© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

Turkish professor Aziz Sancar is a biochemist who has contributed to mechanistic studies of DNA repair and showed how certain protein molecules correct errors in DNA caused by exposure to ultraviolet light or mutation-inducing chemicals.

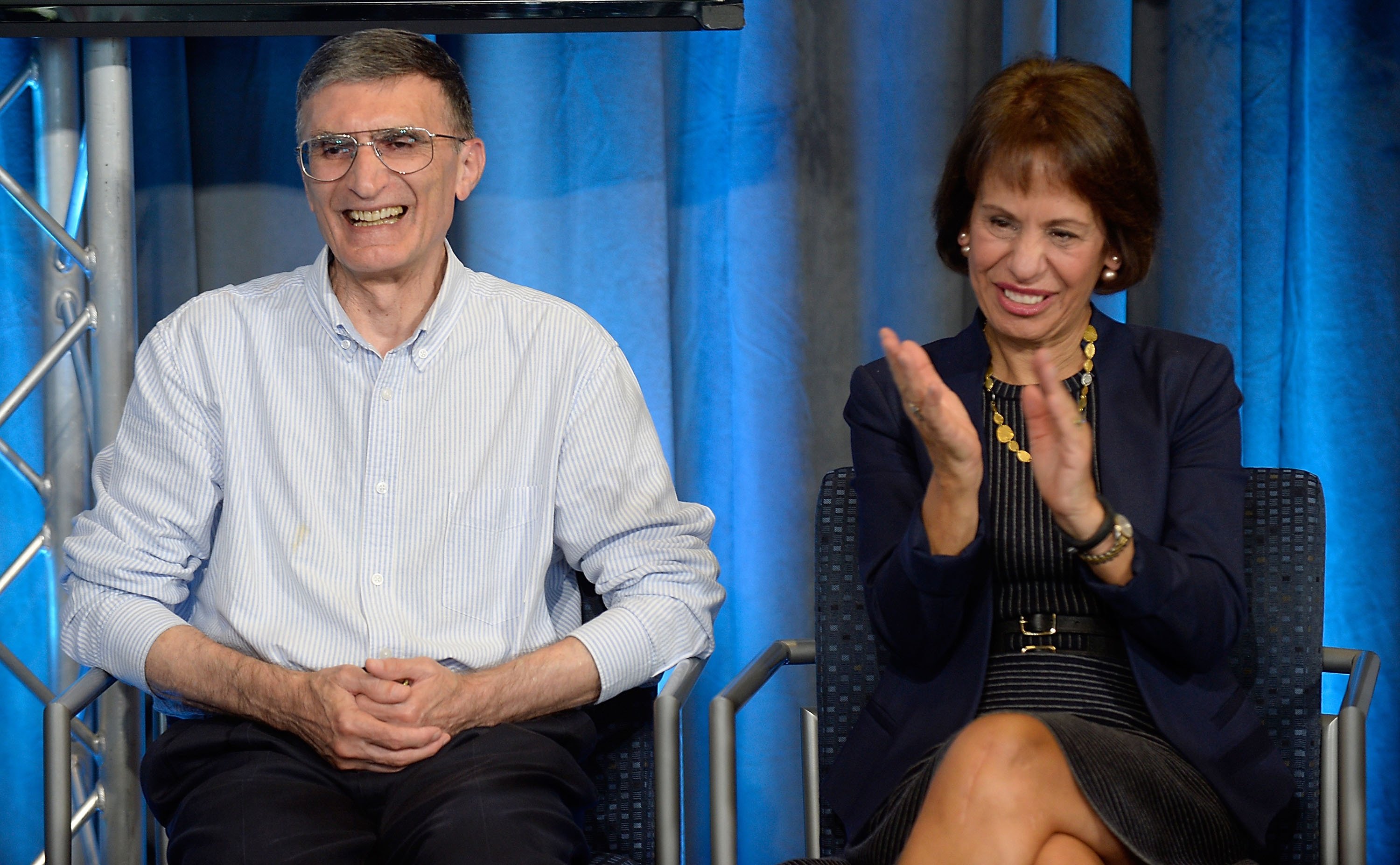

He was awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 2015 along with two other scientists, Tomas Lindahl and Paul Modrich from Sweden. Sancar lives, teaches and continues his studies in biochemistry in the United States, where he moved for his doctoral studies in the early 1970s. He also contributes to the development of science education in Turkey and acts as a goodwill ambassador of Turkish culture.

Aziz Sancar was born on Sept. 8, 1946 in the Savur district of southeastern Mardin province. He was the seventh of eight children of a lower-middle-class family, and his parents were agricultural workers like most of the families in Savur. His father and mother were illiterate but they valued education and did their best to ensure that all their children got the best education they could.

All of Sancar's siblings are university graduates. Two of his elder brothers, Kenan and Tahir, are retired officers of the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) while one of his youngest siblings is a mechanical engineer. Mithat Sancar, one of his second cousins, is a parliamentarian.

As for his ethnic origin, Sancar refuses any other considerations than his being a Turk. “I don’t speak Arabic, nor do I speak Kurdish. They insulted me by asking such questions. I am a Turk and that’s all,” he replied to the press.

Sancar was a hard-working student at school but he also loved to play football. He played as a goalkeeper on the school team, which earned him an invitation to the tryouts of the U-18 national football team when he was in his last year of high school. “This was a dream come true because, since the age of seven, I had wanted to play for the national team,” he said at an interview. “However, upon serious consideration, I decided I wasn’t tall enough to be an outstanding goalie, and instead I concentrated on my studies.”

Sancar was very good at all scientific disciplines during his high school education but he narrowed his choices to chemistry and medicine after graduating. He obtained enough points to get into Istanbul University’s School of Medicine in 1963.

During his second year at the School of Medicine, Sancar decided to become a research biochemist after taking a biochemistry class. However, when he shared his decision with the professor of the class, the professor convinced Sancar to practice as a physician at least for a couple of years. Sancar followed his biochemistry professor’s advice and worked as a rural physician for one and a half years in his hometown Savur after his graduation.

Sancar was committed to moving to the U.S. because, according to his own recollection, “the action was there,” which means that he hoped to be involved in the biochemistry research done in the country. He finally made it to the U.S. in 1973 to join Claud S. Rupert's laboratory at the University of Texas, Dallas. After studying for four years, he earned his Ph.D. in molecular biology and accepted a position as a research assistant at Yale University after three rejected applications for postdoctoral studies from leading DNA repair labs. According to Sancar, he did not receive an offer from these labs as he had not published yet. He had been so engrossed in doing experiments that he had no time to write papers. In 1982, Sancar joined the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, where he later was named the Sarah Graham Kenan Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics.

Sancar got married Gwen Boles Sancar, whom he met at Dallas during his doctoral studies, in 1978. She was also studying molecular biology at the time and is now a professor of biochemistry at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine.

After conducting his early experiments, Sancar visited Turkey in 1976 to complete his four months’ compulsory military service. As previously mentioned, he completed his doctoral study in 1977. During his graduate studies, Sancar, as a part of professor Rupert’s team, was obsessed with the nature of the chromophore of the photolyase, the part of DNA repair enzymes responsible for their coloration. He told his friends that he would give his right arm to be able to identify the chromophore; in other words, how bacteria exposed to deadly amounts of ultraviolet radiation managed to recover. Thus, he made his own experimental research, where he used newly developed DNA technology to overproduce the photolyase and identify the chromophore.

Beginning in the early 1980s, Sancar continued to examine the photolyase in Escherichia coli, also known as E. coli bacteria. After that, he began to explore the DNA damage checkpoints, where he discovered two light-harvesting chromophores in the photolyase, which he proposed were the key components of the photolyase reaction mechanism and its activity at the blue end of the visible light spectrum. In the early 2000s, Sancar finally observed the mechanism of DNA repair by photolyase. He also investigated human photolyase orthologs, where he found that the cryptochromes, located in the eye, function as photoreceptive components of the mammalian circadian clock.

Sancar has continued his studies on DNA repair enzymes since the mid-1970s, which earned him memberships at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (2004), the United States National Academy of Sciences (2005) and the Turkish Academy of Sciences (2005), as well as the Nobel Prize for chemistry (2015). The Swedish Academy awarded Sancar together with Tomas Lindahl and Paul L. Modrich from Sweden for their mechanistic studies of DNA repair.

In his Nobel speech, Sancar mentioned the education reform carried out in Turkey by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish republic, which he identified as the foundation on which he could do his scientific studies. He also submitted the Nobel medal given to him to the Atatürk and War of Independence Museum at Anıtkabir, the Atatürk Mausoleum in the capital Ankara.