found his desire?” It seems that Saadi was not an intermittent traveler like many in the series; instead, he spent many years away from his home city but made a permanent return.

In the Bustan, he exclaims, “Did you not, when entering Shiraz City, wash your head and body from the dust of travel?” Furon has Saadi back in Shiraz around 1258 in a “splendid dwelling” that is pregnant with the scent of roses and the sound of the nightingale. Saadi remained here, writing his works, until he died in 1291 or 1292. The tomb in which Saadi was buried has drawn many visitors, including Eugene Flandin, who has left a drawing of it. Saadi’s best-known work comprises two books. “The Bustan” (meaning “the Orchard”) and the “Golestan” (which means “the Garden of Roses”), the former of which is a poem and the latter a work in prose, though they share similar concerns.

In the “Golestan,” Saadi makes mention of a significant region in what is now southeastern Türkiye. He relates that “in the territory of Diarbekr (Diyarbakır), or Mesopotamia, I was the guest of an old man, who was very rich and had a handsome son. One night, he told a story.” The story itself will be looked at below. Here, I want to stress that there is good reason to assume that Saadi does have direct knowledge of this place, even if it is allowed that he sometimes embellishes his tales. The reason is that there is no dispute that Saadi did travel in what is known as the Fertile Crescent. He relates in the Bustan that “Fate from Iraq to Syria transported me.” In doing so, he would almost certainly have passed through the northern edge of the Fertile Crescent, which is now part of Türkiye. Ibn Jubayr, from al-Anadalus, who traveled in those Middle Eastern parts of the Arab world that Saadi also traveled in only approximately 50 years earlier, journeyed from Baghdad to Damascus, taking in what are now the Turkish cities of Nusaybin and Harran, both of which are just to the south of Diyarbakır. Saadi must have followed roughly in his footsteps. Although such a curved route may make no sense about the proverbial flight of the crow, the reason that Ibn Jubayr went this way is to skirt the inhospitable desert that lies between Iraq and Syria, which Saadi indeed would not have wished to plunge through either. Hence, I believe that we can take Saadi’s claim concerning Diyarbakır as referencing an actual visit.

As for the story that Saadi claims to have heard there, it continues with the man from Diyarbakır relating that “in this valley, a certain tree is a place of pilgrimage, where people go to supplicate their wants” and that “many was the night that I have been sought God at the foot of that tree before he would bestow upon me this boy.” The father’s joy in his son is manifest. However, Saadi adds, “I have heard that the son was also whispering to his companions and saying: How happy I would be if I could discover the site of that tree so that I might pray for the death of my father.” The son finds the father “a tedious old dotard” and has had more than enough of him. Surprisingly, the moral of this story is not aimed at the son, though, and as such, it is actually more impactful. For Saadi censures the father, exclaiming that “many years are passing over thy head, during which you did not visit your father’s tomb” and then rhetorically asks, “What pious oblation didst thou make to the manes of a parent that thou shouldst expect so much from thy son?” The moral being, of course, is that what one desires for oneself, one should do for others.

This story reflects the significance of Saadi. He is a moralist who uses stories and parables to get his reader to question their lives and alter them for the better. This fact helps explain why Saadi, irrespective of his actual travels in what is now Türkiye, has had such a significant impact on this land regarding its literary culture. For Saadi was taught in the madrassas, or religious schools, across the Ottoman Empire and has been translated into Turkish many times, the first translation of the “Golestan” being made by Seyfi Serayi into Kipchak Turkish, and in the Ottoman period, a rendering into Turkish was made in the 15th century by Mahmut Manyasoğu. This version is held in the prestigious old document library in Topkapi Palace today and as such, Saadi has metaphorically traveled to the very heart of the culture of Istanbul. What is perhaps most fascinating of all is the influence that Saadi had on the Turkish poet Mehmet Akif Ersoy, who is best known for devising the National Anthem of Türkiye.

Saadi has been presented here as both a traveler and a moralist; for him, the former surely informs the latter. On his travels, he saw many different people in many different situations, allowing him to make comparisons between them from which moral conclusions are drawn. In the Bustan, Saadi shows how meaningful comparison is in forming a concept of what is right. He avers that “none knows the value of the day of happiness/Until a day befalls to suffer hardship.” Then, he commences to argue that unless one has experienced misfortune, one cannot understand how it affects a person. Thus, a wealthy man cannot understand the struggles of the poor or the man in good health that of someone suffering from an ailment. His argument is similar to the English idiom about walking in another man’s shoes. In developing this argument, his experience as a traveler is drawn upon, for he adds the following:

“What know the Oxus-dwellers of water’s value?

Ask those who are stranded in the sun!

And the Arab who by the Tigris squats –

What cares he for those who’re thirsty in Zarud?”

Saadi would have seen enough differences in the human family on his travels to recognize that what is abundant for one person is taken for granted by them without proper appreciation and it is those who are in need who know its actual value.

Nevertheless, it must be stressed that any connection between travel and morality is far from straightforward. Indeed, it can be plausibly argued that travel could be harmful to the holding of a moral code. The 16th-century French philosopher Michel de Montaigne notes that different places in the world hold different moral values, and thus, what is regarded as “abominable” in one is held “in esteem” in another. Nevertheless, Montaigne is also aware that what we define culturally as morality, we unquestioningly believe to be universal. So travel, with its concomitant observation of different mores, could potentially weaken a person’s moral certainties. Moreover, the best travelers are surely those who accept what they find in foreign lands rather than those who seek to impose or force their values in the places they go as such traveling would seem to fit better with an amoral rather than a moral outlook.

Yet there is another side to this coin, and it is on that side that the name of Saadi is stamped. While the traveler may see many differences on their journeys, they will also thus see that the hardships facing humanity are more widespread than the person who has never ventured outside of their home region could directly know. This, in turn, can engender a sense of tolerance towards human beings in general. The traveler may also come to see behind the multitudinous minor moral differences a common set of values shared by all.

This is what I believe happens with Saadi. And I am certainly not alone in seeing a higher, all-encompassing, tolerant morality in him. For, to return to the question of Saadi’s travels, wherever he did go, he certainly never crossed the Atlantic Ocean. Yet, today, Saadi is in the most fantastic city in the Western Hemisphere – New York. Yet, he is not there to represent the U.S. but instead all of us. One of his poems is in the Hall of the U.N. It is:

“Human beings are members of a whole,

In the creation of one essence and soul.

If one member is afflicted with pain,

Other members uneasy will remain.

If you have no sympathy for human pain,

You cannot retain the name of a human.

This poem has also been rendered as:

The children of Adam are part of a whole,

In creation, being of one essence and soul.

If misfortune afflicts a member with pain,

Other members upset will remain,

If you feel free of fellow human’s pain,

The designation of Adam you cannot claim!”

Saadi preaches a universalist humanist message that I believe developed from his travels, which they took in Anatolia. With this, I finish the last traveler in this series of twenty-three travelers. However, I hope to write one more piece for the series, which I will provide an overview.