© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

It’s an ironic but meaningful fact that a group of the Russian Empire's Muslim subjects helped institutionalize nationalism in Turkey and the Turkish territories within the Russian Empire in the decades before the Turkish republic was established among the ashes of World War I (1914-1918).

Mirsaid Sultan-Galiev, a member of the Bolshevik Party and the architect of the Muslim national communism ideology, was perhaps the most famous of them. Yet, there were many others, too, mainly non-Bolshevik intellectuals such as Yusuf Akçura, Ahmet Ağaoğlu (Ağayev), Zeki Velidi Togan and Ismail Gaspıralı (Gasprinsky), who each made significant contributions to the Turkish nationalist movement in the late Ottoman and early Republican eras. Some, like Akçura and Ağaoğlu, were politicians, while others like Togan were social scientists.

Gaspıralı, on the other hand, helped the Turkish-Muslim awakening in Crimea through his activities in educational institutions and journalism. He was the publisher of the Tercüman periodical, which was the base of Turkish nationalism in Crimea from the late 19th century to the early 20th century.

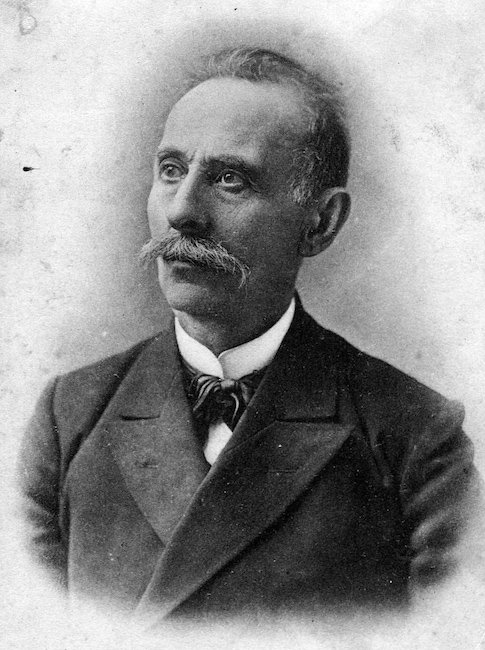

Ismail Gaspıralı was born on March 20, 1851, in the Avcıköy village of Bakhchysarai in central Crimea. His surname Gaspıralı comes from his father’s village Gaspra. His father Mustafa Alioğlu Gasprinsky was a lieutenant who retired from the Russian army while his mother Fatma Sultan was from a notable Crimean Muslim family. Ismail Gaspıralı graduated from the Akmescid Gymnasium for Boys before he was admitted to a military college in Moscow.

Moscow helped Gaspıralı get close to Russian intellectual circles under the influence of pan-Slavist propaganda in those days. He realized the importance of his own ethnic origins as a reaction to that propaganda. He began to search for an awakening of the Muslims within the Russian Empire.

At the same time, he mentally supported the Ottoman Empire. So, he attempted to enter Turkey with a Muslim friend to join the Ottoman army fighting against the Greeks in Crete, but they were captured before crossing the border and dismissed from the Russian military.

Gaspıralı returned to Bakhchysarai and taught Russian to madrasa students. In this period, he read many Russian texts including literary and philosophical works. A few years later in 1872, he traveled to Istanbul, Vienna, Munich, Stuttgart and finally Paris and he made his living by working any odd jobs he could find during the two years he spent in Paris. Gaspıralı even worked as the personal assistant of influential Russian author Ivan Turgenyev. After Paris, he visited Istanbul with a dream to become an Ottoman military officer but wasn’t accepted by the authorities. So, he returned to Crimea.

Gaspıralı was elected deputy mayor of Bakhchysarai in 1878 and mayor in 1879. While serving until 1884, he tried to help awaken the Crimean Tartar Muslims, who in his opinion were asleep politically. In 1881, he began to write his first articles about Muslims’ conditions in the Russian Empire.

The interesting thing was that Gaspıralı had to write in Russian because of colonial rules. He needed a Turkish periodical, which was not allowed by the empire. Until 1883, when he began to publish a Russian-Turkish periodical in Bakhchysarai, he tried to reach the Turkish speaking audience by having small pamphlets printed in Tbilisi, Georgia.

His periodical, Tercüman, carried the name of the famous Turkish newspaper Tercüman-ı Hakikat. Tercüman represented the Tatar renaissance in Crimea for decades. Gaspıralı was the publisher, editor-in-chief, writer and worker during the newspaper's initial period. Sometimes he asked his family for help. Tercüman remained in publication for more than three decades, exceeding Gaspıralı’s lifetime.

In his numerous writings in Tercüman, Gaspıralı propagated the idea he formulated as “unity in language, work and opinion.” He believed that unity and solidarity among Russian Muslims could only be achieved by education. He tried to realize his national education ideal by establishing a private elementary school in Bakhchysarai. Like his work in Tercüman, he did every job in the school, including financing the facility, recruiting teachers, providing materials, writing the program and syllabus and printing the textbooks.

The method he used in the aforementioned private school was called “usul-i cedid,” or “new method of teaching,” which was the keystone of Jadidism, a late 19th and early 20th-century movement to modernize Turkic Islamic cultures within or indirectly influenced by the Russian Empire. Gaspıralı’s method relied on basic teaching of the mother tongue rather than a summarizing of religious rules. He visited many parts of Russia in order to collect support for the new method, which included some notable oil-millionaire families in the Caucasus. At the beginning of World War I, the number of schools teaching with the usul-i cedid method was more than 5,000.

After the Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, Gaspıralı found more freedom to increase the acceleration of his educational and political activities. He was elected as the head of the Council for All-Russia Muslims gathered on Aug. 28, 1905, in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia. He also chaired the All-Crimea Muslims meeting held on Dec. 3, 1905, in Akmescid (Simferopol). These two congresses made it possible to gather the Council for All-World Muslims in Petersburg in 1906. Muslims sent 25 representatives to the Russian assembly Duma thanks to those political activities, in which Gaspıralı played a significant role. In addition, Muslims officially held a congress with the attendance of 800 delegates all around the Russian Empire.

The empire did not wait long to strike back, however, and in 1907 the Russian authority narrowed the limits of the educational and political freedoms of Muslims. Gaspıralı gave an uncompromising reaction to this new policy by trying to hold an international congress for Muslims in Cairo, Egypt. He visited Cairo three times and asked for the Ottoman Empire's support, which he would never get because of the Russian's diplomatic pressure on the weaker Ottoman position. As a result, he could not gather the All-World Muslims congress. Nevertheless, he managed to publish a periodical in Arabic, al-Nahdah, in Cairo.

Gaspıralı visited Bombay (today Mumbai) in order to present his educational method and Jadidism to India, which at the time held the largest Muslim population. Indian Muslims welcomed him and he even opened a sample school in Bombay in order to show the efficiency of his method of teaching.

Gaspıralı had a close connection with the ideological formations in Turkey. All Westernists, nationalists and Islamists respected him and were interested in his method of teaching. Yet at that point, he had been seen as a pioneer by the Turkish nationalists. He was a part of the Türk Derneği (Turkish Association), founded after the 1908 revolution. Every nationalist group and periodical saluted him as one of the keystones of their ideology, which is only partly true.

Ismail Gaspıralı died on Sept. 24, 1914, in Bakhchysarai. More than 6,000 Muslims from all around the Russian Empire attended his funeral. His grave is beside the tomb of Hacı I Giray, the founder of the Crimean Khanate. In 1944, the Soviet administration destroyed his grave during the Deportation of the Crimean Tatars. They returned to Crimea after the Soviet Union collapsed, found the place of Gaspıralı’s grave and built a memorial stone in his name.