© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2025

The North Anatolian Fault runs through the middle of the Turkish province of Çanakkale.

The seismic nature of this province seems to geologically reflect the role it has repeatedly played in human history as the fault line between those most loaded of conceptions – those of east and west. There are two particularly significant examples of this in Turkish history. In the first, in 1354, a physical rupture of the geological fault line led to a shift in the civilizational one. That is because a powerful earthquake that year devastated the Byzantine city of Gallipoli. The Turks took strategic advantage of the situation to take and establish their first permanent city in Europe. The second is the 1915-16 conflict that is known in Turkish as the Battle of Çanakkale but is known in the English-speaking world as the Gallipoli Campaign. It is essential in Turkish history as marking a hard-earned victory against the Allies in the Great War and proving to have been the launching pad for the meteoric rise of the founder of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal, later to be also surnamed Atatürk.

In the English-speaking world, the second of these events is also well-known, especially in Australia and New Zealand, whose sense of nationhood was forged in the fire of this ferocious encounter. The possibility of 1354 is less well known, yet when the troops of Great Britain and its Dominions set out in 1915 to the Çanakkale region, they were not necessarily heading to an unfamiliar part of the world. Indeed, those who had been classically educated would have been aware of its literary associations. That is because of the tale of Troy that was immortalized by Homer in the "Iliad," the fountainhead of European literature, and which is thought to be set around 1200 B.C. in what is now the Asian side of the province of Çanakkale. This tale has been viewed as yet another east-west conflict, but as the term “tale” suggests, it is shrouded in a mist of mythology. According to the legend, a ten-year war was fought around the city of Troy ruled over by the Trojan king Priam and ended with the brutal sack of this Asian city by the European Greeks. This tale had such a powerful hold on the European imagination that epic works suggest the founding of Rome or even far-off Britain was the work of Trojan refugees. All in all, its influence on European literature and art is incalculable.

In 1868, Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890), the third of the travelers to Türkiye in this series, arrived in the country in Çanakkale province, the 1915-16 battle lay unguessed in the far-off future. The German Schliemann, like the second visitor to Türkiye in this series, Dos Passos, was familiar with the "Thousand and One Nights." Nevertheless, it was the "Iliad" that brought him to Türkiye. Before reading Homer relatively late in his adult life, Schliemann claims that he first heard the tale of Troy in a more fairytale-like version. Supposedly, as a young child, he had been given a book containing this tale as a Christmas present. He relates that having been moved by the graphic description of the fall of the city, this seven-year-old boy pondered on its subsequent fate with his father and declared that:

'Father, retorted I if such walls once existed, they cannot possibly have been destroyed: vast ruins of them must remain, but they are hidden away beneath the dust of ages.' He maintained the contrary while I remained firm in my opinion, and at last, we both agreed that I should one day excavate Troy.

If that sounds like a fairytale, it is because it probably is. Schliemann was a man, as his biographer Caroline Moorehead so eloquently puts it, “for whom the truth sometimes appears to be no more than an inconvenience.” There is ample evidence to show that he often made misleading claims. His insecurities also made him one of those who sought to retrospectively endow his life with a sense of mission almost from the outset. However, it is unfortunate that he felt this need because his life, both before and after his decision to become an archaeologist, is fascinating and inspiring.

Having lost his mother while still a child and separated from his father, this driven individual rose through his efforts from being an apprentice in a grocery store to becoming one of the wealthiest people of the nineteenth century. Moreover, it cannot be said that fortune smiled particularly benevolently upon him, much of what luck he did have been made by himself. His life was marked by numerous further hardships and misfortunes, including the loss of one of his daughters, a miserable marriage, and a violent shipwreck.

He was one of those self-made 19th-century energetic men for whom stasis was intolerable. This energy was fundamentally responsible for his meteoric rise in the world of business. Moreover, with this energy, and developed from it initially to assist in his professional ambitions, he developed an intensive method of language learning from which, in a matter of weeks, he was able to obtain mastery of a language. It is thought that he learned 15 languages in his lifetime, including modern and ancient Greek and Turkish.

In his 40s, he then used his energy to burst into the world of archaeology. Yet, despite his manifest achievements, he always felt like a parvenu. To counter this nagging lack of self-confidence, he, as many people in similar situations do, took to aggressive self-promotion and defensiveness. Moorehead reveals that “Schliemann’s boasting could be overwhelming, but there was also something pathetic about it.” Schliemann required his work to reinforce his fragile self-esteem. Thus, although he became an archaeologist, he did not approach this science in a cautious scientific way. Instead, on the sparsest evidence, he would leap to the most grandiose conclusions to maintain his drive and not fall into despair.

It has already been mentioned that the tale of Troy brought Schliemann to Türkiye. Yet, for Schliemann, it was not a mere myth. Schliemann believed that Homer’s account was historically true and he compared it to that of a pious Christian’s faith in the Bible. He declared that his “great goal” was “to prove that the 'Iliad' is founded on facts” and that he would “shun no expense to attain this result.” So, he had come to Türkiye to prove that Homer’s Troy had been a real place. He later claimed that in his first evaluation of possible sites for Troy, he had already understood that Troy was buried under Hisarlık hill. However, it is more probable that a local British resident, Frank Calvert, actually directed his attention to this huge mound. Schliemann certainly sought Calvert’s assistance then and later and was encouraged by him to investigate the part of the mound he owned. Yet, as Moorehead reports “Calvert was to regret his generosity,” and this is because, as the historian, Michael Wood notes, “later Schliemann would deny Calvert’s inspiration and help” as then he was “unwilling to share his glory.”

In the long period he awaited an Ottoman permit to dig, the impatient Schliemann left Türkiye and divorced the Russian wife with whom he had been so unhappy and married a young Greek woman, Sophia Engastromenos. He returned to start digging even without a permit on two different occasions, unsurprisingly, both failed.

It was not until the summer of 1871 that Schliemann finally received his permit, and by the autumn, he was back in Çanakkale province. The permit that the Ottoman authorities granted him obligated him to share his finds equally with a newly-founded museum in Istanbul. Once the excavations began, Schliemann restlessly directed the local workers he had hired. The environment itself was challenging. In addition to the often inclement climatic conditions, there were scorpions, snakes, and malarial mosquitoes. He brutally dug down and down through various layers of history in his impatient effort to reach the earliest Troy. His mood varied according to whether the finds suggested he was nearing his goal. Moreover, he already attempted to force the limited funds he did make confirm to his goal. For instance, early on, having discovered a terracotta bust, he declared that it had the features of Helen of Troy. This first excavation ended without the results he had hoped for. The next year, the dig went much deeper, and more promising finds led Schliemann to impatiently declare that he had found Homeric Troy, though serious skepticism in academic circles was expressed towards him for this.

Indeed, it was not until 1873 that his fortunes changed decisively. That year in unclear circumstances, Schliemann discovered an impressive hoard of treasure, which he hid from his workmen and the Ottoman official assigned to watch over him. Schliemann immediately concluded that this treasure belonged to the Trojan royal house of Priam and had been stashed away as the Greeks assaulted the city. Before the increasingly suspicious Ottoman official could take action against him, Schliemann had this find smuggled out of the country. Moorehead rightly calls this a “wholesale theft.” All that she can find in his defense for this is that he was not alone as a foreign archaeologist in his cavalier disregard for his obligations towards the Ottoman state. With the treasure out of Ottoman domains, Schliemann ended his dig and left the country declaring that “my hopes have been surpassed” and “my mission is fulfilled.” In Greece, where he had sent it, he first adorned his wife in it for one of the most famous photographs in the history of archaeology, before putting it on public display. It would later be gifted by Schliemann to Berlin from where it was confiscated by the Soviets in 1945.

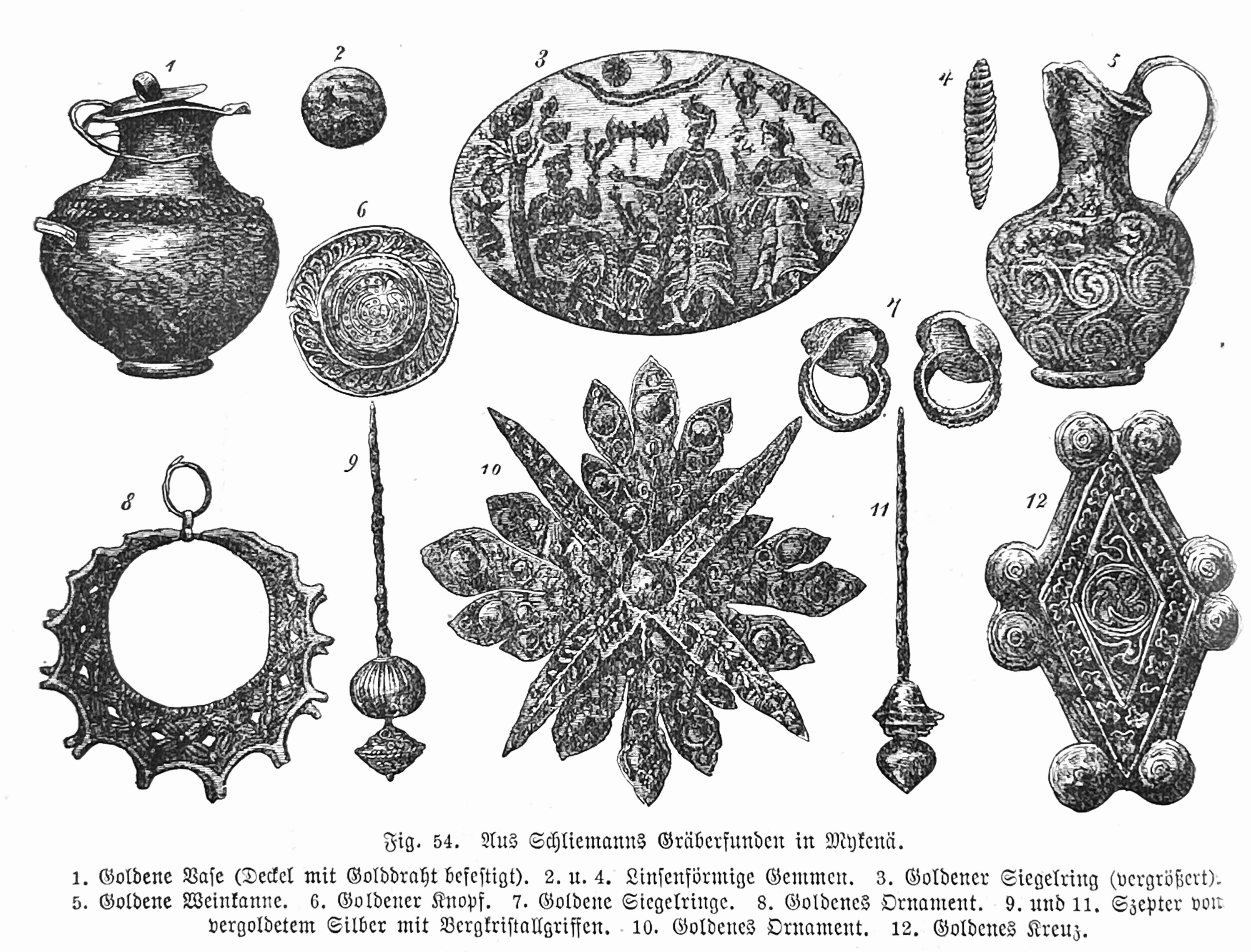

With his treasure, Schliemann became a celebrity. As Wood notes “the find caused a sensation: it was this more than anything that helped Schliemann’s claims to be taken seriously.” His Homeric excavations also did not end at Troy. He conducted digs in Greece at Mycenae and Tiryns. In the former, he once again made a spectacular discovery of previously untouched tombs containing corpses with gold burial masks. Typically though, he was to leap to the conclusion that one of these was the figure of Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek forces in the tale of Troy. He also returned to Troy itself to dig after compensating the Ottoman authorities. He died in Italy in 1890.

Some unanswered questions concerning Schliemann, though, obviously remain. As for the treasure, it is almost certainly too old to have anything to do with the time of the Trojan War. As regards Troy itself, Schliemann did prove that it was inhabited at the supposed time of the tale of Troy, but this does not necessarily mean that anything concerning the Troy of Homer was substantiated.

The picture that has been painted here of Schliemann is a pretty unattractive one. He has been shown to have been a dishonest thieving ingrate braggart. It may seem surprising therefore that I also admire him. I do not, of course, ignore his faults – that is clear from this piece itself. Yet, I, like many others in this current age, find flawed heroes more compelling than flawless ones, and that, ironically perhaps, links the Homeric heroes and Schliemann himself. More importantly, Schliemann’s flaws cannot take away from his self-creation, his drive and tenacity, and his willingness to risk his all in the pursuit of his dream. What is more, he is, at least to me, a figure deserving of sympathy for his being unable to ever overcome his fundamental feeling of worthlessness. Indeed, I hold that it is this human weakness that explains his greatest flaws and thus makes them relatable even though it does not excuse them.

Additionally, Schliemann did provide an invaluable service to our understanding of history by proving that the inhabited history of Troy stretches much further back in history than had ever previously been thought. This with his other excavations, as Moorehead explains, “led to a new chapter in the exploration of the ancient world” and that Schliemann “almost single-handedly ... opened the early pre-Hellenic civilizations to students of antiquity.”

The reader is of course free to disagree with any of these evaluations. But I do hope this piece, if the information contained in it is new to them, might at least add a new dimension to any visit they may make to Troy. It should be said here that superficially, Troy is certainly not one of the most impressive of the ruined cities of the Aegean region of Türkiye to visit. In nearby Pergamon and the more southern site of Ephesus, the remains are considerably grander. Troy, on the other hand, despite all that has been uncovered by Schliemann and his successors, remains very much a ruin. Yet, I regard Troy as the greatest of all the unearthed ancient cities of Türkiye. To appreciate it fully, though, one must make use of the excavated props to construct full theatrical Homeric scenes in the imagination. In this, Schliemann can be a guide.

On his first trip to the site, Schliemann relates that “I imagined seeing before me the fleet, camp, and assemblies of the Greeks ... troops marching to and fro and battling each other in the lowland between city and camp.” One can also imagine seeing down below a hut in which the aged Priam appeals to the slaughterer of his eldest and greatest son to return the body to him for burial – one of the most poignant scenes in the whole canon of European literature. But the visitor of today may also use their imagination to picture a quite different figure from three millennia later. They may picture Schliemann pacing nervously about on the site hoping above hope that in his enthusiasm he had not miscalculated and opened himself up to fail.

For those who prefer some pictorial assistance to see such scenes of ancient myth or modern man, there is a place across the Aegean Sea that can be of assistance. Not far from the most splendid monuments in the Greek capital, there is the First Cemetery of Athens. Should one pass inside and by the heartrending monument to the tens of thousands of Greeks who died of famine in 1940-41 under the German-led Axis occupation of their country, one can find the tomb of a German who brought pride rather than devastation to Greece. It is that of Schliemann and on its sides are carved relief depictions not only of the tale of Troy but of Schliemann’s struggles to uncover the city. Buried with him is Sophia who outlived him by just over 40 years but is immortalized by the photograph of her in the jewelry that her husband had believed had once belonged to the royal house of Priam.